You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

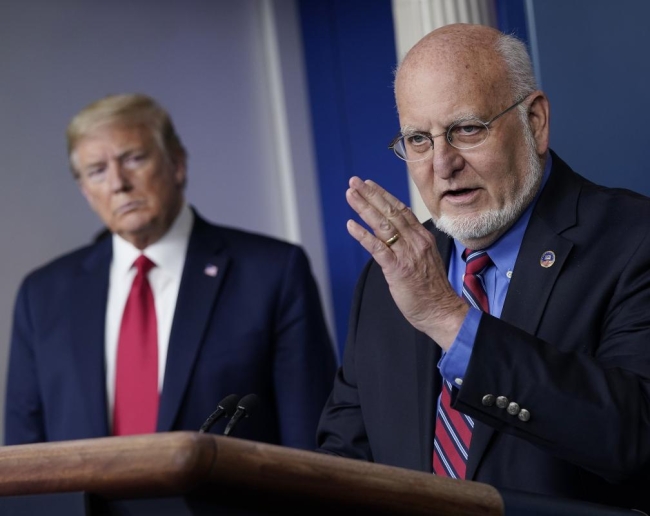

Robert Redfield (right), director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, speaks during a coronavirus task force briefing in April while President Trump looks on.

Drew Angerer/Getty Images News via Getty Images

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, college leaders have looked to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for guidance and have pointed to their adherence to CDC recommendations to assure students and employees they are reopening responsibly. But reports of political interference in the public health agency’s scientific processes over the past month are raising discomforting questions of whether and to what degree colleges can trust the CDC.

Some public health experts say the agency’s guidelines for higher education institutions have lacked specificity in some areas and left too much to the discretion of individual states and institutions, resulting in inconsistencies in approaches to opening and closing decisions and testing and quarantining protocols across the country.

“On the one hand, it is true that there shouldn’t be a one-size-fits-all solution because colleges are so different and are located in different areas and you want to allow for innovation to occur,” said Leana Wen, an emergency physician and visiting professor of health policy and management at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. “On the other hand, I think the federal government has a responsibility to do two things -- one is to have a minimum set of requirements for safe reopening and the other is to have a way to collect real-time data so that colleges can learn from one another and state and local officials can look at what is happening in real time. Both of these things the federal government has not done and really should have.”

“This is about safeguarding the health of students and faculty, but it’s also about controlling community spread,” said Wen, who formerly served as health commissioner for the city of Baltimore.

Terry W. Hartle, senior vice president for government relations for the American Council on Education, said college administrators have already determined they can't solely rely on the federal government and the CDC for guidance in any case. He noted that although the CDC hosted several calls with college leaders, agency officials were unable to answer many specific questions satisfactorily and there was no forum for ongoing discussion and exchange of information.

“I think colleges realized pretty quickly that they weren't going to get much guidance from the federal government and they would be on their own,” he said.

CDC officials did not respond to requests for an interview for this article. Public confidence in the agency has taken a hit amid a series of controversies over political interference from members of the Trump administration. President Donald Trump has publicly pushed for opening schools and for testing fewer people.

The New York Times reported last week that controversial guidance that said people who had been exposed to the virus but did not show symptoms did not need testing had been dictated by political appointees at the Department of Health and Human Services over the objections of CDC scientists; the guidance was reversed on Friday following the Times' reporting. The Times has also reported on political appointees at HHS meddling in the production of the CDC’s weekly reports on disease outbreaks and trends.

On Monday, National Public Radio reported that the CDC deleted information it had posted about aerosol transmission of the coronavirus. The agency said the draft guidance had been published mistakenly, but the deletion prompted further speculation about possible political interference.

Tom Inglesby, director of the Center for Health Security of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said the CDC has been “operating with two hands tied behind its back” because of pressure from political leadership. But he’s been heartened that incidents of apparent political interference in the work of the CDC’s career scientists have been called out and publicized.

For the most part, he said the agency’s guidance has been scientifically sound and evidence-based -- even if in some cases it doesn’t provide all the information that decision makers need. Inglesby noted for example that he would have liked to see guidance from the CDC on testing strategies for asymptomatic individuals within colleges, businesses and other organizations.

And he said that while the CDC’s published guidance on mitigation measures for higher education institutions "was well done, I think what is probably more challenging for universities and colleges is to know what the implications of [disease] incidence is in their community. If they have a huge number of cases in the state or the city per day versus very few cases, how does that impact their decisions?"

In the absence of such federal guidelines, colleges and state and local public health officials have made their own decisions about triggers for opening and closing campuses, and approaches vary widely across the country.

Just last week, the CDC issued guidance for K-12 schools with specific metrics for community case numbers and positive test rates that can be used to inform decision making about in-person learning. Inglesby said he was happy to see the document and surprised it was allowed to be published.

“It is the agency that has spent decades preparing for pandemics and infectious disease, and it has an enormous amount of talent within it,” Inglesby said of the CDC. “I think we need to recognize that it’s not operating at its full capabilities at the moment because of the political environment, but I don’t think people should turn away from it.”

“From a person who spent 16 years of their career working at the CDC, I think they have been holding back,” said Boris D. Lushniak, the dean of the University of Maryland School of Public Health and a former U.S. deputy surgeon general under former president Obama. “One can surmise: Is it political decision making? Is it that there’s a whole lot of uncertainty when it comes to COVID-19?

“Nine and a half months into this, we don’t have all the answers, nor does the CDC have all the answers, so they were somewhat reticent in terms of coming out with recommendations for higher ed,” Lushniak continued. “Am I covering for them? A little bit, yes, I am, but even under those circumstances, I think the gist from the national level was leave everything in the hands of the local, and I think that’s what the CDC was doing as opposed to being a national health science agency. I think they were rather silent on a lot of points.”

Howard Koh, the Harvey V. Fineberg Professor of the Practice of Public Health Leadership at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and a former assistant secretary for health in Obama's administration, said the absence of national coordination on the pandemic from the highest levels of government is troubling.

“From a national perspective, we had 50 states moving in 50 different directions, different criteria for reopening. We haven’t had a national mask requirement that should have been implemented long ago with the scientific evidence supporting that overwhelming. That theme has characterized all parts of society whether it’s been businesses or, in some cases, colleges and universities.”

Koh singled out the relative lack of federal guidance on testing.

"There's been so little attention to what’s been the most effective testing regimen that will control any outbreak on a campus," he said. "The strategies vary widely."

A CDC document last updated in June outlining "interim considerations" for colleges on testing recommends testing for individuals with COVID-19 symptoms and close contacts of people diagnosed with COVID-19. It makes no recommendation regarding widespread testing of asymptomatic individuals for surveillance purposes -- a strategy a number of colleges are trying -- and explicitly recommended against testing all students, staff and faculty upon re-entry to campus at the start of the fall semester, citing a lack of evidence to support the approach.

Carl T. Bergstrom, an associate professor of biology at the University of Washington, criticized the guidance recommending against entry testing in a July 14 op-ed in The Chronicle of Higher Education, writing that colleges "need to recognize that the CDC’s direction is inadequate at best and may be politically compromised as well."

Another area of contention has been about the reporting of COVID cases. A group of three Democratic senators wrote to HHS and CDC officials in August, asking officials to "ensure complete, transparent, and timely national reporting of COVID-19 cases linked to institutions of higher education."

Their letter states that "while the CDC’s guidance for colleges and universities encourages coordination with local health officials in accordance with applicable privacy laws, it does not specify a standardized format or level of detail for reporting cases or the frequency with which cases should be disclosed to the public. This lack of guidance is likely to create a patchwork of inconsistent information across states, localities, and the nation, undermining transparency and efforts to address the pandemic."

Hartle, the ACE senior vice president, pointed to broader failures of national political leadership in the pandemic response.

"Just to step back a little bit, any national challenge is met most effectively by carefully designed and consistent national leadership, but leadership by executive branch agencies has not been a characteristic of the Trump administration," Hartle said. "I think that the fact that we didn’t have consistent national leadership is a big part of why America has so bungled the response to the pandemic. Importantly, it’s not just that schools and colleges didn’t have the benefit of national leadership: nobody did."

"Nobody needed national leadership more than the schools and colleges, and nobody would have used it more extensively had it been available," Hartle continued. "It's more than just CDC … It’s obvious the CDC has been whipsawed between the scientists and the political leaders, but that’s just one agency. I would point to CDC as sort of the centerpiece of our fumbled response to the pandemic, but I think that it is not simply that CDC failed to do its job. I think that the administration didn’t really organize itself to encourage or enable CDC to succeed."