You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The closure of academic testing centers due to the coronavirus pandemic has been a boon for the Duolingo English Test, a computer-adaptive language proficiency test that can be taken at home in 25 to 35 minutes and that is increasingly used by colleges to determine whether to admit international students.

Even before the pandemic, the DET was gaining ground in college admissions. Champions of the test praise above all its accessibility: it can be taken online anytime, anywhere, in less than an hour, for the cost of $49. By contrast, the two largest and most established tests in this space, the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) and the International English Language Testing System (IELTS), take about three hours to complete (IELTS takes two hours and 45 minutes), are traditionally administered in testing centers and cost in excess of $200.

Critics of the DET say you get what you pay for. They argue that Duolingo’s test, with its focus on word- and sentence-level tasks and paragraph-length writing and speaking prompts, should not be relied upon as a measure of students’ ability to engage with academic texts and use English in a university setting. The critics have also raised questions about the security of an at-home test. (Duolingo outlines the security measures it takes on its website.)

In any case, DET is no longer the only take-home test around. The makers of TOEFL and IELTS both rolled out at-home versions of their own tests after testing centers were forced to close -- but not before DET made significant inroads.

“We are seeing pretty staggering growth due to the pandemic in the number of colleges that have started accepting the test,” said Jen Dewar, the head of strategic engagement for the DET. She said about 1,000 new academic programs started accepting the test since the end of January, when standardized testing centers closed in China, bringing the number of programs accepting the DET to about 2,000.

Duolingo also reports dramatic growth in the number of individual tests taken. Dewar said the company saw 700 percent growth globally in tests since Jan. 1 compared to the same period last year, and 1,000 percent growth in the number of tests given in China.

Dewar said acceptance of DET by colleges was already growing before the pandemic, “but the pandemic has certainly accelerated the interest institutions have in the United States.”

A scan of university admission websites shows a mix of policies among colleges that accept DET. Some accept the test but only on a supplemental basis -- students still must submit another English language test score, such as a TOEFL or IELTS score -- while some are accepting Duolingo scores on a temporary basis to accommodate students affected by testing center closures caused by the pandemic.

Others say they will accept DET as evidence of English proficiency in the same way they would accept TOEFL or IELTS. Among those American colleges that do, according to their admission websites, are Columbia, New York and Northeastern Universities, three of the top five destinations for international students.

Dewar, who formally worked in university admission offices, said she has "direct insight into some of the obstacles that financially needy international students have, especially in places like Central Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. The legacy test providers weren't always serving that population terribly well."

Another differentiator is the test's computer-adaptive nature, Dewar said.

"It is the first English language test that is fully adaptive; that’s why it's shorter," she said. "What that means is we have all these algorithms that as soon as you start taking the test can predict whether you’ll answer a question correctly and can more quickly pinpoint your abilities by only asking questions that are more relevant to your level."

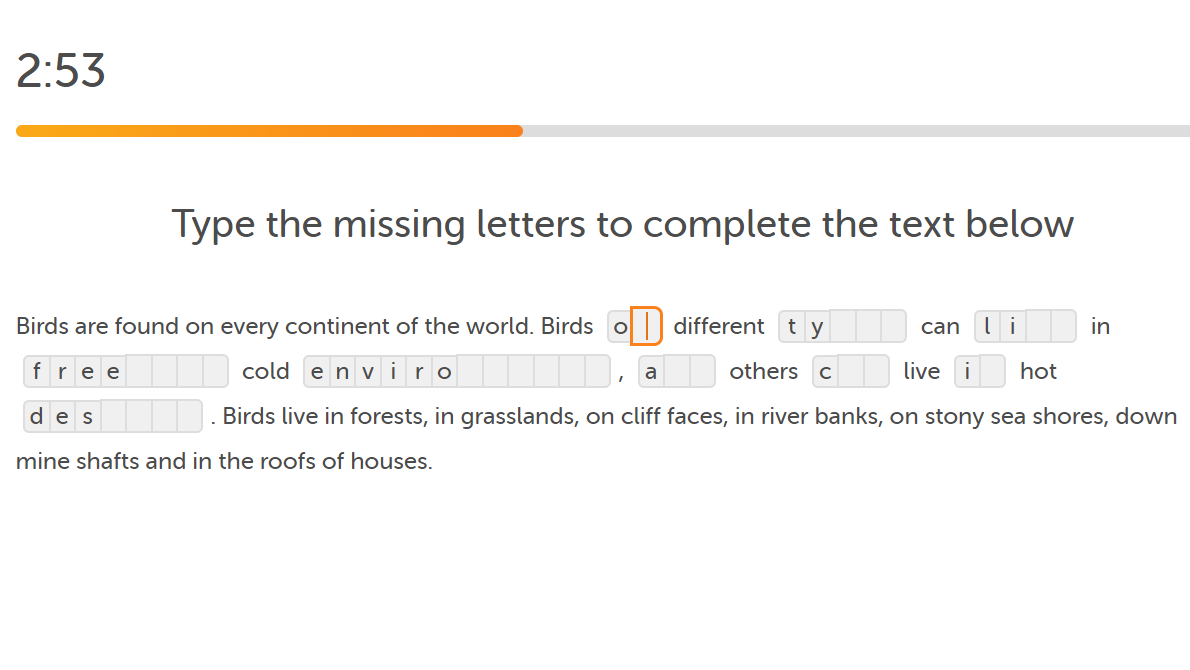

Types of questions on the DET include word completion tasks in which students identify missing letters in “damaged” words in paragraph-long passages using context clues; vocabulary tasks in which students identify real versus fake spoken and written English words; dictation tasks in which students listen to a sentence or short passage and transcribe it; read-aloud tasks that prompt test takers to speak a written sentence; and “extended” speaking and writing tasks in which test takers respond with at least 30 seconds of speech or 50 words of writing to a prompt. The DET also includes two unscored components -- a short writing sample, produced in three to five minutes, and up to a three-minute-long video interview -- sent to the colleges to which students apply.

Types of questions on the DET include word completion tasks in which students identify missing letters in “damaged” words in paragraph-long passages using context clues; vocabulary tasks in which students identify real versus fake spoken and written English words; dictation tasks in which students listen to a sentence or short passage and transcribe it; read-aloud tasks that prompt test takers to speak a written sentence; and “extended” speaking and writing tasks in which test takers respond with at least 30 seconds of speech or 50 words of writing to a prompt. The DET also includes two unscored components -- a short writing sample, produced in three to five minutes, and up to a three-minute-long video interview -- sent to the colleges to which students apply.

Elvis Wagner, an associate professor at Temple University’s College of Education, writes in a forthcoming review of the DET in the journal Language Assessment Quarterly that he can't recommend DET scores be used for university admission purposes in part because of what he describes as "its reliance on inauthentic test tasks that have little in common with the types of language uses required in university contexts."

“A shortcoming of the test is it does not seem to be assessing test-takers ability to create or comprehend discourse-level English,” Wagner wrote in a prepublished version of the article. “Obviously, in a university setting, students need to use language to comprehend and produce texts of varying lengths; they read books and articles, write papers, give oral presentations, listen to academic lectures, etc. … Even the ‘extended’ speaking and writing tasks are actually quite short, with test-takers told to respond with at least 50 words in writing, or for at least 30 seconds in speaking.”

“One of the concerns is the way the test is created -- it’s sort of a black box,” Wagner said in an interview. “You do these language-related tasks and then you get this score and they argue that score is a valid measure of someone’s ability to perform in a university setting, but if you’re going to create a test that doesn’t look anything like the language you’re going to use in that setting, they need a lot of empirical evidence showing that. The research is really minimal. It’s not peer reviewed....there’s very little of it.” (Wagner said he had no affiliations with any of the English language testing companies, though he had a research grant from TOEFL that ended about five years ago.)

(Clarification: An earlier version of this article quoted Wagner saying that Duolingo’s research on the validity of its test was not peer-reviewed. One peer-reviewed article about DET was in fact published in April. )

Dewar, of Duolingo, said the questions on the DET were designed with the limitations of an online-only test in mind. “There were two things that we had to consider in terms of the item types,” she said. “One was, was there evidence within academic literature that these item types are going to be predictive of abilities, and does it meet our security protocols? Are these item types ones that can be delivered online in a secure way and in a way that is still accessible to students? There is some criticism that we don’t have a very long essay, we don’t have a very long amount of speaking, and of course it would be great if we could spend more time with students, but we are also very conscious of how much we ask of students in terms of having access to the internet and access to a quiet space where they need to be alone.”

Duolingo has also reported that its test scores are strongly correlated with scores on the TOEFL internet-based test (ibT) and IELTS, citing correlations of 0.77 and 0.78 with TOEFL ibT and IELTS, respectively.

“That gives us a lot of confidence that the test is perhaps measuring abilities differently, but the outcome of the test and the abilities of the test taker are equally sound when somebody arrives on campus,” Dewar said.

Srikant Gopal, the head of the TOEFL program for Educational Testing Service, said that the argument that TOEFL and DET are correlated is specious because the two tests measure different things.

"Duolingo does not measure academic English communication in context," he said, while TOEFL's internet-based test "is explicitly designed to do exactly that."

Gopal said that 100 percent of the TOEFL’s content is drawn from university texts.

"TOEFL might have a reading passage and then it’ll have 10 questions" that test whether students "understand the different pieces of the passage, whether they connect to each other -- exactly the kinds of things a student sitting in a first-year classroom need to do," he said. "By contrast, Duolingo’s reading might be two lines, three lines, a short paragraph just to make sure they can read English."

Gopal said that while the accessibility argument is appealing to colleges, TOEFL is available in more than 180 countries. And for students who are willing to invest $100,000 to study overseas, he said paying around $200 for a high-quality test is not an issue.

“When you come up with messages like that and talk to U.S. universities that are already nervous about declining enrollments, some universities succumb to that marketing and they roll the dice,” Gopal said.

In a statement, IELTS said that while colleges are facing substantial recruitment and enrollment challenges, "It is important to ensure that recruitment is based on high quality, communicative language testing."

“Some lower stakes online tests don’t cover a full range of skills. They may provide a shorter and cheaper testing experience, but they can only give an indirect and fragmented sense of how much language a student knows and do not measure how well the student can use language in real-life academic and social situations. This presents risk to both the student and the higher education institution,” IELTS's statement said.

Robert Watkins, special assistant to the director at the Graduate and International Admissions Center at the University of Texas at Austin, and a former member of a TOEFL board, said he is skeptical that an approximately 30-minute test can tell colleges all they need to know about a student's English proficiency.

Robert Watkins, special assistant to the director at the Graduate and International Admissions Center at the University of Texas at Austin, and a former member of a TOEFL board, said he is skeptical that an approximately 30-minute test can tell colleges all they need to know about a student's English proficiency.

"Anything that can enhance your applicant pool and certainly an English proficiency test that is simple, quick and inexpensive is going to be attractive for institutions for getting more applicants," Watkins said. "While I get that argument … I need a product that assures me this individual is qualified to survive in the classroom, not to survive but to robustly be able to do the work that’s required of him or her. A test like TOEFL or a test like IELTS is going to give me greater assurance of that."

It is easy to see why DET would be an attractive option not just for colleges, but also for students. In its first year of accepting DET scores as evidence of English proficiency on the same basis it accepts TOEFL or IELTS scores, Northeastern University in Boston has seen a significant growth in DET submissions. Beau C. Benson, senior associate director for international recruitment at Northeastern's Office of Undergraduate Admissions, said that among freshman international applicants for this fall, Northeastern received 8,279 TOEFL results, 1,109 IELTS results and 684 Duolingo results. Among transfer applicants, the number of students submitting DET scores (272) wasn’t far behind the number submitting TOEFL (314).

Benson, who has an unpaid position sitting on a DET advisory board, said Northeastern had accepted DET as supplemental to other English proficiency tests before this admission cycle. One variable that gave him confidence to accept the test outright, he said, was the fact that students who had previously submitted scores of 75 or above on an earlier version of the test (it was graded on a100-point scale prior to the 2019 revision) earned on average a 3.36 grade point average in Northeastern's first-year writing course.

Benson said Northeastern, which has a well-regarded cooperative education program in which students are placed in full-time work settings, started accepting DET as part of a broader overhaul of its English language requirements.

"We want students to get a real education; we want to see them educated not only in the classroom but also in the real world," he said. "That is what the Duolingo test symbolizes for us. It may not be academic in the way TOEFL and IELTS are, but it assesses students in real kinds of conversation."