You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

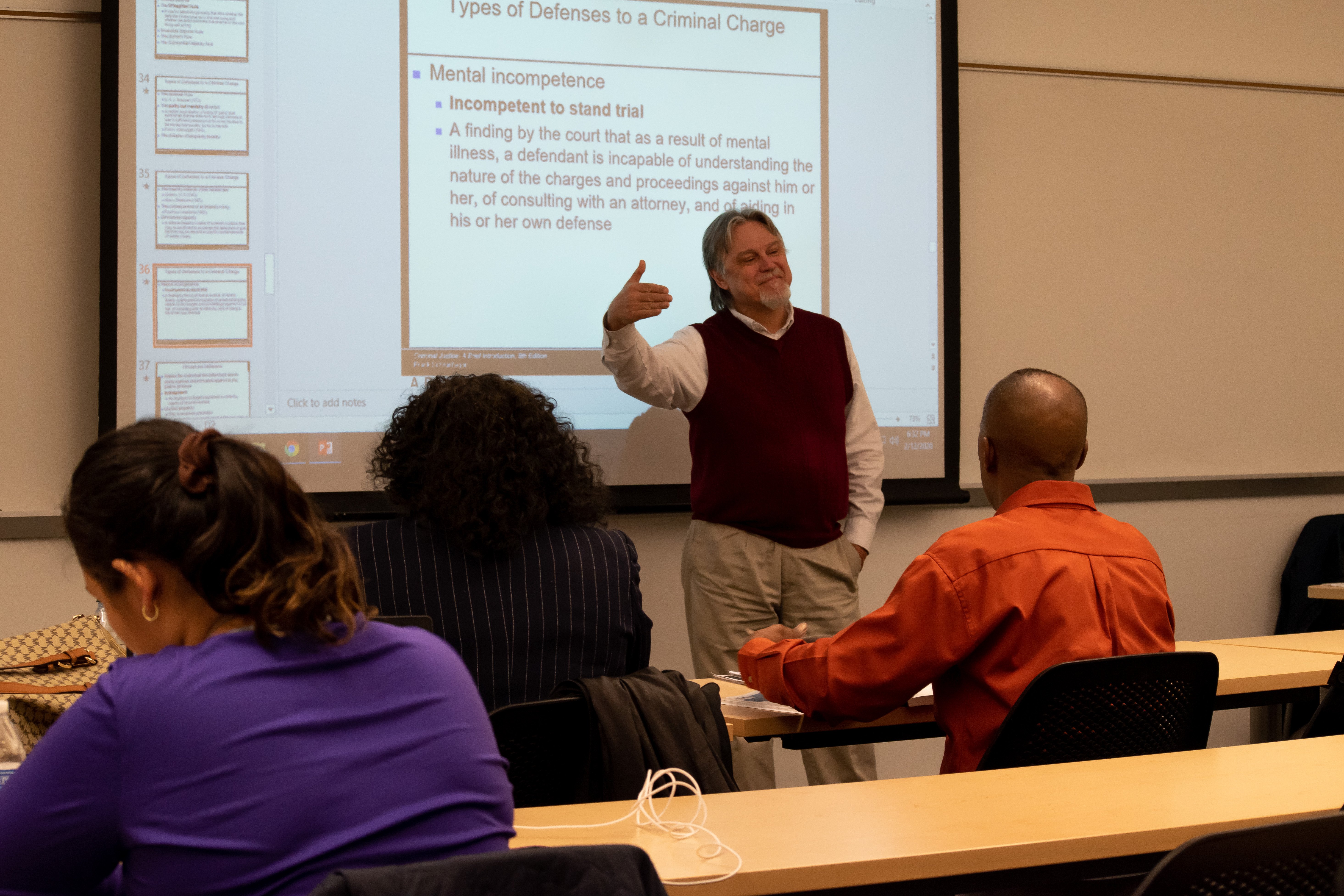

Thomas Mostowy, associate dean for the School of Professional Studies at Trinity Washington University, teaches a night class to adult students in February.

Madeline St. Amour, Inside Higher Ed

Faculty are crucial for students. They serve as instructors and mentors. They connect students with a network that will help them succeed and get good jobs in the future.

But they can also get in the way.

As the student population shifts away from the traditional 18-year-old heading off to live in a dorm to students who are older and lower income, institutions and their faculty members are struggling to find mutually agreeable ways to support nontraditional students.

That means colleges and universities struggle with how to motivate faculty to serve different students. And some faculty members struggle with how to adapt.

“When I hear a faculty member complaining about students all the time, I know that’s a signal for discussing retirement on the horizon,” said Patricia McGuire, president of Trinity Washington University in Washington, D.C.

While the big-name colleges still enroll plenty of stereotypical students, the institutions that serve the bulk of students have seen changes.

The numbers are clear: 37 percent of today’s students are older than 25, according to information collected by Higher Learning Advocates. Almost two-thirds, 64 percent, work while in college. Another quarter or so are parenting. About half, 49 percent, are financially independent.

Almost one in three, 31 percent, live at or below the federal poverty level.

And those were the numbers before the novel coronavirus shattered the country's economy. The full effects of the virus aren't yet clear, but it seems likely to add financial pressures on students in the coming months and years.

The issue of aligning faculty skills with students' needs goes beyond the stereotypical trope of an old, cranky professor who doesn’t like change, though. Challenges to overcome can be as simple as the hidden language of academia and faculty assuming all students have the same understanding of common terms on campus.

How does a student know the meaning of office hours if the student has never before heard the term?

The issue might be carelessness or thoughtlessness -- like assuming students don’t have responsibilities outside of their coursework. It might also be unintentionally carrying on one mode of teaching for years without analyzing why students are dropping out of courses.

The answer to this is not simple. Getting faculty to adapt to the times takes planning, buy-in and, most importantly, money.

But it’s necessary. For faculty who seem unwilling or unable to adapt, McGuire tends to have conversations about whether they still feel excitement about teaching. If professors don’t want to explore new pedagogies or approaches to teaching, that’s a sign they’re worn out, she said.

Some policy experts, institutional leaders and advocates believe higher education must change the way it trains, hires and promotes its faculty. Others say the blame is misplaced and instead point to structural issues like declining numbers of tenured positions, the importance of leadership and the need for more investment in teaching and learning.

Whatever the case, institutional change is now a necessity, as the demographics for students and the general population shift. The number of white students is decreasing as the number of Hispanic students increases, among other changes.

Higher education is facing an enrollment cliff by 2026, when the full impact of a declining birth rate will hit colleges. The last decade was a precursor to these changes. Enrollment across postsecondary institutions has been falling since 2010.

To combat this, institutions are turning to certain segments of the population that seem like potential enrollment gold mines. About 36 million American adults have some college credit but no degree, prompting marketing companies to sell services to colleges designed to target this demographic. Make no mistake -- most teens still plan to enroll in college. But many will bring with them different life experiences from the traditional college students of yore, who tended to rely on family for support instead of working full-time themselves.

However, the majority of faculty are privileged. Most are white men. Those who are on the track for tenure are older than the average American worker, placing them further away from the modern-day experiences of their students. While there have been some gains in diversity, most of them stem from contingent faculty.

This challenge is now more important to understand than ever, as the novel coronavirus upends higher education, leaves many students unemployed and takes away services like childcare.

‘Hidden Culture’

Some faculty don’t recognize how the demographics, and thus the needs, of students are changing, according to Davis Jenkins, a senior research scholar at the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University.

When Jenkins works with faculty and advisers to map out a student’s journey through a college, “it’s just shocking how many barriers the student faces,” he said.

At issue is a gap between many professors’ own experience and that of their students.

“You have professors, potentially, who make the assumption that your schooling is the same as my schooling,” said Sean Morris, director of the Digital Pedagogy Lab at the University of Colorado at Denver. “Even within a generation, that’s changed.”

It’s something all types of institutions will have to address, Jenkins said, as enrollments decline and too many students leave college without degrees.

Some colleges have already recognized the need to change. Since the 1980s, Trinity Washington has been catering to what McGuire calls post-traditional students.

“Over time, we’ve learned a couple of things,” she said.

Those include hiring faculty “who are capable of teaching the students we have, not the students they wish they had.” They are willing to teach outside of typical daytime hours and can work with students who may need leeway at times.

The last piece is “compassionate rigor,” McGuire said.

When students set foot on campus, they encounter a hidden culture.

“For adult students, you have the added dimension of stresses from work and family life,” she said. “At the same time, students need to be disciplined, so what’s the balance between helping and being taken advantage of?”

An example could be giving students one free pass for redoing an assignment or retaking a test.

Beyond understanding the external obligations students have, faculty need to understand what may pose challenges inside the academy. Colleges as a whole often take for granted that students will arrive on campus already knowing how things work, said Anthony Abraham Jack, assistant professor of education at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education.

Sometimes, it’s an unintentional systemic issue. For example, a college dean once told Jack about a student who thought office hours were a time for professors to work and not be bothered.

“When students set foot on campus, they encounter a hidden culture,” Jack said. He will often train faculty and staff to recognize this when giving talks on campuses.

Other times, the words are more personal. Students who are also parents will hear their professor tell the class that they can take on extra work because they don’t have “real” responsibilities. Or professors will get angry with students for not buying all of the -- often expensive -- books for a course.

“The gap in understanding is still prevalent,” Jack said. “You have to have a cultural shift in conjunction with a structural shift, especially in the context of the changing student body.”

Some blame the reluctance to change on what they call deficit thinking. If faculty expect students who don’t fit traditional molds to fail, then they are much more likely to fail.

“A lot of times, faculty don’t think about where students are coming from,” said Audrey Dow, senior vice president of the Campaign for College Opportunity. If faculty see a student falling asleep in class but don’t know that student just worked a 10-hour shift, they might assume the student isn’t college-ready. But that student might just need support, Dow said.

“When we look at students and say, ‘Gosh, they’re showing up, they want an education, how do we help them get it?’ that’s when success can happen,” she said.

Supporting Faculty to Support Students

Supporting Faculty to Support Students

Some say higher education must look at structural issues before it places the blame on faculty. They balk at the idea that faculty are the primary problem.

“I think that that is a very dangerous framing of what is a very real challenge that needs to be addressed,” said Alison Kadlec, a founding partner at higher education consulting firm Sova Solutions. “From what we know from our work, as well as from research in related areas, the people who are closest to students are [faculty]. In any institution, they are also the single greatest reservoir of commitment.”

One of their biggest obstacles is the conditions faculty work under, she said, because those conditions can easily preclude them from being truly effective. Systematic adjunctification, for example, makes faculty feel devalued and makes it difficult for them to go the extra mile because of low pay and instability.

For faculty who work contingently, it can be hard to do creative work, said Jesse Stommel, a senior lecturer of digital studies at the University of Mary Washington and executive director of Hybrid Pedagogy, a journal for digital pedagogy. The stresses from that precarious job position, which often provides little security and doesn’t pay well, make experimentation with pedagogy and teaching difficult.

“When we defund public education, when we make the work of teaching increasingly precarious, we make it extraordinarily difficult to do this work,” he said.

Institutions should help faculty understand who their students are, said Sherri Hughes, assistant vice president of professional learning at the American Council on Education. But faculty still hold responsibility for teaching them.

Saying “we shouldn’t put it all on the faculty member,” she said, “suggests that nontraditional students are a burden, and I don’t think that’s true.”

Understanding the different practices, tools and approaches to teaching is important for teaching all students, not just nontraditional students, she added.

At Trinity Washington, the university has won grants to support those kinds of efforts. A Howard Hughes Medical Institute grant to support women of color in science, for example, provided resources for science faculty to revise their curriculum and get training.

The reaction so far has been positive, according to Cynthia DeBoy, associate professor of biology at Trinity Washington and a director of the grant programs. A training about motivating students held on a Saturday attracted all science faculty members, and they stayed until after 5 p.m. It led to the creation of mentor moment courses at the university, which focus on different life skills, like self-advocacy and applying to internships, for each year of a student’s time in college.

Ultimately, colleges need to hire more full-time faculty, according to Adrianna Kezar, director of the Pullias Center for Higher Education at the University of Southern California. Those who are full-time can do what many contingent faculty don’t have the supports to do: hold more office hours, stay after classes to have conversations with students and support outside activities like clubs.

“Research shows, for first-generation, low-income and underserved minority students, that faculty members who are supportive are by far more important than things like advising,” Kezar said. “Just at a time where the student body really needs the faculty, we’ve really taken away the ability for faculty to support them.”

‘We’re the Ones on the Ground’

Large-scale changes that could improve student success at scale often face opposition from faculty members, policy experts say.

One of the most obvious examples is the battle over developmental education reforms. In several states, faculty unions have fought against legislation to adopt models like corequisite courses.

“What happens in the classrooms could be most critical for students,” said Wil Del Pilar, vice president of higher education policy and practice at the Education Trust. “Faculty need to be willing to change their pedagogy based on students, or be more flexible.”

In California, legislation that allowed more community college students to skip remedial courses and instead take courses that would transfer with credit to four-year institutions was met with opposition by some faculty.

Faculty lamented what they call legislative intrusion. The reason why is simple, said Susan Holl, professor emeritus at California State University, Sacramento, and chair of a subcommittee of the Faculty Senate.

“We’re the ones on the ground,” she said. “All educational strategies don’t work for all students.”

It’s frustrating to see legislators think they know best, Holl said, especially when they push for change very quickly. The faculty she works with are very committed to student success, she added.

“The pushback comes from people telling faculty how best to do their business, when we know how to create programs and curricula,” she said.

Holl suggested that advocates go to faculty governance bodies first with proposals for significant changes, such as developmental education.

“Although we appreciate that people are well meaning,” she said, “we would like any legislators, any people who hold the purse strings, before they make any rules or legislation or listen to advocacy folks, to make sure they work with the faculty at whatever level to understand what the real issues are on the ground.”

The pushback can also be unintentional. It’s unfair to vilify faculty who teach using lectures, because it’s often an issue of awareness, said Josh Eyler, director of faculty development at the University of Missouri.

“We have a ton of research on how people learn and the teaching strategies that are most effective in maximizing that learning,” Eyler said. “To the degree that we can send that message and spread that word and shift the culture of the university toward teaching strategies rooted in that evidence, the better we’ll be.”

To that end, institutions should incentivize and support faculty in learning more about their craft, Eyler said.

Stommel thinks faculty should engage students more in their courses. The surest way to do so is to not design courses ahead of time, but rather ask students to help construct them.

“When we lock that stuff in stone before we’ve interacted with the students, then we’re not actually building a learning experience for the students we actually have,” he said. “We’re building a learning experience for an imaginary student.”

While some might assume this model takes the rigor out of college, Stommel said it can do the opposite. If students take ownership of their learning, they will put in more effort and be more engaged, he said, whereas it can be easier for them to “go on autopilot” while following someone else’s goals and trajectories.

A Small but Vocal Group

Many higher education experts said they believe the issue of faculty being a barrier to student success arises from a “small but vocal group” of professors. “And they have tenure,” said Morris, the professor from CU Denver.

Morris studies pedagogy and learning, and he contends that the typical way college faculty teach -- lecture style -- won’t work with the “new traditional” student.

“There’s a divide between teachers and students in the classroom, and that needs to start to break down,” he said. “Traditionally, the teacher is a taskmaster.”

If learning were more cooperative and collaborative, then nontraditional students could bring their life experiences into the class, Morris said. When this can’t happen, faculty have to take special measures to know what’s going on in their lives and what challenges they may have.

Most faculty also never learn how to teach, according to Del Pilar. Institutions, he said, tend to value faculty’s ability to be content experts rather than teachers.

“They are not trained to meet the different learning outcomes or style of everyone, or the unique needs of students,” he said. “They’re trained on, ‘How do I get the information across? Here’s how I learned it, here’s how you’ll learn it.’”

Achieving the Dream, a nonprofit network of community colleges focused on student success, is working to address this issue by encouraging its members to invest in centers focused on teaching and learning, said Karen Stout, the organization’s CEO and president. These centers can teach faculty how to empathize with the myriad of experiences today’s students bring to the table, as well as raise awareness about nonacademic supports on campus so faculty can correctly refer students.

There’s a divide between teachers and students in the classroom, and that needs to start to break down.

Both Morris and Stout said most faculty want to learn about effective teaching methods.

“If you engage them in conversations about relational teaching, they eat it up,” Morris said. “Because they go into a room and their students are staring at them, and they have to try to make learning occur.”

At Miami Dade College, a community college in Florida that won the 2019 Aspen Prize for College Excellence, faculty have access to the Center for Institutional and Organizational Learning.

Julie Alexander, vice provost of academic affairs at the college, cited hundreds of opportunities for training each year. Academic affairs also has personnel dedicated to the long-term strategy for faculty development. Adjunct faculty are paid to attend mandatory training, and some voluntary opportunities are also paid, Alexander said.

“One thing that I hear a lot from students is that they feel like this is a very receptive environment, and that the faculty are aware of not only their capacities, but also that there are challenges outside of academia,” she said.

Some also question the focus of tenure and the reward structure on which it’s built. For example, at institutions with a heavy research focus, faculty members can lack incentives to strive to perfect their teaching strategies.

It’s difficult to quantify effective teaching, said Sally Johnstone, president of the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems, while it’s “easy to count publications.”

Still, if institutions want more effective teaching, they have to promote it from the top down. When Morris was a graduate student teaching a class at the University of Colorado at Boulder, he said he was told by his department chair to not worry about the teaching, but instead focus on his own studies.

“I was teaching 50 undergrads who needed a teacher, but I was told not to care,” he said.

While it’s easy to assume research universities would emphasize research over teaching, and vice versa with community colleges, Johnstone said the focus varies across colleges.

“It has to do with the leadership of the institution and how committed they and the board are to really having the focus on student success,” she said. “If that’s there, then there are other things they can do for all students to be successful.”

Changes Done Right

Many colleges are starting to make changes to address these issues as the current environment forces them to innovate or risk failure.

There are different approaches to how to involve faculty in that change.

“When you talk to people who are trying to create institutional change, engaging faculty in that change makes it more sustainable, but it also makes it a longer game,” Del Pilar said. “Do you implement what you can today to help students now, or play the long game to help students in six years? I think the answer is both-and.”

At Georgia State University, administrators took this approach and first addressed issues that didn’t require faculty involvement.

“When we launched these efforts over a decade ago now, the focus was on the university trying to correct the problems that the university itself was creating,” said Tim Renick, senior vice president for student success at Georgia State. “We wanted to ask how we were the problem.”

Some of the first big projects included improving academic advising, changing the distribution of financial aid and launching a chat bot to help students more immediately with problems, he said.

While those initiatives were done without faculty, Renick said, it didn’t create resentment. Rather, he said, it showed “that this was not an attempt to attack them. It was an effort to show that we all have to address issues.”

Do you implement what you can today to help students now, or play the long game to help students in six years? I think the answer is both-and.

Because the changes started by looking at the problems at the university level, rather than shoving blame onto faculty, Renick said it encouraged faculty to spearhead their own projects.

There still was pushback, he said. But it tended to come from a small group.

“I think most faculty come into higher education, and certainly most faculty come to a place like Georgia State, because they care about making a difference,” Renick said. “In many cases, the university deadens that idealism because it’s such a big bureaucracy, and younger faculty want to change things, but they can’t.”

Once faculty saw how the changes -- like moving to low- or no-cost materials or using predictive analytics -- helped improve the graduation rate, they once again had hope that they could make things better, he said.

The approach has worked, according to Michelle Brattain, chair of the Senate Executive Committee and chair of the history department at Georgia State

“The university has not demanded anything. They’ve persuaded [faculty],” Brattain said. “I think if the university put all the responsibility for student success on faculty, it wouldn’t have gotten buy-in.”

Use of data analytics also convinced faculty members to take the administration’s work seriously, she said. The administration’s willingness to help with problems students face also sets the tone for the university overall.

For example, Brattain said, one student broke his glasses and couldn’t afford new ones, and he couldn’t do work because of it. She emailed a vice president at the college for help, and that staff member found a grant for the student to get new glasses.

“No problem is too small for them to be concerned about it,” she said. “It makes a huge difference.”

Many believe that including faculty in student success initiatives is key. Stout, of Achieving the Dream, said she sees faculty leading the change in many places.

“I don’t believe that faculty are the barrier for nontraditional student success,” Stout said. “I believe the systems and structures in our colleges are the barriers.”

One example is Pierce College in Washington, where faculty are now using data to improve student success at the course level.

The change started when the institution decided to focus heavily on student success, said Greg Brazell, director of employee engagement, learning and development at the college. It instigated a change in how the college provides professional development to its faculty.

“Before, it was the traditional, one-and-done, just-in-time model,” Brazell said. To make development more sustainable, the college created action research project opportunities for faculty. This year’s theme for projects is equity.

Faculty are becoming evidence-based practitioners on teaching practices, he said. They can look at data at the course level to determine which students are not succeeding and why that might be. Maybe students can’t get homework done during the week, or maybe the faculty member is teaching a particular lesson too quickly.

As a result, the college has raised its three-year graduation rate from 18.7 percent to 36.2 percent since 2010.

“The current culture is very open,” he said. “It’s all about student success.”

I believe the systems and structures in our colleges are the barriers.

McGuire, president of Trinity Washington, said it’s important for university leadership to find “champions for change” among the senior faculty, as well as provide incentives through paid training or grant opportunities.

“You do have to fund faculty time and recognize that there’s a value worth paying for,” she said.

The university has a committee that acts as a “faculty salon” where professors will present their work on student success, which can naturally bring about change.

One discussion centered on whether faculty should accommodate a student who had a childcare problem and needed to bring their child to class for a day, McGuire said. Half said yes and half said no, and then they discussed it.

“Everyone went away realizing they should be humane and let someone do that if they need it for an emergency,” she said.

While institutions have been focusing on student success over the past decade, Kezar, of the Pullias Center, said the next area of focus is student services.

“The big move for the next 10 years really needs to be, ‘OK, we’ve done some really good thinking about students and some of the things that shape and affect them, but we haven’t really considered the classroom,’” she said. “That has always been left out of the student success movement. That’s what we need to focus on now.”