You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

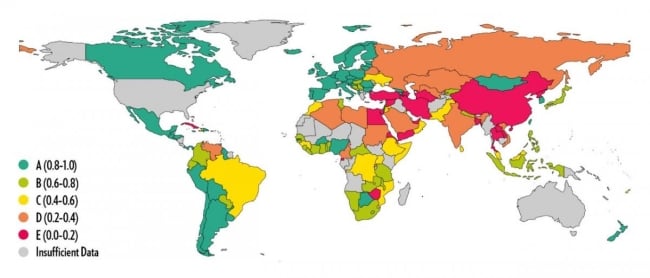

Global Levels of Academic Freedom 2019: Status Groups According to Academic Freedom Index (scale 0-1). Countries with "A" rankings have the highest score, and those with E rankings have the lowest. Countries in gray are not rated due to insufficient data.

Global Public Policy Institute

Comparative data on academic freedom has been hard to come by, but a new index released Thursday assigns ratings to countries based on how free scholars are to teach and research.

The index relies on expert assessments of five measures related to freedom to research and teach, freedom of academic exchange and dissemination, institutional autonomy, campus integrity (defined as the degree to which campuses are free from politically motivated surveillance or security-related infringements), and freedom of academic, cultural and political expression.

“We had two different objectives. One was an academic objective and another one more policy/advocacy related,” said Katrin Kinzelbach, a professor of political science at FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, in Germany, and one of the developers of the Academic Freedom Index. The index, which goes by the abbreviation AFi, is a collaborative effort by FAU; the Global Public Policy Institute, a Berlin-based think tank; the Scholars at Risk Network, a New York-based organization that monitors academic freedom conditions and assists threatened scholars; and the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute, which is based at the University of Gothenberg, in Sweden.

From an academic point of view, Kinzelbach said the research team wanted to move beyond incident-tracking data -- which typically focuses on discrete events that constitute academic freedom violations -- to understand conditions for academic freedom more broadly, “not just violations but to understand improvements.”

The second objective is more advocacy-related. A paper describing the index and findings outlines how the data can be used by universities, governments, individual students and researchers, and others -- including major university rankers, which do not currently factor academic freedom into their rankings. Universities in China in particular have climbed up rankings tables quickly even as many scholars have raised concerns about deteriorating academic freedom conditions.

“Academic freedom must be resurrected as a key criterion for academic reputation and quality,” the paper states. “AFi country scores can be used to improve established university rankings. At present, leading rankings narrowly define academic excellence and reputation as a function of outputs. As a result, institutions in repressive environments have climbed the reputation ladder and now occupy top ranks. They thereby mislead key stakeholders and make it possible for repressive state and higher education authorities to restrict academic freedom without incurring a reputational loss.”

The developers of the index argue that universities' rankings could be adjusted upward or downward based on the academic freedom conditions in the countries in which they're located.

“The argument which has been made previously -- that we do not have comparative data on academic freedom and therefore cannot factor it into such rankings -- no longer holds, because we have presented data,” Kinzelbach said.

Ben Sowter, the senior vice president for QS, a major global university ranker, said QS is interested in exploring these kinds of metrics.

“We have always tried to avoid building environmental constants into institutional rankings -- for example, tuition fees or salary after graduation are problematic, because they reflect relative exchange rates from one year to the next as much as the actual achievements and capabilities of the institution,” Sowter said. “However, we are exploring ways to provide additional data alongside the rankings as tools by which a user can filter, customize and contextualize our results, and we would be interested in exploring metrics like this through that kind of mechanism as long as they are robustly compiled themselves.”

Phil Baty, the editor for Times Higher Education World Universities Ranking, another major ranker, said "THE’s approach to rankings is to proactively acknowledge that there are many different types of excellence in global higher education, from teaching and research, of course, but also including social mobility, knowledge transfer, societal impact and many other aspects. So THE has developed a wide range of metrics for a wide range of institutional missions and priorities, recognizing that there is no one-size-fits-all model."

He mentioned a new ranking THE is doing to measure universities' impact on societies through the framework of the United Nations' sustainable development goals.

"When we look at universities in in relation to the SDGs, we look at their research and teaching, of course, but we also look at their stewardship of their own affairs: how they treat their staff and students, for example, how they manage their own consumption, and … whether they have strong governance systems, including clear policies on academic freedom," Baty said.

A total of 1,810 scholars contributed data for the Academic Freedom Index. The index does not report data for 35 countries -- including the United States and Australia -- for which it did not have enough expert coders. Kinzelbach said she hopes that will be fixed for the next round of data.

“Apparently it is often difficult in high-income countries to excite academics to contribute to a larger research project of this kind where they don’t have a publication related to it," she said.

Countries are divided into one of five brackets based on their overall academic freedom score (see image above). Countries falling in the worst category include China and the United Arab Emirates, two countries with which many American universities have substantial partnerships. Other countries falling into the bottom bracket as far as academic freedom is concerned are Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Cuba, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Iran, Laos, North Korea, Syria, Thailand, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Yemen and Zimbabwe.

Coders provided ratings of countries going back to 1900 or when the first university was established in a given country, whichever was more recent. The report highlights five countries where AFi scores have increased by 10 percent over the last five years, suggesting improvements: Armenia, Ethiopia, Gambia, Sri Lanka and Uzbekistan.

The report also identifies countries for which there was a 10 percent drop in AFi score over the last five years, suggesting a worsening of conditions: Benin, Brazil, Hong Kong, India, Libya, Mozambique, Pakistan, Turkey, Ukraine and Yemen.

Brazil and India had the steepest declines over the last five years. The developers of the index say they welcome healthy debate on these findings.

"While there is evidence of a deteriorating condition for academics in both countries, the extent of the AFi score’s decline seems somewhat disproportional in comparison to earlier periods in the countries’ history, as well as in comparison to other countries over the same period," they write in the report.

"In this context, it is important to reiterate that AFi coders are typically academics who work in the country that they assess. Their concerns and fears are reflected in the data. We believe that this intrinsic feature of expert-coded data must be openly discussed. Recent deteriorating trends should be read as important warning signs that depict the current climate among academics in the country. However, we also encourage substantiated, scholarly debate on the data, as well as additional expert assessments in future rounds of data collection that allow for a retrospect evaluation of the situation."