You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The University of Maryland at College Park will name two new residence halls after Black and Asian alumni who broke racial and ethnic barriers at the university.

University of Maryland at College Park

The founding and early history of the University of Maryland at College Park are steeped in racism and slavery -- a legacy of many land-grant institutions in the United States that is becoming more widely known and openly discussed. But students, faculty and staff members at the college have also recently been confronting the ongoing and modern threat of white supremacy.

The campus was shaken in 2017, when Sean Urbanski, a white UMD student, murdered Richard Collins III, a Black Bowie State University student and lieutenant in the U.S. Army who was visiting a friend who attended the university. Urbanski was sentenced to life in prison last month, and many believe racial animus played a central role in the killing; Urbanski belonged to a white supremacist Facebook group, The Washington Post reported.

Honoring Collins with a scholarship in his name and establishing UMD and Bowie faculty-led social justice programs to combat intolerance were among President Darryll Pines’s first initiatives when he assumed leadership of the College Park campus in July 2020. Pines also launched several other antiracism-focused initiatives that touch various parts of campus, including the 1856 Project, which will research, examine and disseminate information about the university's history with slavery and racism, and the naming of two new residence halls after the first Black and Asian students who attended the university while it was still segregated and largely unwelcoming to nonwhite people.

The namings are “mostly symbolic,” Pines said in an interview. But they are also significant: it’s the first time in a century that campus residence halls at UMD will be named for individuals, as they are traditionally named for counties in the state of Maryland, according to a university press release.

The one exception to this tradition is a dorm named after Charles Benedict Calvert, a founder and acting president of the university who was himself a slaveholder, Lae’l Hughes-Watkins, a university archivist and co-lead of the 1856 Project, said in an email. The project is named for the year the Maryland Agricultural College (now UMD College Park) was founded and is part of Universities Studying Slavery, a broader group of institutions nationally that are researching how their institutions are connected to or benefited from enslaved people.

“During the 150th Anniversary of the University of Maryland in 2006, there were students and faculty and other members of the UMD community who were surprised to learn of some of the stories related to the institution’s founding,” such as Calvert’s slave ownership, Hughes-Watkins said.

“Some of the earliest presidents were members of the Confederate Army, even high-ranking members of the Confederacy … But where is this history incorporated into the institutional onboarding and orientation and ongoing education of our community?” she said.

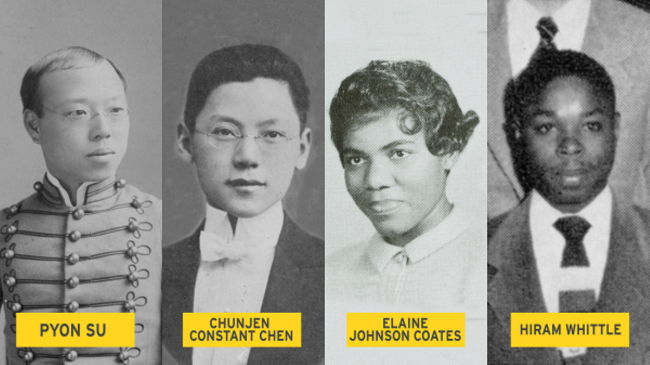

To contrast these troubling figures in the university’s past, one of the new residence halls will be named Johnson-Whittle Hall, after Hiram Whittle, the first Black man to be admitted to UMD and Elaine Johnson Coates, the first Black woman to receive her undergraduate degree there, the release said. Pyon-Chen Hall will honor Pyon Su, the first Korean person to receive a degree from UMD or any American higher education institution, and Chunjen Constant Chen, the first Chinese student to enroll at the university, the release said.

Karsonya Wise Whitehead, founder and director of the new Karson Institute for Race, Peace and Social Justice at Loyola University, Maryland, a private Jesuit institution in Baltimore, said even if namings are symbolic, they have meaning at institutions of higher education and in American society more broadly.

“In this country, naming something matters. It matters that if you are attending a university named after a leader, that they’re a civil rights leader versus a slaveholder,” said Whitehead, a professor of communication and African and African American studies at Loyola. “The only way to undo racism is to unravel the thread and replace it all. If the naming of a building is where it starts, let’s start there.”

Pines sees the namings of the new residence halls as a way to “set the tone” for students coming to UMD under his tenure and to demonstrate that the university is committed to being a welcoming place for students, faculty and staff members of all backgrounds. The assurance was especially vital as the university underwent a change in leadership amid ongoing protests for racial justice after the killing of George Floyd and other unarmed Black people during summer 2020, he said.

“Some of the events of the past 170 years of this great institution had not been addressed appropriately,” Pines said. “I wanted to recognize the historic history made by trailblazers … to embrace the culture of diversity and inclusion at our institution and to honor those who broke barriers.”

Watkins-Hughes said in her email that Floyd’s killing brought renewed attention to issues of racial injustice, particularly at higher education institutions, that students have been engaged in for a long time but UMD is now fully embracing. This type of “inward reflection” will help the university move forward with new initiatives for inclusivity and equity on campus, she said.

The project will allow the campus “to face these histories, unpack them, draw the relationships between these narratives of the past and how they have shaped the landscape we navigate today, all the way up to the murder of [Collins] … up to the insurrection that occurred a few miles from the University of Maryland on January 6,” she said referring to the recent attack at the U.S. Capitol. “Hopefully, the work we are charting will help us confront our past, our present, and plot out our future armed with an honest understanding of who we have been and imagine an inclusive and equitable future.”

As part of further efforts to embrace and promote inclusiveness, students and other members of the university also have a new way to formally propose institutional name changes, thanks to a systemwide policy that went into effect in November. Pines and other system presidents will receive and consider name change requests that have historical and factual rationales and broad enough support in the form of a letter and petition, according to the new section added to the system’s naming policy.

The decision to rename “should not erase an important aspect of the university’s past, and where possible, education about and reinterpretation of the name in order for the university community to deepen its understanding about its history may be a reasonable alternative to removal,” the policy says.

Saba Tshibaka, an organizer for Black Terps Matter, a UMD student group, and other students started gathering signatures at the beginning of the year for one of the first formal name change petitions under the new policy. The petition, signed mostly so far by students, requests that the university’s administration building be renamed. Immediately before Pines became president, the building was named after Thomas “Mike” Miller Jr., a longtime state senator and president and advocate for public funding to the university, who died Jan. 15.

But Tshibaka and other students also remember Miller for his disparaging comments about the city of Baltimore, which he called a “goddamn ghetto” in 1989. Their letter to Pines about the name change said that some of Miller’s policies and comments about Black communities in Maryland and opposition to same-sex marriage in 2011 were “detrimental” to Black and LGBTQ people.

“It is one thing to idly bear witness to racial inequity but wholly another to choose to act in an anti-racist way,” the letter said. “To anyone who truly values anti-racism and anti-bigotry, this is a moment for action … To honor someone like Mike Miller says that it’s okay to be racist, homophobic, and transphobic because not only will you be appreciated, but you will be celebrated.”

Tshibaka said student opposition to Miller’s name on the building was communicated to administrators in June, when the change was announced. She is concerned that even if the petition is successful, it will take several months to be evaluated in a university committee. But Pines emphasized the importance of engaging in a “very careful” process that evaluates the entirety of a person’s background before disassociating from them.

“You can be, on one side, very emotional about someone’s name, because you’ve only looked at a bit of their background,” Pines said. “Often, you'll find out that some individuals made mistakes early on, but later in life, they recover from those mistakes … We should look at the full embodiment of the person’s life. That is a deliberate process that does take time and requires deep research. I’d say to students to be patient and to trust the process.”

While the naming of buildings can send a message of inclusivity on campus, Pines said a new onboarding program for all incoming students, faculty and staff members will ensure more substantive improvements to the university’s culture. Additionally, all people who learn, teach or work at the institution will be required to take part in the new TerrapinSTRONG training program, which includes university history, expectations and values, diversity and inclusion goals, and information on sexual harassment prevention, Pines said. The program is currently being offered as online modules and sessions over Zoom by some individual colleges and schools at the university.

First-year students will have additional antiracism and sexual identity education in their required general education courses. The goal of these efforts is to help students and others on campus become more knowledgeable, understanding and respectful of each other's diverse backgrounds, Pines said. Some of the TerrapinSTRONG onboarding sessions were already rolled out during the fall 2020 semester.

But Pines expects it will take a long time for the new programming and other administrative task forces and commissions that are examining other campus policies, such as biased police practices, to take root at the university.

“It’s a broad base of work that we’re embarking on, and granted, it'll take years before we arrive at a much happier place,” he said. “But I believe the times that we’re living in requires it.”