You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Samford Hall at Auburn University

Getty Images/Raymond Boyd

Alabama's Black population is 26 percent of the state. Auburn University's Black population is about 5 percent.

When a group of Black Auburn alumni came together over the summer to find a way to have an impact on diversity matters at their alma mater, this statistic concerned them most.

The group, called the Coalition of Black Alumni, was driven by the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, both Black people, and the subsequent protests and movement against racism and police violence in the U.S.

"We were all independently looking at diversity at Auburn with its enrollments, recruitment and scholarships," said Dewayne Scott, a member of the group advocating for better diversity efforts and a 1995 alumnus. "We decided to come together, and that culminated in us having a meeting with the provost."

The coalition has had several meetings with university leaders, but they still feel Auburn's efforts are insufficient. Jay Gogue, president of Auburn, created a task force in the summer to address issues of diversity, equity and inclusion. Four of the five student members who regularly attended weekly meetings quit in November, citing frustration with how slowly the process was moving.

Inside Higher Ed requested an interview with the vice president of inclusion and equity or other staff and provided questions to Auburn. Inside Higher Ed previously arranged an interview with the vice president of inclusion and equity, but she never answered the phone or responded to subsequent emails.

In response to interview requests, a university spokesman provided a copy of the letter the university sent to the concerned alumni and a copy of board resolutions to rename two areas on campus and a statement from Gogue:

"Auburn continues a very thorough process to study issues related to equity and inclusion. Our philosophy has been to take action at the right time and for the right reasons after all facts are gathered, input is received and a process that can hold the test of time is implemented. We have had more than a dozen meetings with our stakeholders -- including African-American students, faculty, staff, alumni and others -- to gain insight and facts," he wrote. "The Auburn Board of Trustees during its past two meetings has taken significant actions regarding this important issue, including adoption of a new policy on removing names from buildings and structures as well as action to recognize leaders who have been at the forefront of equity and inclusion. Every university in America should continually find ways to strengthen its environment and culture so all students, faculty, staff and supporters may reach their fullest potential. Auburn is no exception. Today, we are a university with strong leadership from people of many races and backgrounds. We continue to work to make our university the best it can be for everyone we serve today and in the years to come."

‘They Don’t Have an Answer’

The Coalition of Black Alumni is not satisfied with the university's statements and letters. They want action, they said.

"This task force is just one of many that has been set up over the years," said Barbara Wallace-Edwards, a 1979 alumna. "Auburn has a history of every time there is a major issue arising, they set up a task force to address those concerns and recommendations are made to the university, but what we have seen is that those recommendations are never implemented."

Auburn created a similar task force in 2015. Its recommendations included creating clear recruitment and retention strategies for students of color and investing more in need-based scholarships, two demands of the coalition.

A progress report from the university states that departments and colleges across the university created recruitment plans. But Black student enrollment has not improved. In 2011, the oldest available data on Auburn's website, the number of new, first-time freshman Black students was 268. This fall, it was 157.

Total enrollment for Black students decreased from 1,935 in 2011 to 1,624 in 2020. Black students now make up about 5.3 percent of the student population at Auburn.

The report also states the university is working to increase enrollment of Pell Grant recipients to address the recommendation to increase need-based aid. The percentage of Auburn students who received Pell Grants has decreased since the 2010-11 academic year, from 18 percent to 13 percent in the 2018-19 academic year.

The university currently has a need-based scholarship called the Provost Leadership Undergraduate Scholarship (PLUS) Program. It is available to any freshman, though priority is given to first-generation students, those with greater financial needs, Alabama residents and those who have a "diverse background." It provides $2,000 annually for up to three years. Undergraduate tuition and fees at Auburn total $5,898 for Alabama residents, and room and board costs $6,889.

The coalition asked for several changes from the university in a meeting, including:

- Increase Black freshman enrollment by 25 percent per year starting next fall.

- Increase the award amount for the PLUS Scholarship to at least $5,000 each year.

- Increase the number of Black students who receive the PLUS award by 50 percent.

- Fire leadership in the Office of Inclusion and Diversity.

- Rename buildings associated with slavery or the Ku Klux Klan.

- Increase the number of Black faculty and staff. (Auburn had 65 Black faculty members in the fall of 2019, out of a total 1,426 faculty. Slightly less than 12 percent of all faculty and staff were Black.)

In response, Auburn has taken several actions, such as designating 10 percent of its scholarships for students with financial need, using the Common Application for admissions, guaranteeing admission to all valedictorians and salutatorians in Alabama, and having recruiters visit every high school in the state.

But when members of the coalition asked how those changes would directly impact Black student enrollment, leadership didn't have an answer, they said.

"If you’re at 5 percent enrollment today, five years from now with these initiatives, where do you expect to be?" said Rick Rodgers, a 1980 alumnus. "They will not answer the question. Because they don’t have an answer."

‘Symbolic Acts’

Auburn seems to be falling behind on diversity compared to other universities. It's located near cities, like Selma and Montgomery, with large Black populations, yet it enrolls few of Black students. Black enrollment at the University of Alabama also doesn't come close to mirroring the state's population, but it's still 10 percent -- about twice the Black student enrollment at Auburn. The University of North Alabama is 12 percent Black, and the University of South Alabama is 22 percent Black.

The coalition isn't asking Auburn to reach ridiculous numbers. But it is asking the land-grant university to represent the state it's supposed to serve.

"A lot of the times, I’ll look at my roll sheet and we’ll have more students from Chicago, Boston or Boulder, Colo., than we’ll have from the local communities around us," said Keith Hébert, an associate professor and public history program officer at Auburn. "Some of that is we’re trying to become a robust research university. But there are talented African American students in our region that we don't seem to be putting effort into recruiting."

Another reason is that Auburn doesn't create a friendly atmosphere for Black students, Hébert said. For example, other institutions in the state worked quickly to change building names after the protests of the summer. But Auburn has clung to a state law that prohibits universities from changing names on buildings more than 20 years old unless they go through a process to get a waiver.

Another reason is that Auburn doesn't create a friendly atmosphere for Black students, Hébert said. For example, other institutions in the state worked quickly to change building names after the protests of the summer. But Auburn has clung to a state law that prohibits universities from changing names on buildings more than 20 years old unless they go through a process to get a waiver.

Auburn recently announced it is renaming the Graves Ampitheatre and Graves Drive, both named after former governor Bibb Graves, who was endorsed by the Ku Klux Klan. The task force also recommended a policy for renaming buildings.

But this work was done years ago. A committee was created to review the history of names on campus, but its recommendations weren't carried out before the state's law against changes was enacted.

More recently, history faculty created a map detailing each building name that has a racist history. For example, Samford Hall, which has offices for university administration and the president, is named after William J. Samford, a Confederate soldier who was in favor of secession. One of the campus's fraternities, Kappa Alpha Order, sees Robert E. Lee, a commander of the Confederate army during the Civil War, as its spiritual founder.

"Symbolic acts do mean something. Creating a more inclusive environment really necessitates taking serious a world that Auburn has created for itself -- a world that has enshrined white supremacists," Hébert said.

Auburn is also renaming the student center after Harold Melton, the first Black president of the Student Government Association at Auburn and the current chief justice of the Georgia Supreme Court. But alumni feel this is a political move, as Melton is a conservative who could appeal to donors upset about the focus on diversity.

"If you’re going to name it after a Black person, why not the first Black student?" Rodgers said. The university won't do that, he said, because it originally denied graduation to Harold Franklin more than 50 years ago.

A Dual World

On the surface, Auburn is a friendly and polite place, Hébert said. But there's a hidden world that taints the university's culture.

"Sometimes, when you get in groups of people who think they’re among likeminded people, they’ll start saying racist things," he said.

Hébert, who is white, showed up early to an off-campus event once. He overheard white people talk about how African Americans moving to the city of Auburn are ruining the public school system. A half hour later, a Black man showed up to the event and had a congenial talk with those white people, Hébert said.

Hébert doesn't think the administrators of the university are in that dual world. But some people with influence -- donors, trustees or lobbyists -- might be.

Several students, as well as the Coalition for Black Alumni, who spoke with Inside Higher Ed said they have been told or heard about how donors are influencing the university's resistance to real change.

Elizabeth Devore, a Ph.D. student and instructor at Auburn who was one of the student members who left the task force, believes the administration coddles donors. While on the task force, she felt as though some administrators were trying to gaslight them by reading letters from alumni who were upset about efforts to improve diversity during meetings.

One alumnus wrote that Auburn should "not be in the business of 'diversity and inclusion.' They are in the business of education … Anything that is based on 'diversity and inclusion' is, in fact, RACIST" (emphasis from the source), according to an email provided to Inside Higher Ed. The alumni accused the university of pandering to "utter nonsense" and says the letter writer's grandchildren will not attend the university because of these issues.

After months of meetings where the students on the task force felt they weren't being heard, four out of the five student members who regularly attended weekly meetings quit. In a recording of the meeting where members quit provided to Inside Higher Ed, students said they felt members of the task force were gaslighting them, weren't empathetic and weren't making real progress toward the goals. (Alabama law allows people to record meetings with the consent of one party.) They felt the task force was a performance. Students also discussed the meeting with the coalition. The coalition was told the meeting was with the full task force, but it was just with some administrators and staff -- the students were not aware of the meeting at all.

"It has been exhausting to see how undervalued and how overlooked Black students, Black alum, Black graduate students continue to be treated," said one of the students in the recording.

Devore, a white woman who was the only former student member who felt comfortable speaking on the record, feels like administrators are just waiting for current student activists to graduate and move on.

Devore and other student members were further disheartened to see the minutes from the meeting following the one where they resigned. Task force members discussed the students' resignation. Several said they were pained to hear the students were upset. But several also said it seemed the students came into the task force challenging it. One member said he followed up with the students to meet with them, which the students confirmed. But the others either didn't want to reach out to the students or didn't push the group as a whole to do so.

Devore said she and other students were appalled to read the comments.

"I see the problems, and it’s heartbreaking to know the university that has been a home to me for nearly all of my adult life is so painfully and willfully ignorant. Auburn administrators know the problems; I know that with certainty. I spent over four months speaking directly with administrators who say they want change, that they're willing to invest, but there is a limit and exceptions," she said. "I understand that change in culture takes time. But after watching the numbers for African American student admissions and enrollment continue to decline four years after a universitywide climate study that provided an analysis of the problems, I and everyone else who cares about Auburn should question administrators and demand better."

Students Speak Out

Devore and the other students plan to continue working in their campus organizations to improve the university.

She has been at the university since she was an undergraduate student. As she's grown, she's tried to become an active ally for people who are different from her and may face discrimination. This fall, she sent an email to her students saying she supported them in light of the police shooting of Jacob Blake, a Black man, in Wisconsin.

One of her students wrote back saying Devore is not paid to tell them her thoughts. The student said they are proud to be white and that recognizing race is problematic, because God makes everyone perfect.

"That's the sentiment I hear -- you should just focus on being kind," Devore said. "But that hasn't gotten us anywhere."

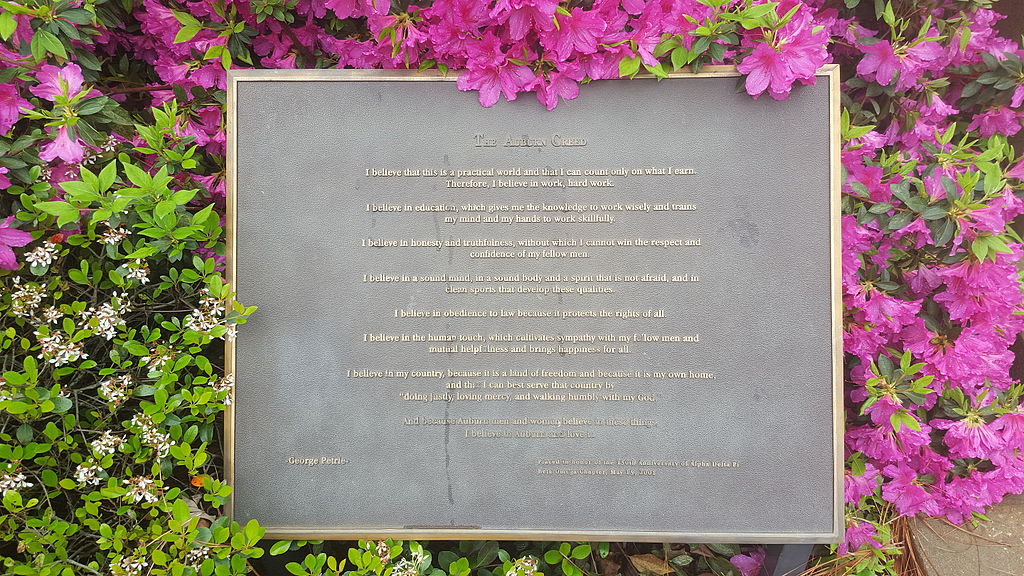

Other students and alumni pointed to this unwillingness on the part of some Auburn students, faculty or alumni to recognize white privilege. Many repeat the line of focusing on the Auburn Creed, Devore said.

The creed was written in 1943 by George Petrie, a longtime administrator and professor at Auburn. It's said to embody the spirit of Auburn, and it seems to be a common refrain among the university community.

I believe that this is a practical world and that I can count only on what I earn. Therefore, I believe in work, hard work.

I believe in education, which gives me the knowledge to work wisely and trains my mind and my hands to work skillfully.

I believe in honesty and truthfulness, without which I cannot win the respect and confidence of my fellow men.

I believe in a sound mind, in a sound body and a spirit that is not afraid, and in clean sports that develop these qualities.

I believe in obedience to law because it protects the rights of all.

I believe in the human touch, which cultivates sympathy with my fellow men and mutual helpfulness and brings happiness for all.

I believe in my Country, because it is a land of freedom and because it is my own home, and that I can best serve that country by "doing justly, loving mercy, and walking humbly with my God."

And because Auburn men and women believe in these things, I believe in Auburn and love it.

"We were not at the table when the Auburn Creed was written," Wallace-Edwards said. "Until Auburn is representing the demographics of this state, I as an alum am not going to be happy."

Auburn has a history of students committing hate crimes or saying inflammatory things. A noose was found in a residence hall in 2019. Leaders of the White Student Union have made racist remarks and invited Richard Spencer, a neo-Nazi, to speak on campus. The Instagram account Black at Auburn details the microaggressions and outright racism students experience every day. One student said the first thing they were asked as a freshman was, "What sport do you play that got you into Auburn?" Another wrote that a student said to them, "There's a difference between [N-word] and Black people, and you're neither of them."

Jailin Sanders, president of the Black Student Union and a senior at Auburn, was a junior and resident assistant when the noose was found on campus. He felt there was a lack of urgency from the university. He didn't get updates for four days after it was found, despite having to answer to and care for residents.

When Sanders first got accepted to Auburn, he took the questionnaire to be matched with a roommate. He later received a Facebook message from someone who knew his potential roommate. It was a group chat with a screenshot of his Facebook page, calling Sanders an "N-word for Auburn."

"I didn't know what to do. I was taken aback," he said. Thankfully, housing let students do room swaps, and his potential roommate requested one. But it was a rude awakening to the new environment he was entering.

"Coming to Auburn definitely was a cultural shock and an adjustment for me," he said.

At a Black Student Union meeting, a white student stood up and said the first time she saw Black people was when she came to Auburn. Sanders and his friends are often one of a handful, or fewer, of Black students in a class. Administrators need to listen to this qualitative feedback, instead of just focusing on quantitative data, he said.

Sanders has been encouraged by some administrators. Some are regularly attending the Black Student Union meetings.

"I feel like we are in a good space. We’re heading in the right direction. We have to put a little gas to it, but we’re in the right direction," he said.

Not all students agree, though. Catoria Sharp, director of the events committee for the Black Student Union and a junior at Auburn, said the Black Student Union is one of the few spaces at the university where she feels she can be herself.

Not all students agree, though. Catoria Sharp, director of the events committee for the Black Student Union and a junior at Auburn, said the Black Student Union is one of the few spaces at the university where she feels she can be herself.

Students will also stare at her or roll their eyes at her when she wears T-shirts or masks that say things like "unapologetically Black." Some white students have also tried to touch her hair. A public speaking professor once gave her a C because she chose the topic of how Black History Month was originated, and the professor thought it was biased.

"Auburn is definitely not for the weak, especially if you're a Black student," she said. "You have to be able to stand your ground with some people."

She's also upset that the university hasn't changed the racist names of some buildings, like Wallace Hall, named for former governor George C. Wallace, who fought to prevent the integration of the state's schools and universities.

"That goes to show that you worship money more than you care about the safety of Black students," she said.

Other students reported similar experiences of microaggressions or seemingly unconscious racism. Arianna Jones, director of community and equity for the Black Student Union and a junior at Auburn, has had classes where she was the only Black student, and other students would always choose her last for group work. Sororities won't give her pamphlets when they're on campus trying to recruit people. A professor once asked students to pretend they were slaves on the Underground Railroad and imagine how they would escape.

"I felt like Auburn was competitive, and I’m not afraid of a challenge. I think my degree will be worth it," Jones said. "But I do feel like things are harder for me than for my friends at other colleges."

Shecoria Akins, assistant director of the event planning committee at the Black Student Union and a sophomore at Auburn, loves Auburn. But she's often reminded of the class and cultural differences between herself and her peers.

When she was involved with the Student Government Association, everyone assumed Akins and the only Black male student wanted to date each other. Some of her peers in student organizations spout racist thoughts on social media.

She wants Auburn to do better, especially with scholarships. All of the Black students she knows are middle or upper middle class. Auburn has told alumni that it legally can't focus scholarships on specific groups.

"I just don’t think if you’re poor and Black you’re going to come to Auburn," she said.

Brandan Belser, assistant director of community and equity at the Black Student Union and a sophomore at Auburn, grew up in predominantly white spaces his whole life. But Auburn was still a culture shock, he said.

"The first thing I realized coming to Camp War Eagle [a first-year summer orientation program] was the experience of being at Auburn was going to be an experience of silence," he said. "A lot of Black students realized the only way people will tolerate us at Auburn is if we're standing in the back of a picture."

Belser is disappointed in the task force. He'd almost rather not have it all if it isn't going to make real change, he said.

"I don't think that they are interested in making any lasting change to the precedent that’s been established," he said.