You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Alejandro Ramirez-Cisneros, Tufts University

Tufts University will erase the name of major donors, the Sackler family, from all programs and buildings at its Boston medical campus because of the name’s close association with the opioid epidemic, university officials announced Thursday.

The university does not plan to return any donations to the Sacklers or the drug maker they own, Purdue Pharma, Tufts leaders said. Instead they plan to spend the donated funds for their intended purposes, like health science research.

Members of the Sackler family were not consulted as Tufts weighed what to do about buildings and funds carrying their name, but they were told before the university publicly announced its decision. A lawyer for the family blasted the move as an improper decision presented in an “intellectually dishonest” way, pledging to seek to have it reversed.

Tensions between universities and donors who have given money to name buildings, endowed funds and programs arise from time to time in higher education. But the Tufts situation has been closely watched because of its association with the opioid crisis ravaging the country and because it is playing out publicly. It also exposes two potentially competing interests hotly debated in philanthropic circles: an institution’s fundraising needs versus its stated mission and values.

Thursday’s decision comes after Tufts has been under pressure for months over its long-standing association with the Sackler family and Purdue Pharma, maker of the well-known drug OxyContin, which has been accused of fueling the opioid crisis with marketing tactics and influence campaigns.

Purdue Pharma filed for a controversial bankruptcy restructuring earlier this year as it faced thousands of federal and state lawsuits. The company has said it has been vilified even though it is just one of several opioid manufacturers, and it has described the opioid epidemic as a complex public health crisis.

Massachusetts attorney general Maura Healey filed allegations in court at the beginning of this year claiming that Purdue Pharma funded a program at Tufts to “influence Massachusetts doctors to use its drugs.”

The university responded by reviewing its ties to the drug maker and hiring a former U.S. attorney for Massachusetts, Donald K. Stern, to conduct an outside review of Tufts programs receiving funding from the Sackler family, their foundations and Purdue Pharma. Tufts released that outside review Thursday.

Stern’s team found that Purdue Pharma intended to use its relationship with Tufts to further its own interest and that in some cases “there is some evidence that it was successful in exercising influence, whether directly or indirectly.” It also concluded that “there was an appearance of too close a relationship between Purdue, the Sacklers, and Tufts.”

But investigators concluded funds received from the Sacklers and Purdue Pharma were not primarily used in areas related to opioids and pain management. In cases where funds in question were used in such areas, investigators found no evidence academic programs were “materially affected or skewed.”

“There was no influence, direct or indirect, on the academic program,” said Anthony P. Monaco, Tufts president, in an interview. “There was the appearance of and opportunity to, but no one acted in such a way that it actually materially influenced the curriculum.”

Tufts leaders did not base their decision to strip the Sackler name from campus on the Stern report, but they did wait to have the report in hand before making an announcement. As the report was being researched and drafted, university leaders solicited input from students, faculty members, alumni and leaders in the medical school, said Peter Dolan, chair of the Tufts Board of Trustees.

“We didn’t want to act prematurely before we had all the information in hand, but once we had that information in hand, that was background and context for us to then address the question of the Sackler name,” Dolan said.

A lawyer for members of the Sackler family, Daniel S. Connolly, issued a statement criticizing the university and promising to try to restore the Sackler name.

“Tufts acknowledges their extraordinary decision about removal of the family name from campus is not based on the findings of their report, but rather is based on unproven allegations about the Sackler family and Purdue,” the statement said. “There is something particularly disturbing and intellectually dishonest when juxtaposing the results of the Stern investigation with the decision to remove the name of a donor who made gifts in good faith starting almost forty years ago. We will be seeking to have this improper decision reversed and are currently reviewing all options available to us.”

The statement also described Stern’s report as finding no wrongdoing and no threat to academic integrity and concluding that Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family conducted themselves properly. It described the investigation as emblematic of negative stories surrounding the Sackler family, saying a careful look at facts finds negative stories to be “false and sensational.”

In another statement, a representative for Arthur Sackler's widow argued that he died before OxyContin was introduced and said she was saddened to see her late husband associated with actions taken by his relatives, The Guardian reported.

Healey, the Massachusetts attorney general, cheered Tufts.

“We applaud Tufts for this thoughtful and transparent review of its relationship with the Sackler family, for its recognition of the implications that relationship had on the mission and values of the university, and for listening to the voices of its students,” she said in a statement.

The president of the Faculty Senate at Tufts supported the university’s actions as well.

“The Tufts University Faculty Senate is proud of and strongly supports the decision made by the trustees, and we feel that it is an appropriate statement of the university's values,” said the Senate president, Melissa R. Mazan, who is a professor of large animal internal medicine. “The decision is in alignment with a resolution that the Senate passed unanimously last spring.”

Future Plans and Report Findings for Tufts

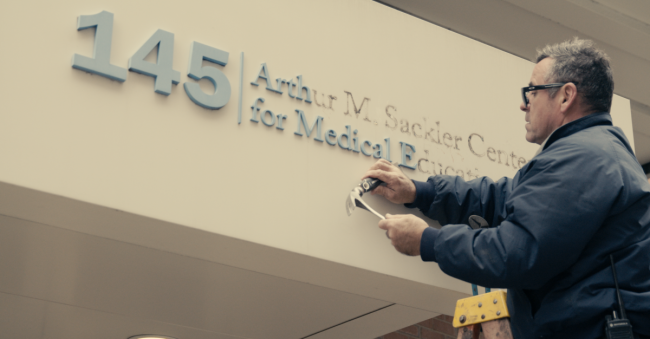

Tufts will strip the Sackler name from five different entities: the Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences; the Arthur M. Sackler Center for Medical Education; the Sackler Laboratory for the Convergence of Biomedical, Physical and Engineering Sciences; the Sackler Families Fund for Collaborative Cancer Biology Research; and the Richard S. Sackler, M.D., Endowed Research Fund. Changes to signs and websites are beginning immediately, but the university acknowledged that it will take some time to remove the name completely from all programs.

The university will establish a $3 million endowment dedicated to supporting education, research and civic engagement programs intended to prevent or treat substance abuse and addiction. And it will create an exhibit inside its medical school describing the Sacklers’ involvement with Tufts.

That exhibit will aim to teach lessons that should be learned from the opioid epidemic.

“We’re not trying to erase Tufts history by taking the names off the buildings and programs today,” Monaco said. “We want to make sure our community learns as we have.”

The outside review Tufts commissioned details a relationship between the university and the Sackler family dating to 1980, when three brothers, Arthur, Mortimer and Raymond Sackler, donated under a naming agreement for the Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences. The agreement, made years before OxyContin’s introduction to the market in 1996, came when the brothers owned a precursor company to Purdue Pharma.

The agreement didn’t specify how Tufts needed to spend the money, but some faculty members questioned the size of the donation and the “ethics of the Sacklers’ business practices which, though not specified in faculty meeting minutes, may have related to certain marketing practices employed by Purdue, even prior to OxyContin,” the report says.

Over the years, Sackler family members, their foundations and Purdue Pharma gave about $15 million to Tufts. Donations in the names of family members were for research but not related to opioids or pain research, the report says. Richard Sackler served on the school of medicine’s Board of Advisors for almost 20 years through 2017, but investigators found no evidence he discussed opioids or attempted to advance Purdue Pharma’s business interests as a board member. Tufts leaders traveled to Purdue Pharma's headquarters in May 2013 to give an honorary Ph.D. to Raymond Sackler. Tufts solicited donations from the family through early 2018.

Purdue Pharma made two sets of donations to the school of medicine -- to the Pain Research, Education and Policy program and to the Center for the Study of Drug Development. The report did not focus on the latter, finding no evidence of anything unusual or improper regarding its sponsored research. It found Purdue Pharma had the potential for direct influence over the Pain Research, Education and Policy program because of a 1999 funding contract that gave the company “far too much potential influence,” but it did not find evidence that the influence was ever exercised.

The report also described how a senior Purdue Pharma executive regularly lectured in two required program courses and eventually rose to adjunct associate clinical professor at the medical school, although he wasn’t compensated and disclosed his Purdue Pharma affiliation when lecturing. In 2017, three students felt he was sweeping the opioid crisis under the rug, but the report said it “does not appear that he exercised material influence with respect to the curriculum.”

Still, there appear to have been instances where the Sacklers and Purdue Pharma “exercised influence simply by virtue of the fact that they were donors,” the report said. It pointed to Raymond Sackler’s honorary degree and a committee in the school of medicine deciding in 2015-16 not to assign a book on the opioid crisis, Dreamland, that was critical of Purdue Pharma and mentioned the Sacklers. That selection was due in part “to the existence of the donor relationship with the Sacklers and Purdue and the desire to avoid controversy regarding that relationship,” the report said.

In addition the report cataloged situations that created the “appearance of an alignment between Purdue” and the Tufts Pain Research, Education and Policy program. They included the program’s co-founder appearing without pay in a 2002 Purdue Pharma print advertisement on fighting prescription abuse.

The report’s authors didn’t find any clear violation of university policies, but said the Pain Research, Education and Policy program funding agreement from 1999 “would not pass muster today under Tufts’ Gift Agreement policy” because of control allowed to Purdue Pharma. It also found no evidence of individual wrongdoing.

“Our overriding theme is that there is a greater need for specific guidelines, due diligence, careful review, and transparency,” the report’s authors wrote.

They recommended Tufts create stronger screening for donors, bolster conflict-of-interest policies, develop and make public guiding principles for gift acceptance, strengthen compliance practices and leadership, and take additional steps to keep “undue influence” out of academic and research programs.

Tufts leaders promised to follow those recommendations.

Questions for the Fundraising Field

The situation at Tufts invites a number of questions for the university’s philanthropic future as well as the field at large.

Tufts will have to examine the relationships it has with future donors as it follows the report’s recommendations. And when courting big gifts to name buildings or programs, it will have to contend with the fact that it pulled the name of long-standing donors from view in a very public process.

“We certainly looked at it from every possible angle as we made this decision,” said Dolan, the university’s board chair. “We considered the impact it might have on donors. Ultimately, we believe we’re doing the right thing and that our donor base will recognize this is the right thing for the university to do.”

But Tufts is not alone, fundraising experts said. Many universities and other nonprofit organizations are facing their past ties to controversial donors and reviewing the reputational risk of continuing to be associated with them.

“There is a growing scrutiny and worry about these things,” said Amir Pasic, dean of the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. “Sackler and [Jeffrey] Epstein have created a lot of salience for these kinds of reputational issues, and I think the constituencies are increasingly demanding and skeptical of prominent donors and their impact on communities. Students are much more worried and faculty are much more worried than in the past what it means for their institutions to have these powerful donors.”

Multiple constituencies on campus should be involved in developing policies to address the issues raised by controversial donors, said Deni Elliott, a University of South Florida media ethics professor and co-chair of the National Ethics Project. It’s a moment that can be used to teach students how to be active citizens and community members, and higher education leadership doesn’t capitalize on such moments enough, she said.

Not being open about the situation brings many types of risk.

"If students are taught ethics in the classroom and they don’t see ethics being practiced by leadership in higher education," Elliott said, "it makes the student cynical and not morally developed."