You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images

The University of California, Los Angeles, was the first university to openly propose using facial recognition software for security surveillance. Now it's the first to openly drop that plan. But whether other colleges are using the technology behind closed doors remains to be seen.

UCLA first floated the plan last year as part of a larger policy about campus security. Students voiced concerns during a 30-day comment period in June and several town halls into this year.

Fight for the Future, a national digital rights advocacy organization, launched its own public campaign against the UCLA administration's consideration early this year, in partnership with Students for Sensible Drug Policy.

“This victory at UCLA will send a pretty strong message to any other administration who is considering doing this,” said Evan Greer, deputy director of the organization. “It’s not going to be worth the backlash.”

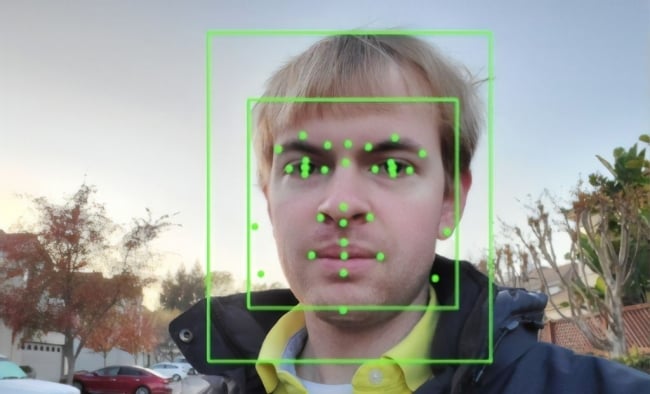

As part of the effort, Fight for the Future ran its own experiment. The group ran over 400 photos of UCLA athletes and faculty members through Amazon’s facial recognition software. They found 58 of those photos were incorrectly matched with photos in a mug-shot database. The majority of those false positives, the organization said, were of people of color. Some images the software claimed were the same person with “100 percent confidence.”

Fight for the Future had planned to release the results of the experiment to a news outlet, Greer said, but when that publication contacted the university, the response was swift. Within 24 hours a UCLA administrator wrote Greer to say the university was no longer considering using the software.

The attention from outside the university had been mirrored by backlash from within. Several student groups came out against the technology. Student leaders from the Community Programs Office -- the campus multicultural center -- organized three town halls on campus surveillance and submitted op-eds against the policy.

"As racially minoritized students at UCLA who have experienced over-surveillance and hyper-policing, it has been our responsibility to advocate and organize a space for students to learn about the policy and to engage the administration on voicing our collective concerns," said Oscar Macias and Salvador Martinez, student leaders from the multicultural center, via email. "For the past two years, students of color have worked tirelessly to achieve this historic victory."

Ultimately, the potential benefits of the technology were limited, a spokesperson for UCLA said via email, "and vastly outweighed by the community’s concerns.”

The university had not identified a specific software or made any concrete plans to deploy it, he said. The administration is now working to explicitly prohibit facial recognition software.

The Problem With Facial Recognition

The problems with the software are multifaceted, Greer said. It’s well documented that the current technology doesn’t always work as intended. It’s routinely bad at identifying women and nonwhite people.

That means those groups are more likely to face both the annoying aspects of being misidentified (like being locked out of a dorm) and the dangerous ones (like being wrongly accosted by police).

The technology is also susceptible to hacking.

“The scan of your face is a unique identifier, like your Social Security number,” Greer said. “But if your Social Security number gets breached, you can get a new Social Security number. If a scan of your face gets breached, you can’t get a new face.”

Students from the multicultural center said that in addition to putting people of color at risk, the technology could make vulnerable students less likely to access resources they need at the LGBT resource center or the Undocumented Students Program, for example.

Amelia Vance, director of youth and education privacy at the Future of Privacy Forum, said concerns around facial recognition should be particularly troublesome for higher education institutions. The systems are often particularly bad at correctly identifying children and young adults, she said. The software can cost millions of dollars and -- given that many episodes of violence are committed by students who attend those colleges -- is ineffective against violence.

“We just don’t have that much training data on children and on young adults,” Vance said. “This technology right now is not ready for prime time.”

Her organization has proposed a moratorium on facial recognition in public schools.

UCLA said it would consider using facial recognition in a “limited" capacity. One draft of the policy shared online by the student group Campus Safety Alliance said the technology would only be used “to locate a known individual for legitimate, safety or security purposes related to individuals who have been issued an official campus stay away order, court ordered restraining order, law enforcement bulletin or who pose a threat to one or more members of the campus community.”

That draft said a human being would need to examine the match before an official determination of someone’s identity could be made.

But Greer said that "limited" capacity -- security surveillance -- is one of the more concerning uses of the software.

“We’ve seen a few other schools that were trying to dabble with this technology,” she said.

Two other institutions in the state -- Stanford University and the University of Southern California -- had floated using facial recognition as part of their food service or dorm security. Students there would have been able to scan their faces to get into a dorm or pay for a meal.

While those uses normalize facial recognition and should be stopped, Greer said, they don’t ring the same alarm bells that surveillance uses do.

It’s possible that in the future the technology will improve, becoming more accurate and more secure.

For Vance, that’s one reason why her organization has called for a moratorium instead of an outright ban.

But to Greer, the possibility that the technology could become 100 percent accurate is even more frightening.

“That’s a world where institutions of power have the ability to track and monitor their people everywhere they go, all the time. That is a world where there are zero spaces that are free from government or societal intrusion, which is basically a world where we can’t have new ideas,” she said. “We really need to think about this not just as an issue of privacy but as an issue of basic freedom.”

If facial recognition software had been ubiquitous a few decades ago, she said, social movements like the LGBTQ rights movement may never have occurred.

“In the end it’s not really about safety -- it’s about social control.”

What’s Already Happening

UCLA chose to be open about considering facial recognition and solicited comments from students. For that, the university should be applauded, Vance said.

But that’s not necessarily happening everywhere.

“I would be absolutely unsurprised if multiple universities had adopted it and we just don’t know about it,” Vance said. Safety and security offices often act independent of other university administrators and may not be transparent about a new security measure.

Fight for the Future currently has a campus scorecard for facial recognition, keeping track of which colleges have pledged not to use the software. Though about 50 universities have told the organization they will not implement the technology, Greer said, many have said nothing at all.

“It is absolutely possible that there are other schools in the country that are already using this technology, they just haven’t told anyone about it,” she said.

The software is already in use by numerous municipal police departments and airports as well as at least one public school district. The Center on Privacy and Technology at Georgetown University Law Center found in 2016 that half of American adults are in a law enforcement facial recognition network.

Facial recognition software companies already are marketing to universities and K-12 schools.

“There are really no laws in place that would require private institutions, for example, to even disclose to their students that they’re doing this,” Greer said. “We really do need policies in place so that it’s not up to school administrators.”

Vance pointed out that university leaders and policy makers often bemoan that a younger generation doesn’t care about privacy.

“They clearly do care about privacy,” she said. “And this is a step too far.”

(Note: This article has been changed from a previous version to include comments from student leaders.)