You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

FatCamera via Getty Images

Students who learned entirely online during the fall semester said they received a slightly poorer quality of education than those who had in-person instruction, according to a new poll released Tuesday by Gallup, the polling company, and the Lumina Foundation, a nonprofit organization that advocates for equity in postsecondary education.

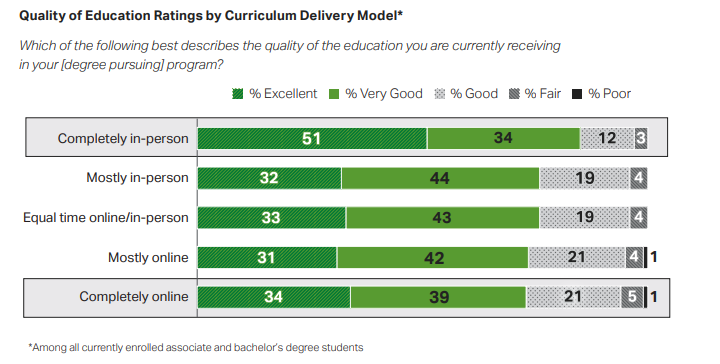

The poll found that about three-quarters of students over all rated the quality of their education “excellent” or “very good” amid the disruptions of the coronavirus pandemic this fall, but this largely positive outcome dropped off somewhat when surveyed students were separated by learning modality. Eighty-five percent of students whose curriculum was “completely” in person said their education quality was “excellent” or “very good,” while 71 percent of those learning “completely” online said the same, a report about the findings said.

Dissatisfaction was highest among students whom the pandemic “forced online” when under normal circumstances they would take all in-person classes, according to the report, which polled about 6,000 current students -- nearly 4,000 of them seeking bachelor’s degrees and about 2,000 pursuing associate degrees -- during late September and early October. Nearly 22 percent of student respondents were taking classes “completely” or “mostly” in person when they were surveyed, while about 60 percent attended classes “completely” or “mostly” online, according to poll results.

Jonathan Rothwell, principal economist at Gallup and a contributor to the report, said the poll results show that students prefer in-person instruction, and shifts to online instruction by some colleges damaged students' perceptions of academic quality. This is a positive finding for traditional residential colleges, which can expect students will generally want to return to campus when it’s safe to do so, he said.

“The in-person experience is perceived as higher quality by students, and having that taken away has been a blow,” he said. “The fact that there is that clear preference for in-person learning and it’s regarded as a loss and real harm for students to be forced online should be reassuring for those whose careers and livelihoods depend on students being on campus.”

But Kristine Young, president of State University of New York at Orange, a Hispanic-serving community college about 60 miles north of Manhattan, said that an overwhelming majority of students on her campus were satisfied with their switch to mostly online learning during the fall and even preferred learning remotely. Young said a recent survey of students at the college found that 83 percent planned to enroll in classes in the spring, which she believes is in line with the Gallup and Lumina finding that 72 percent of associate degree-seeking students nationwide had an “excellent” or “very good” learning experience in the fall.

“Most of them were welcoming of being remote,” she said. “It was like a one-two punch, seeing the national data set and ours … What’s happening is quality, and it is fiction that remote education or online learning can’t possibly be as good as looking at some learned person standing in front of a room. That myth being so pervasive right now is so damaging.”

Young did note that some SUNY Orange students had difficulty balancing family and financial responsibilities with remote academic work. Many students were uncertain about daycare and the shifting plans of the New York public school systems, which were “a persistent pull” away from college work.

Chris Sinclair, executive director of FLIP National, a first-generation and low-income student advocacy group, said Gallup’s quality-of-education findings did not reflect the conversations he’s had with students in the organization’s 23 campus chapters. About half of students surveyed by Gallup were low income, and 47 percent were first-generation students, Rothwell said.

Sinclair said these students are struggling with outside factors that might not be defined by “quality of education,” such as lacking a study space, working more than one job to make up for family members' employment loss or dealing with professors who aren’t sympathetic to their home or financial situation, all of which can impact students’ learning outcomes. He questioned whether Gallup's sample was adequately representative of first-generation and low-income students because it yielded such positive overall results about the quality of education during the fall.

“We’re talking to students where there’s a lot of struggle,” Sinclair said. “A lot of what we’re hearing is less about professors’ ability to teach … First-generation students don’t question their ability to do the work. But a lot of times when first-generation students struggle, it’s not merit, it’s circumstances.”

Parts of the survey did address student circumstances, including the finding that one-third of students said in the last six months they considered discontinuing their college education, citing COVID-19, emotional stress and the cost of attendance as the top reasons why they considered not taking classes, the report said. Additionally, about half of students said COVID-19 will “likely” or “very likely” hinder their ability to continue through college moving forward, according to the report. Rothwell said these results should “raise alarm bells” for colleges.

“This could be a real problem,” he said. “Even if [colleges] haven’t faced the full brunt of students stopping, at this point in the pandemic there’s a real possibility it could happen this semester or early next year.”

Black and Hispanic students were more likely than white students to say they might not be able to complete their degree due to the pandemic, which is reflective of the “financial blow” that COVID-19 has had on communities of color and working-class people, Rothwell said. Fifty-six percent of Black and Hispanic students pursuing bachelor’s degrees and 60 percent pursuing associate degrees said it is “very likely” or “likely” that the pandemic would negatively impact their ability to continue college, compared to 44 percent of their white peers pursuing bachelor's degrees and 52 percent pursuing associate degrees, the report said.

These findings about students discontinuing college are “worrisome,” especially for institutions without strong public funding or substantial internal resources, Carlo Salerno, vice president of research for CampusLogic, a student financial success company, said in an email.

“Even if COVID ends tomorrow, the impact on family finances is likely to persist for many months, if not years,” Salerno said. “Many smaller, nonpublic colleges may not have the financial room to lose the students they have, nor cover the cost of recruiting new students to replace them … In some cases COVID may be shining a light on larger challenges related to access and affordability that we can’t, and frankly shouldn’t, ignore.”