You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Christian Science Monitor/Contributor via Getty Images

Scrambling to attract and retain students in the middle of a historic health crisis, many colleges across the country froze or lowered tuition and fees for the current 2020-21 academic year.

The average sticker price nonetheless increased across public and private, two-year and four-year institutions. But the increases were historically low, according to the College Board’s latest Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid report, released today.

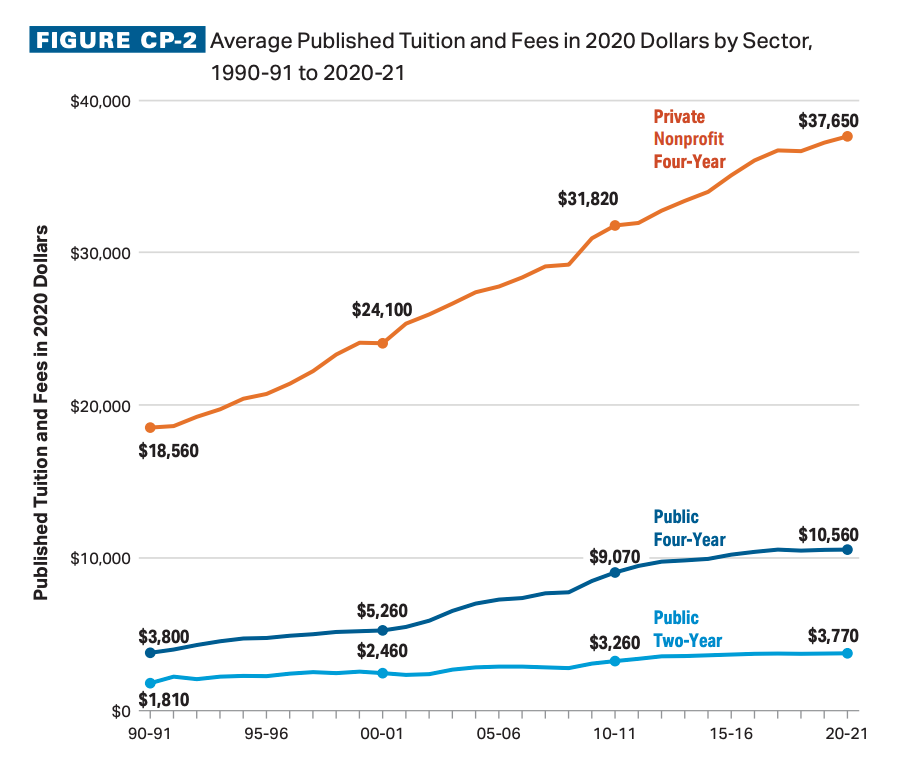

Average public, four-year, in-state tuition rates, as well as average tuition rates at private, nonprofit four-year institutions, saw their lowest percentage increases in 30 years before adjusting for inflation, said Jennifer Ma, senior policy research scientist at the College Board and co-author of the report.

“This year we’re seeing a record-high number of schools freezing or reducing tuition,” she said. “I’ve been working on this report since 2007, and I’ve never seen so many schools freezing tuition.”

The average sticker price for two-year in-district college tuition froze in 14 states. The average published price at public, four-year colleges for in-state students froze in 10 states, according to the report.

Still, average tuition and fees ticked upward nationally this fall, as they have for years. The report shows average full-time undergraduate sticker prices for all institutional types increased by between 0.9 percent -- for public, four-year out-of-state tuition -- and 2.1 percent before adjusting for inflation.

Average published in-district tuition and fees for the 2020-21 academic year at public, two-year colleges is $3,770, which is $70 higher than in 2019-20. The average public, four-year in-state rate is $10,560 this academic year, $120 higher than in 2019-20. For out-of-state students, average tuition and fees came in at $27,020, a $250 jump from last academic year. At private nonprofit four-year colleges, the average listed tuition and fees total $37,650, a more than $700 increase from the previous year.

Experts can’t point to a sole reason why college is consistently getting more expensive. Some highlight the new amenities colleges offer to woo students -- see: climbing walls, lazy rivers -- while others say it’s to make up for declines and meager increases in public education funding. Still others believe it’s administrative bloat and colleges’ drive to increase top salaries to draw in talented faculty members and administrators.

Beth Akers, senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, has argued that college pricing is not transparent in the same way as is pricing for most goods and services. This allows institutions to routinely increase their prices and face few penalties from the consumer. True comparison shopping is virtually impossible.

“We know that a lot of students don’t understand how the pricing works. They don’t realize how much they’re paying or even how much they’re borrowing,” Akers said. “That inefficiency in the market may be allowing institutions to get away with increasing their prices year after year, whereas if people were more familiar with what expenses they were paying and have a better sense of the value they were actually getting out of that purchase, we’d probably see that inflation rate start to decline.”

She likened selecting a college to house hunting.

“It would be like if I were shopping for a house, and I had to apply and be approved for a mortgage before you tell me how much that house costs,” Akers said.

The College Board’s annual Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid report pulls from the latest available data on tuition and fees, net college costs, student federal aid, education borrowing and student loan debt, state and federal higher education funding, and more.

Only the tuition and fees figures reflect the early financial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most of the other data in the report are from the previous academic year, which ended in the summer of 2020, just as the pandemic was beginning. Next year’s report -- and possibly reports for years after that -- could better show the full impact of the pandemic on higher education enrollment, funding, pricing and borrowing.

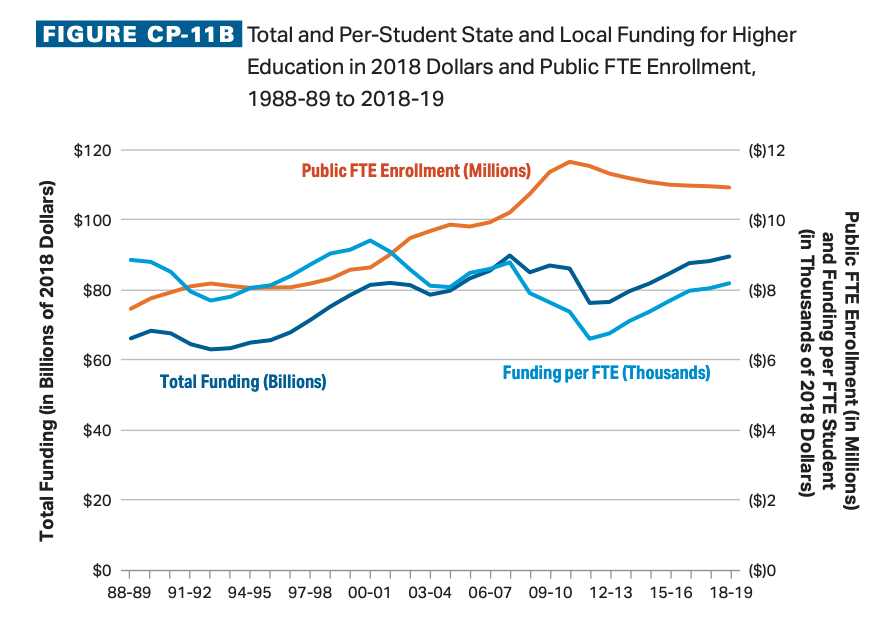

State and local funding for higher education increased in 2018-19 for the seventh consecutive year, following four years of declines, the report shows. The increase reflects a slow recovery following the Great Recession. After adjusting for inflation, 2018-19 total local and state funding levels almost match the levels in 2007-08, just before the recession hit. But due to enrollment increases, per-student funding remained lower than it was in 2007-08.

These public funding numbers have yet to reflect the financial effects of the pandemic on state budgets.

“I would absolutely anticipate states having to make cuts in the coming year as they deal with revenue shortages and as they deal with the economic downturn from the coronavirus,” Akers said.

Some states have already cut funding for higher education, and Ma expects that other states may follow suit. During the Great Recession, enrollment increased dramatically, especially at community colleges and for-profit colleges, Ma said. The state funding decline was coupled with a spike in college enrollments, which had a big effect of driving down state funding per student.

“This recession is a little different,” Ma said. “We know that many states have cut funding, but also at the same time, enrollment is declining as well, so we’re not really sure what’s going to happen to state funding per student.”

Community college enrollment appears to have been particularly hard hit so far during the pandemic, according to early data recently released by the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. Community college enrollment has dropped 9.4 percent, according to figures from the research center covering about half of postsecondary institutions as of Sept. 24. First-time enrollment at community colleges dropped by almost 23 percent. Undergraduate enrollment at all institution types across the country was tracking 4 percent lower than it was last fall.

Undergraduate student borrowing has declined by 37 percent in the past decade, according to the report. The 2019-20 academic year marked the ninth consecutive year of decline in education borrowing. Students and parents borrowed a total of $102 billion last year, compared with $134.1 billion (in 2019 dollars) in 2010-11.

One reason could be that older would-be students had been returning to the workforce in recent years, and older students typically borrow more than traditional college-age students, said Sandy Baum, nonresident senior fellow at the Urban Institute. Baum used to co-author the annual College Board pricing and student aid reports.

“As the economy recovered, a couple of things happened,” Baum said. “Some people who were going to go to college because they couldn’t get a job got jobs, so community college enrollment fell, and for-profit enrollment fell a lot.”

Institutional grant aid is also increasing, Baum said, meaning students may have to borrow less. Over the past 10 years, total institutional grant aid for undergraduate students increased by 72 percent, the report shows.

Among those holding student debt, 45 percent of all federal student debt is held by only 10 percent of borrowers, the report shows. Borrowers within that 10 percent owe, on average, $80,000 or more. Just over half of borrowers with outstanding education debt owed less than $20,000.

Student Aid Buys Down Net Prices

The vast majority of students don’t pay the full sticker price. The College Board’s report includes data from recent years showing how much financial aid went to students that year and what average net prices -- the difference between published prices and average grant aid -- students actually paid.

Since the 2009-10 academic year, first-time full-time undergraduates at public two-year colleges have received enough grant aid on average to cover their tuition and fees. But those students still need to cover an estimated average of $8,860 in room and board expenses after grant aid is applied, plus an average of $5,700 in books, supplies, transportation and other related expenses. At public four-year institutions, first-time, full-time in-state students paid an average net tuition price of $3,230 in 2020-21. Similar students at private, nonprofit four-year colleges paid a net price of $15,990 in 2020-21.

During the 2019-20 academic year, undergraduate and graduate students received $242 billion in student aid grants from all sources -- Federal Work-Study, federal loans and federal tax credits and deductions. Over the past two decades, average grant aid per full-time-equivalent undergraduate student more than doubled in 2019 dollars from $4,560 in 1999-2000 to $9,850 in 2019-20, the report states. For graduate students, average grant aid per full-time equivalent student increased by 44 percent from $6,420 in 1999-2000 to $9,260 in 2019-20.

During the 2018-19 academic year, 87 percent of first-time, full-time undergraduate students at private nonprofit four-year colleges received federal, state or institutional grant aid. At public four-year colleges, three-quarters of first-time full-time undergraduates received federal, state or institutional grant aid. At public two-year colleges, that number was 71 percent.