You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

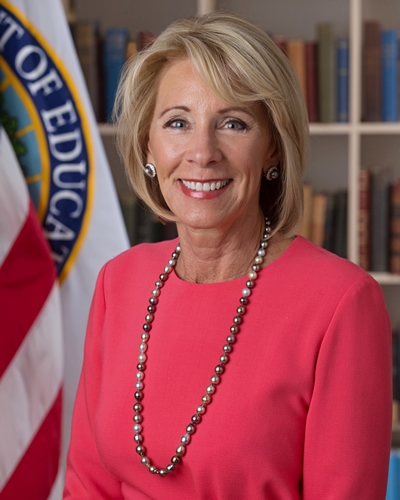

Education Secretary Betsy DeVos

U.S. Department of Education

About $4.7 billion, or three-fourths of the $6.3 billion in emergency student grant funds Congress authorized in the CARES Act, has been sent to more than 2,000 colleges and universities, according to the Education Department.

In addition, 3,482 institutions, or about two-thirds of the 5,136 eligible to get the grants to pass on to their students, have now applied, up from a half a week ago, the department told Inside Higher Ed.

But while that was seen as a positive even by critics, colleges and the group representing campus financial aid administrators say the department is interpreting the language in the congressional stimulus package so narrowly that many students are being excluded from getting help.

While the controversy over U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos’s decision to exclude college students brought illegally to the U.S. as minors has been well publicized, critics say guidelines released by the department also exclude other students for having bad grades or having defaulted on student loan payments.

In addition, Justin Draeger, president and CEO of the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators, said guidelines the department issued a little more than a week ago have confused campuses and slowed getting the grants into the hands of needy students who are struggling to pay for housing and food.

The guidelines included in a Frequently Asked Questions document from the department excluded so-called DACA students, who were given the right to work and live legally in the U.S. under the Obama administration’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program.

Just as congressional Democrats and a variety of immigration and civil rights groups say DeVos went beyond what Congress intended, critics also are accusing DeVos of overreach in saying in the guidance that only those who qualify for federal student aid can get emergency grants. The guidance also said that those who haven’t filled out a Free Application for Federal Student Aid would qualify if they are deemed eligible for student aid.

Imposing the same requirements for getting the grants as for getting financial aid limits who can get help at a time when many students are in dire need, Draeger said. Federal student aid requirements contain a long list of conditions, from not having defaulted on student loan payments to making satisfactory academic progress, defined as having a C average.

“A student who had a minor drug conviction, who was attending school and had to move off campus and incurred significant moving costs, wouldn’t qualify,” Draeger said in an email. “Neither would a student who needed to purchase a laptop to stay enrolled as their school went online, but didn’t register for selective service.”

He added, “Or what about a student who defaulted on a loan, hasn’t rehabilitated it yet, but came down with COVID-19, incurred significant medical expenses? Or how about a student who was recently married and fails a Social Security match because they haven’t updated their SSN information? Obviously they are an eligible citizen, but they’ll have an SSN error, which at the very least will delay their grant.”

As with the DACA issue, the question of whether Congress intended only for those who qualify for student aid to get the grants is causing a partisan divide.

Republican aides have told Inside Higher Ed the CARES Act did mean to exclude DACA students, while Democrats, including several who wrote DeVos this week, insist undocumented immigrant students are supposed to get emergency grants.

Similarly, whether Congress intended to limit which other students could get the grants depends on whom you ask. And the answers are somewhat contradictory.

Late Tuesday night, the Education Department said it was doing what Congress wanted by limiting emergency grants to those who are eligible for Title IV student aid.

“The department is implementing the CARES Act as it was written by Congress,” the statement said. “Of course, institutions are free to give funds from their endowment or other funds to students who do not qualify for Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund grants. But unless Congress changes the law, institutions cannot use the federal taxes paid by lawful American citizens and residents to do so.”

But earlier on Tuesday, Republican aides on both the Senate’s education and appropriations committees said Congress meant to leave it up to DeVos to decide who should get the emergency help.

“Congress allowed the secretary to determine criteria to target aid to the most needy students, and providing aid to Title IV-eligible students seems like a reasonable criteria,” the education committee aide said.

Their Democratic counterparts on the two committees, as well as on the House education committee, didn’t comment. on what they intended.

But the CARES Act says only that institutions have to use at least half of their stimulus funds on the emergency grants and places no limits on which students should be eligible, said Draeger and David Baime, the American Association of Community Colleges’ senior vice president for government relations and policy analysis. They saw that as an indication that Congress meant for the grants to be spread widely.

Conflicting Messages

Meanwhile, of the colleges allocated the 10 largest amounts of stimulus funds for emergency aid, six -- Arizona State University, Pennsylvania State University, Rutgers University, the University of Central Florida, the University of California and Miami Dade College -- said they are still trying to figure out how to determine whether a student is eligible and how to distribute the grants.

A seventh, Ohio State University, is asking students to fill out a request for emergency funds that asks for a description of the hardship they’re facing. A university spokesman didn’t respond when asked how the university will determine if the student is eligible for the grant.

None would comment on why they haven’t yet established a procedure. But Draeger said the guidance also created a number of questions for colleges, like how to determine if a student is eligible for financial aid and the grants if they haven’t filled out a FAFSA.

Part of the problem for colleges is that the department has sent campuses conflicting messages, said Baime of AACC.

A week before issuing the Q&A, DeVos said in calls with reporters and stakeholders that she would be giving colleges wide discretion in deciding who should get the grants. In response, Draeger said, some campuses started developing their plans for distributing the money to all who needed it, only to be told by the department that many are not eligible, and making colleges go back to the drawing board.

“The Department of Education deserves credit for expeditiously making funds available to colleges,” Baime said. “At the same time, conflicting and often vague guidance has made it difficult for some institutions to develop policies for using funds.”

Luis Maldonado, the American Association of State Colleges and Universities’ vice president for government relations and policy analysis, also noted that while three-fourths of the money has been given out, only about half the eligible institutions have gotten funds. He worried most of the ones that haven’t gotten the grants are smaller institutions less able to handle applying for the money.

Waiting for Guidance

Officials at several colleges, meanwhile, gave a mixed picture of trying to get the emergency grant in students’ hands.

One financial aid administrator, who is a member of Draeger’s group and didn't want to be identified, said their college at first assumed from DeVos’s initial statements that it could give all students help. It planned to divide up the grant money widely in small amounts.

The college now doesn’t want to start handing out the grants in small amounts, because unless the program is expanded to more people, it will have money left over.

But if it were to start giving out larger grants, and the department later allows more students to be eligible, then the institution will have spent too much.

“We're not awarding anything right now,” the administrator said. “We're going to give this a little time to see what shakes out.”

Luoluo Hong, associate vice chancellor for student affairs and enrollment management for the California State University system, said figuring all this out only adds to the challenges of creating a new program when financial aid staff are working remotely and students are off campus.

Some California State campuses are giving grants to those they know qualify because they already are receiving federal aid and then waiting for more department guidance on how to use what’s left over. Some of the campuses are asking students who want help to fill out a FAFSA, while others are just asking students to certify that they are eligible, which Draeger says raises the question of who is liable for paying back the money if a student ends up being ineligible.

Meanwhile, Cal State is looking to see if it can come up with its own funds to give grants to DACA and international students. “These dollars were intended to mitigate the financial impacts of COVID-19 on students, so it should be for all students,” Hong said.

The issue is less a problem at Georgia State University, said Timothy Renick, senior vice president for student success at the downtown Atlanta institution.

The university has given out $560,000 in emergency grants during the pandemic from a fund it already had in place from private donations. Georgia State is reaching out to 100,000 potential donors to add to the $300,000 it has left, he said.

It will give the CARES funds to those they know qualify and tap into the private donations to help the rest, including DACA students.