You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

ISTOCK.COM/AndreyPopov

Colleges were placing more emphasis on transfer partnerships long before the COVID-19 pandemic began this past spring.

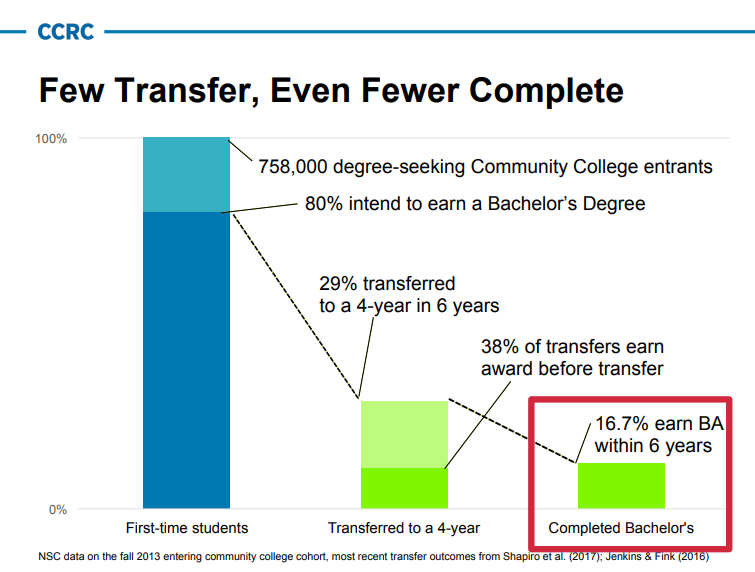

The high school population is decreasing in most parts of the country, leaving many four-year institutions with gaps in enrollment. Some experts say those colleges need transfer students from two-year colleges to survive. Community colleges, in turn, need to work with four-year colleges to prevent poaching of their students and to help students achieve their goals. Eighty percent of community college students intend to earn a bachelor’s degree, but only about 17 percent do so within six years, according to data from the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University.

The pandemic and ensuing recession leave higher education with more questions than answers on the transfer front. On the one hand, experts say, colleges need to work together to survive. On the other hand, some smaller four-year colleges are just struggling to survive, which could breed more competition than collaboration.

‘A Heightened Concern’

This also is not a great time to stand up new programs. Many states have severely cut higher education budgets, and these partnerships take both time and resources to build.

Delaware County Community College in Pennsylvania has been building its transfer partnerships since 2006. The result proves it was worth it; the college has partnerships with the state’s public universities, as well as most of the private universities within a 40-minute drive from the college, said Nora Manz, director of advising, transfer and articulations.

The college has seamless transfer with state colleges and guaranteed admission programs with several four-year colleges. It also has guides that explain for students how things articulate from the community college program to the four-year college program, Manz said.

When Manz started at Delaware in 2006, the college didn’t have a separate transfer office. She wanted to grow its relationships with other colleges to give students more options for transfer.

"One of the keys to student success is fit," she said. "What I was looking to do was provide opportunities to students across a variety of different types of schools."

It’s unknown what will happen with transfer students in the next year or so, she said. But Manz isn’t worried about increased competition from local partners for first-time students. There’s even a slight advantage. With virtual admissions and enrollment events, Manz and her team can keep an eye out for what colleges are telling students. Delaware can touch base with colleges if they don’t hear them encouraging their agreements.

"Students really look to community college advisers to help them understand the transfer process," she said. "It kind of goes both ways. If you’re a good partner, we’ll promote you. If you poach our students, then maybe we won’t share as much information."

For colleges that don’t have those relationships, Manz said, there’s probably a greater chance of poaching because of the climate.

"On the surface, it’s possible to create a relationship," she said. "But, to be honest, I wonder how you would have the time to do this."

Colleges need to align their curricula and involve relevant stakeholders, like faculty. That process alone can take months, she said. And many faculty are busy teaching in a new format due to the pandemic, or burned out from the quick pivot in the spring.

"Poaching’s not new, but we’re in an increased climate where I think that’s a concern for two-year institutions, a heightened concern," said Janet Marling, executive director of the National Institute for the Study of Transfer Students at the University of North Georgia. "Forming partnerships is really an intricate process. Right now, institutions are really focusing on survival."

Marling hopes that more colleges will create partnerships to help students transfer. But there are several factors that could lead universities to recruit community college students before they’ve completed their two-year degrees.

Transfer students are an increasingly desirable population, Marling said, especially given the already-present concerns about the high school population and new concerns about whether students are going to take time off due to the pandemic.

An extra complication is last year’s changes to the National Association for College Admission Counseling’s Code of Ethics and Professional Practice. The change stripped provisions that barred colleges from recruiting students who had already applied under early decision to or enrolled at a different institution.

"That opens up the market more and increases competition," Marling said. "Because of the recession and because institutions are struggling to stay open, at this point in time, I suspect the default action will be getting enrollment."

Community colleges have reason to be concerned, she said, especially as data show there wasn’t a significant bump in summer enrollment as some anticipated, but rather a substantial decrease.

"We’ve already seen some bad actors emerging," she said. "Others will tell you it’s important for students to have choice. However, in my experience, this was not a problem that we were needing to solve."

‘Last Affordable Route’

David Hawkins, executive director for educational content and policy at NACAC, thinks the relationships between two- and four-year colleges will likely strengthen at an accelerated pace during this time.

"While colleges over all do have to compete with each other for enrollments at a certain level, in recent years we have seen a lot more growth in the area of partnerships, particularly between two- and four-year colleges, that have helped solve enrollment problems on both ends," Hawkins said.

At the same time, he anticipates more competition, but likely not between two- and four-year colleges.

"Oftentimes, when there are economic hard times, ethics can be the first thing to go," he said, but he added, "That dynamic is not quite the same between two- and four-year colleges."

Four-year colleges are dependent on community colleges to some degree, he said.

"The four-year colleges’ incentives to work in collaboration with two-year colleges are greater than their incentive to poach two-year students," he said. "Those relationships are more important in the long term than any short-term bump from poaching."

Students’ finances could force more collaboration between colleges as well, said John Mullane, president and founder of College Transfer Solutions, a company that provides research, consulting and policy advocacy for transfer issues to colleges and universities.

"The last affordable route to a bachelor’s degree is the community college," Mullane said. "More students will end up starting at a community college."

This could force four-year colleges to collaborate with two-year colleges, he said. He’s hopeful that the current crisis will force institutions to make more progress on solving problems within transfer. Students often end up with excess credits because four-year colleges won’t put their credits toward degree or major requirements, forcing students to retake courses at the four-year college in some cases.

"If this problem doesn’t get fixed now, it might not ever get fixed," he said. "Colleges that do best with transfers will be the ones to thrive."

Mullane also advocates for lawmakers to improve transfer pathways at the state level. Some states have legislation that mandates pathways for all public institutions, but not all. And few states fully enforce transfer credit statutes, he said.

Florida is one of those states that has statewide articulation between two- and four-year colleges written into state law, said Maura Flaschner, executive director of undergraduate admissions at Florida Atlantic University.

This helps the university work with community colleges -- or state colleges, as they are called in Florida -- but their work doesn’t stop there. The university has also created enhanced two-plus-two agreements with some of its local state colleges, called the Link Program. Students receive advising from the university while they are still at the state college, as well as access to some university events and supports, said Jessica Lopez-Velez, director of transfer recruitment and the Link Program.

"Articulation agreements are in place to remove barriers and support student success," Flaschner said. "I would think that peers nationwide would be looking at such efforts."

Colleges will have to rely on these relationships more than ever now, Lopez-Velez said.

Incentives for Privates

Private four-year colleges with traditional students will also feel pressure to work more closely with community colleges, said Meagan Wilson, a senior analyst at Ithaka S+R, which provides advice and support to help institutions fulfill their missions.

"They were already seeing a pretty bad enrollment decline before COVID-19," Wilson said.

These colleges traditionally recruit high school seniors, but to survive they will increasingly have to look elsewhere. Community college transfer students could be one solution, as only one in five right now transfer to private colleges.

But they’ll be competing against public state systems, many of which have some degree of articulation agreements, she said.

The most successful cases so far have been with private colleges that came together as a consortium to create transfer agreements, such as the North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities consortium, which has 30 private colleges in a transfer agreement with the North Carolina Community Colleges system.

Private colleges can compete with public four-year colleges by accepting more transfer credits and creating better pathways, Mullane said. Right now, transfer students on average lose about 40 percent of their credits when they enroll at a private college, compared to only 20 percent when they enroll at a public college, he said.

Private nonselective institutions are "fighting for their lives," said Davis Jenkins, a senior research scholar at CCRC. He predicts this will lead them to be more cooperative with community colleges, especially because they know those students likely wouldn’t ever come to them directly.

It’s unclear whether a bump in transfer student enrollment will save any four-year college’s enrollment, though. Community college enrollment hasn’t experienced the expected bump from the recession, indicating that the crisis is hitting the most vulnerable students the hardest.

"If privates were relying on these transfer students, they might need to be worried about enrollment," Wilson said.