You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Protesters march at the University of Florida before a Donald Trump Jr. speech at the Gainesville campus in 2019.

Paul Hennessy/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

In the six weeks leading up to the 2020 election, a majority of students said they were reluctant to discuss politics, race and other controversial topics in class settings, according to a new report from the Heterodox Academy, a nonprofit group that promotes open inquiry and viewpoint diversity at colleges and universities.

Over all, 60 percent of 1,311 undergraduate students who responded to an online survey developed by the Heterodox Academy said they were hesitant to talk with classmates and professors about certain issues, including politics, race, religion, sexual orientation and gender, the report said. All the students surveyed were between 18 and 24 years old. They attended four-year institutions in every region of the U.S. and shared responses between Sept. 22 and Nov. 3, according to the report’s methodology.

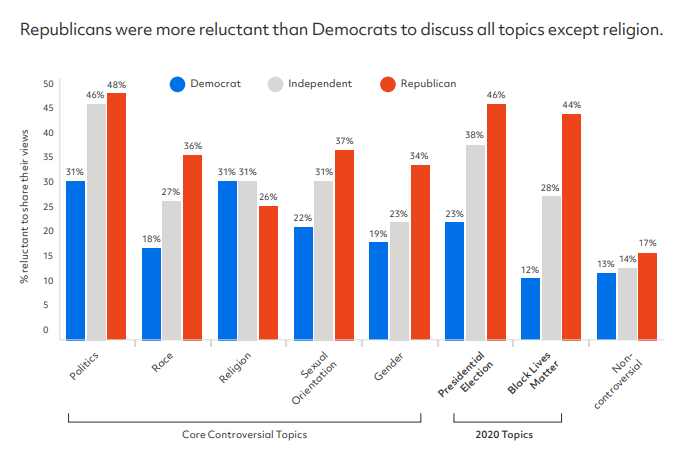

The report found significant and “alarming” differences between Republican and Democratic students’ comfort speaking about current political events happening during the fall 2020 semester, said Melissa Stiksma, a contracted data analyst for the Heterodox Academy and author of the report. She noted that 44 percent of Republican students said they were reluctant to speak about the Black Lives Matter movement, versus 12 percent of Democratic students. This discrepancy was consistent when students were asked about discussing the presidential election -- 46 percent of Republican students felt reluctant to speak about the election, compared to 23 percent of Democratic students, the report said.

“It’s so concerning, on both sides, that Republican students are not part of the conversation on some of the biggest issues,” said Stiksma, who is also a psychology doctoral student and graduate research assistant at George Mason University.

The report’s findings represent a continuing trend in higher education seen across multiple student surveys over the last several years that some college leaders and civil liberties advocates have identified as a growing free expression crisis. Conservative students have consistently reported that they feel more hesitant than liberals to share their points of view on prevalent societal and political topics, and some fear that their self-censorship may erode free and politically diverse discourse on college campuses. However, not everyone agrees with characterizing the issue as a crisis and with viewing it through a primarily political lens.

Though the issue is routinely framed based on students’ political leanings, students across the board are feeling uneasy speaking up about their views, said Lori White, president of DePauw University, a private liberal arts institution in Indiana. Young people have a heightened fear of being ostracized for what they say, especially on social media, said White, who is a member of a recently launched Bipartisan Policy Center task force for college leaders on campus free expression. Students are also introduced to an array of diverse people and perspectives on college campuses, and they may feel uncomfortable speaking on topics or about identities that are new to them, she said.

“Students are afraid, perhaps, talking about how they really feel about something, and afraid that it might not be a popular opinion on their campus,” White said. “I think we need more respectful dialogue. I think we need to have more of an ability to give people grace when they say or do something offensive.”

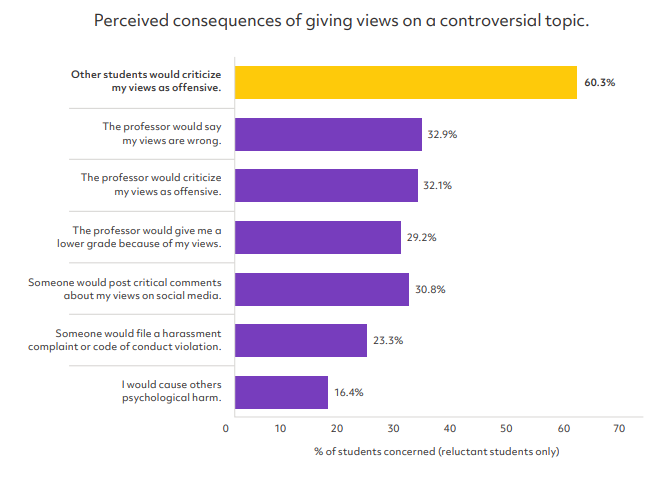

In the Heterodox Academy survey, students were primarily concerned about their opinions being criticized as offensive by their peers -- more so than their professors. Sixty percent of students who were reluctant to speak about at least one of the controversial topics said they worried classmates would find their views offensive, compared to about one-third who feared their professor would say “my views are wrong” or “would criticize my views as offensive,” according to the report.

In the Heterodox Academy survey, students were primarily concerned about their opinions being criticized as offensive by their peers -- more so than their professors. Sixty percent of students who were reluctant to speak about at least one of the controversial topics said they worried classmates would find their views offensive, compared to about one-third who feared their professor would say “my views are wrong” or “would criticize my views as offensive,” according to the report.

Lara Schwartz, director of American University’s Project on Civil Discourse and an expert on campus free speech, said the Heterodox Academy report took a deficit approach about the state of free expression on campuses, suggesting that professors and college leaders should do more to encourage students with potentially offensive views to speak up. But in Schwartz’s view, a more effective way to promote free speech would be to teach students that offending someone and learning from it can be a good thing.

“My recommendation is, find ways for teachers and schools to build a kind of resilience in students where if they’re told, ‘You just hurt me or offended me,’ they’re able to breathe through it and think, ‘This isn’t the worst thing that’s happened to me,’” she said. “What if you worked on having less marginalized students be more resilient to the response from others that their ideas aren’t liked?”

Students across many different demographics expressed discomfort talking about certain issues, typically when they were in the “majority demographic” or didn’t identify with a group impacted by the discussion, Stiksma said. For example, 30 percent of white students surveyed said they were reluctant to discuss race, compared to 17 percent of Black students and 19 percent of Hispanic and Latinx students, the report said. Similarly, 40 percent of atheist students were reluctant to speak about religion, versus about one-quarter of Christian, Jewish and Muslim students, according to the report.

The reluctance to speak among majority groups, especially as it pertains to race and the Black Lives Matter movement, could be viewed as positive or negative, Stiksma said. White students might be recognizing that it’s not appropriate for them to speak for or over students of color on issues of race. But at the same time, the racial justice movement has called for white people to be actively antiracist and address systemic racism, she said.

“It’s unfortunate because it’s probably a time when people should be saying things out loud with thoughtfulness and without ignorance and the intention to harm a group of people,” Stiksma said.

Based on the open-ended comments students submitted with the survey, Stiksma said that those hesitant to speak on race were worried about saying something “slightly out of step” or making a “not as informed” comment, “rather than something that’s truly malicious.” She noted that as the United States grapples with its history of racism and ongoing racial issues, it would be beneficial for students to disagree with one another and be introduced to new perspectives, rather than avoiding the discussion altogether.

There is a way to discuss politics and race with mindfulness and without offending those of a different background, said Kaitlyn Reynolds, a senior at Georgetown University and vice president of operations for Gen Z GOP, a national group of young Republican students. Reynolds, who is Black and supported President Donald Trump, said she is often reduced to either her skin color or her political leaning before discussing politics with other students.

“I love being a person of color, a Black woman, but I also don’t identify with the same views as every other Black woman in this world,” she said. “There’s a happy medium to go about such conversations … Don’t make assumptions about somebody’s beliefs based on their skin color. Find articulate ways to formulate questions, and do your own basic research before asking questions.”