You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock.com/RyanJLane

College students who participated in athletics tended to fare better than nonathletes in their academic, personal and professional life during college and after graduation, a new Gallup study on alumni outcomes found.

In nearly all aspects of well-being, defined by Gallup as purpose, social, community and physical well-being, former athletes who competed in the National Collegiate Athletic Association were more likely to report they are “thriving” when it comes to health, relationships, community engagement and job satisfaction, according to the report released today. But in one category, financial well-being, former athletes and nonathletes who graduated in the last two decades reported similar levels of student loan debt, with about 20 percent of these graduates exceeding $40,000 in debt, the study found.

The study is part of Gallup’s ongoing series examining surveys of college graduates. The study split the 75,000 survey respondents into two different cohorts based on their graduation year, analyzing alumni of 1,900 different colleges and universities in the United States who graduated from 1975 to 1989 and 1990 to 2019, said Jessica Harlan, senior research consultant at Gallup, who authored the report. Some questions also examined how white former athletes and nonathletes compared to their Black peers and the impact athletics had on the success of first-generation college students.

The study is part of Gallup’s ongoing series examining surveys of college graduates. The study split the 75,000 survey respondents into two different cohorts based on their graduation year, analyzing alumni of 1,900 different colleges and universities in the United States who graduated from 1975 to 1989 and 1990 to 2019, said Jessica Harlan, senior research consultant at Gallup, who authored the report. Some questions also examined how white former athletes and nonathletes compared to their Black peers and the impact athletics had on the success of first-generation college students.

Harlan said the differences between former athlete and nonathlete outcomes are evidence of the “built-in support system” athletics provides throughout a student’s college experience, such as mentorship from peers and coaches and direct access to financial aid advisers and academic support. University leaders should find ways to replicate this structure throughout their institutions, she said.

“We know that having a sense of belonging with your peers, having a connection with the university … these are helpful and promotive for minority students, first-generation students and other underrepresented groups in academia,” Harlan said. “These are the things we find that are helping students do well in the athletic programs. How can we bring that to scale for the rest of the student body?”

Amy Perko, chief executive officer of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics, said the results of the study exemplify the primary “reasons why college sports should be preserved and strengthened as part of the educational mission.” Student engagement and mentorship, specifically from coaches, should be key goals of intercollegiate athletics, she said.

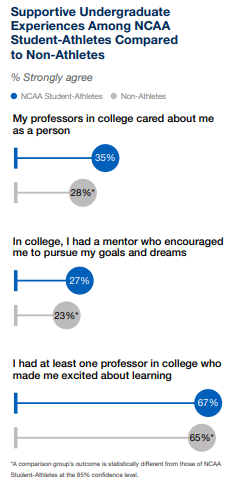

But the study also found room for improvement, including in the portion of former athletes, 27 percent, who said they “strongly agree” they had a mentor who “encouraged them to pursue their goals and dreams” during college, Perko said. These results indicate the need for athletics coaches to be better educators, a goal supported by the Knight Commission, which promotes the educational mission of college sports, she said. The NCAA and various coaches' associations have endorsed implementing more development programs for coaches, which Perko said the commission is "encouraged" by.

“Every coach should understand the importance of being a mentor and what that means for student success,” Perko said.

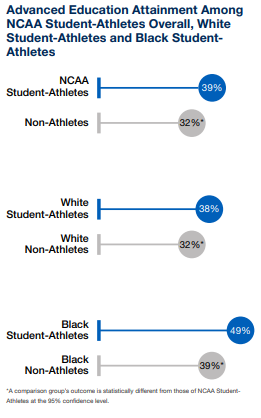

Perko said a “significant and important” result is also the Gallup finding that Black graduates who were athletes in college are 10 percent more likely to attain a master’s or doctoral degree than Black nonathletes. This could be the result of the financial support that athletes receive if they choose to compete while working toward an advanced degree and of the “enthusiasm and confidence” that athletes in particular have toward pursuing higher education opportunities, Perko said.

Perko said a “significant and important” result is also the Gallup finding that Black graduates who were athletes in college are 10 percent more likely to attain a master’s or doctoral degree than Black nonathletes. This could be the result of the financial support that athletes receive if they choose to compete while working toward an advanced degree and of the “enthusiasm and confidence” that athletes in particular have toward pursuing higher education opportunities, Perko said.

Black former athletes also reported that they had more “supportive experiences” than Black nonathletes while they were undergraduates, the study found. Forty-seven percent of Black college athletes said their undergraduate professors “cared about me as a person,” whereas 30 percent of Black nonathletes said the same. Black athletes also reported they experienced more mentorship, encouragement to pursue their goals and had professors who made them “excited about learning,” according to the study.

“It’s a positive report for the educational benefits for college sports, and it reinforces the point that we’ve tried to make over the years,” Perko said. “There’s an important role for college sports in higher education, and that role needs to be placed in the proper perspective as part of the educational mission, not apart from it.”

Former athletes are also more likely than nonathletes to have earned their bachelor’s degree in less than five years, which could be the result of the “external” motivation that academic eligibility requirements from the NCAA provide for athletes, Harlan said. Graduates who were athletes also reported a lower transfer rate than nonathletes, a metric that’s “interconnected” with on-time graduation, she said.

“The overarching takeaway is the importance of these supportive experiences from faculty, but also the system that students have to go through, the academic support structure,” Harlan said. “We know in general that’s critical. NCAA athletics programs on campuses may be one model that universities can look to for how those interact with each other.”