You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The Workforce Talent Educators Association plans to accredit institutions based on workforce outcomes.

WTEA

Workforce Talent Educators Association, a newly formed organization seeking to certify that colleges and universities do a particularly good job of preparing students for the job market, joins a crowded field. Quality Assurance Commons and other similar outfits have offered much the same service for decades—and have sometimes struggled to find institutions interested in doing the work required to earn their stamp of approval.

But there are reasons more of these efforts are cropping up now. College enrollments have been steadily declining. Increasingly, students and their parents are focused on whether often-hefty tuition bills will yield good jobs after graduation. A report released in October documents the problem: 16 percent of high school graduates, 23 percent of workers with some college education and 28 percent of associate-degree holders earn more than half of what workers with a bachelor’s degree earn, according to the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

To Jennifer Dirmeyer, the themes underpinning the Georgetown center’s findings demand that institutions more clearly establish a return on investment in terms of career preparation. In September, Dirmeyer and partner Joseph Kozusko launched WTEA to serve as what she calls a “nonprofit quality-assurance body and association to drive excellence in career-building education.” The group has visions down the road of providing formal accreditation of institutions or programs, but the focus now is on giving institutions a way to prove they help students succeed in the job market.

Dirmeyer, a former economics professor at Ferris State University, said her experience there led her to ask questions about how institutions prepare students to find jobs.

“I just started really thinking about the whole incentive structure that people are operating in in postsecondary ed and thinking about the accreditation system … and how all of that is really shaping incentives that schools are working under, and that none of them are really focused on student workforce success,” Dirmeyer said.

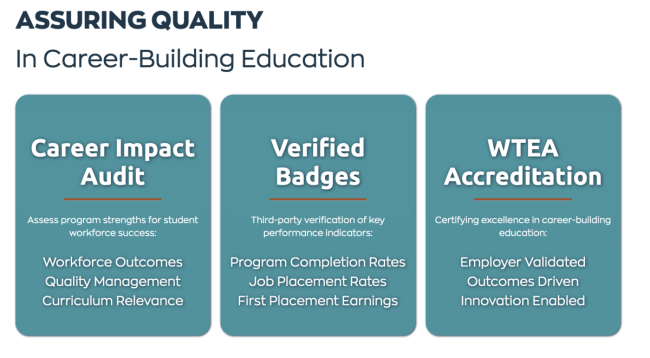

To be certified by WTEA, Dirmeyer said, an institution will submit an educational or training program, at which point WTEA will complete an assessment of the program’s “student workforce outcomes,” “quality management processes” and “curriculum relevance” to determine if the program meets requirements in all areas. If a program is successful, it will be publicly recognized with WTEA certification indicating it provides an excellent career-building education.

“We do not have specific requirements or even an opinion about how an educational program delivers its curriculum or designs its student supports,” Dirmeyer said. “We are completely focused on determining whether or not a school is able to demonstrate, through objective outcome measures, that it is preparing learners for workforce success … We are building expertise in assessment—not in program design or delivery.”

She likened the effort to the Distance Education Accrediting Commission, which focuses on “one function within a school”—specifically, a distance education focus. Unlike DEAC, WTEA’s approval won’t carry with it any formal federal authority to award financial aid. Instead, Dirmeyer said, her organization is focused on creating a “market advantage” for its members.

Dirmeyer said WTEA could one day seek recognition from the U.S. Department of Education as a programmatic or institutional accreditor for providers focused exclusively on workforce-preparation programs. But it is focused now on what it calls a “career impact audit,” an assessment and evaluation tool that institutions can use for either continuous improvement or to demonstrate excellence in workforce outcomes, quality management processes and curriculum relevance. Dirmeyer said WTEA’s Standards Advisory Committee will take these quality-assurance categories and create benchmarks that programs must meet to be certified.

Dirmeyer said she has looked to the success of Texas State Technical College as an inspiration for her work (TSTC is a founding member of the WTEA).

Mike Reeser is chancellor of TSTC, which was chartered by the Texas state Legislature in the 1960s as a two-year system focused on meeting employers’ needs in the state. He said that given its mission, TSTC always has been laser focused on the employment outcomes of its graduates. A decade ago, TSTC voluntarily tied its budget and state funding to graduates’ job-placement rates and salaries—and it has thrived.

“We don’t get any public support for progressing people through the programs,” Reeser said. “A hundred percent of our public support is earned when our students get a job, and the extent to which their earnings exceed minimum wage drives an aggregate value, and we get paid a certain percentage of the value.”

Reeser said in his view, WTEA is responding to a need in the market for accreditors to add new indicators ensuring quality in workforce development.

“For schools like [TSTC], whose first purpose is to produce prosperous professional outcomes for our students, if that’s your first goal, then that must be an integral plank in the accreditation process,” Reeser said. “I believe that the students will demand it from many institutions … A liberal arts college will need to be able to demonstrate to the students how the study of classic knowledge will indeed yield a better professional outcome.”

Brooke Buffington, director of Elon University’s Student Professional Development Center, said Elon has sought to distinguish itself as a liberal arts institution focused on student career readiness and has developed what Buffington calls an “experiential learning model.”

Buffington said she will need to learn more about WTEA’s quality-assurance process in the coming months, but she is open to considering pursuing it.

“There’s always opportunity to close the gap between education, higher education and employers, and to create more synergies in the work that we’re doing,” Buffington said.

Experts questioned whether Dirmeyer will be able to pull off what many say will be a difficult pursuit—one that other groups have struggled with.

Quality Assurance Commons was founded in 2016 and focuses on “proficiencies employers say are most needed, which candidates often lack, and are the hardest to find,” according to its website. QA Commons has engaged 34 institutions, evaluated 83 programs and certified 17 since its founding.

President Mason Bishop said it is not easy for organizations like QA Commons and WTEA to generate demand.

“No organization has a lack of capacity problem if the demand can’t be generated,” Bishop said in an email. “In this work, in order to generate demand, having an accreditation or certification process is not enough, in my opinion. The value proposition is showing educational institutions directly how faculty and students benefit.”

Bishop said that soon after taking over at QA Commons seven months ago, he realized it lacked incentives for instructors to participate in its program-certification model. Under Bishop, QA Commons has instituted a three-step process to get certified. It is also creating a badging system for students to show technical skills and credentials to employers.

Bishop said QA Commons is now focused on helping education programs “embed employability skills into their existing curriculum.” Predicting that WTEA will need to develop a “tangible product or outcome,” Bishop said QA Commons has experienced pushback from institutions hesitant to go through “‘one more accreditation process.’ This is one reason we are sticking with program certification rather than ourselves moving to accreditation.”

Michael Horn is a veteran in this terrain; more than a decade ago, he developed what he called the quality value index to measure postsecondary institutions. He later founded a nonprofit—since acquired by Jobs for the Future—focused on education quality outcomes and how to standardize them. The standards touch on learning completion, salary growth, placement and learner satisfaction to measure quality for different types of programs.

“We built it in a way that it can be super workforce oriented in short-term programs, but also in a way that had enough breathability in the standards that a liberal arts college or fine arts colleges could find a way to use it to express the value they believe they impart for students,” Horn said.

Horn said the WTEA effort reminds him of other initiatives, which he described as voluntary associations where institutions want to distinguish themselves by having gold standards for outcomes.

He said accreditation is the federal government’s proxy for quality today, but there are weaknesses to the existing accreditation system. Horn said he hopes efforts like WTEA’s help shift the conversation to be more outcomes based.

“For federal funding, nine out of 10 of the indicators are based on inputs,” Horn said. “There are not agreed-upon standards, and what are we looking for for outcomes. And as a result, accreditation does not really stand for the seal of quality approval that learners perhaps think that it does, so I think efforts like this are important to change that narrative and just shift us to hydroplane.”