You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

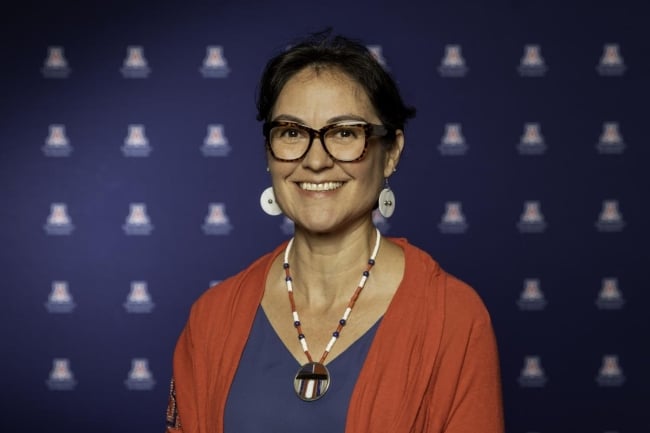

Shelly Lowe, chair of the NEH

Photo by Chris Richards

Shelly Lowe spoke with Inside Higher Ed this week about what it is like to be the first Native American chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities, the federal agency charged with supporting research and education in the humanities.

Lowe has a history of scholarship in the field of Native American studies from working as executive director of Harvard University’s Native American program, as assistant dean and director of the Native American Cultural Center at Yale University and as a graduate education program facilitator for American Indian studies at the University of Arizona. Before she was nominated to the chair position by President Biden in October 2021 and confirmed by the Senate in February this year, she was appointed by President Obama to the NEH’s advisory board, the National Council on the Humanities, in 2015.

The following is a transcript that was edited for length and clarity.

Q: How does your Native American heritage inform your leadership style and your approach to studying the humanities?

A: I think that was a question that I had to stop and reflect upon myself. The first time I ever thought about it was when I got onto the National Council for the Humanities and we were in our council meeting with then chair Bill Adams, and he asked us at what point did we understand that humanities was important in our lives? People would go around and talk about, well, I read this book or I went to a lecture. I said, I didn’t have one of those moments. I said I’ve always known that it’s just the way that I grew up and the way that you were supposed to kind of understand and think about things in the world from a very specific kind of cultural aspect. It was just always a part of what you were taught and what you did.

There is no one moment where you think, “Oh, that’s humanities!” It was living it every single day. Just being reinforced every day as you are continually taught cultural teachings, as you were continually kind of working through understanding what it means to be Navajo living on the Navajo reservation. So it was just always a constant for me. It’s a part of everything we do, and it’s instilled in us from the very start. However your culture or your family teaches you, what kind of person you’re supposed to be and how you’re supposed to live in the world and the ideals and the goals that you’re supposed to have in life. Native culture is connected for everybody. We just haven’t thought about it that way.

Q: Why do you think we’re not taught to think about it that way?

A: I think that there are just other aspects that were more important, right? So not thinking about the natural world in exactly the same way, and our relationship to the natural. I think we are coming back to it. I think there’s a lot of focus now on how do we live in the world and how do we live responsibly in the world so that we can continue to live in the world? And I’m talking about the natural world, the environment. We’ve got away from that and focused on other things—development, industrialization, technology—and we started to forget about the natural world and our connection to it. But I definitely think we’re coming back to it.

Q: Do you think it’s important right now to view humanities as adjacent to other fields of research?

A: I think the humanities is the basis for all things. I used an analogy one time—one of our first Navajo surgeons, we talk a lot to our Native youth about going and becoming lawyers, becoming doctors. The health field is a really big draw for a lot of our youth—they want to go and become doctors and nurses, physicians, because they want to come back and help the health disparities on the Navajo reservation and help heal the health issues that we have. And you can do that and you can be a doctor. But the unique thing is you’re always going to be a Navajo doctor. You’re always going to think about that work in a very specific Navajo frame of mind. Which means understanding that sometimes what we do with medicine, practical medicine, is going to be complemented with what you have to do with ceremony and more traditional healing aspects. I think everybody has that cultural worldview that they come in from.

Q: Can you talk a bit about your previous roles in Native American studies?

A: I’ll start at University of Arizona, because that’s where I was introduced to American Indian studies. Once I took an American Indian studies course, you start to understand why things aren’t good. That was the first time I was taught those very specific historical aspects of policies that the government had enacted laws, rules, regulations, how reservations are set up. I was never taught that before. When I kind of got that larger view, it’s like, oh, I get it now. That makes sense. And now I see that there are avenues to be able to work through and address these issues and be part of creating solutions and making things better. It was kind of like, how come I never was taught this before? And the worst part was 95 percent of the students on campus weren’t being taught this.

Q: What do you think it means for people who are studying Indigenous cultures to have someone like you in a position at the NEH?

A: I am hoping it brings a spotlight. One, to the fact that we have Native studies. I think one of the things about putting an individual who has experience like I do, who has come out of Native studies, who has worked in Native studies, who has worked in Native support programs within higher education, it actually helps people understand that these things exist. There’s so many people that don’t even know that these kinds of programs exist. There’s always this assumption they exist because there’s a problem with Native students and they have to have these programs to help Native students get through college. It’s not about everybody learning from these programs and getting resources and support from these officers.

People are starting to pay attention, like, oh, wait, there are these programs that are doing really great things. They’re teaching not just Native students, they’re teaching entire communities on campus. There really is a value to the entire campus and the entire population, and not just for Native students, and I think people forget that fairly often.

Q: How do you want to leave this place better off than you found it? What are some things that you are really focusing on as your objectives?

A: I came into the position with some groundwork having been done in terms of the agency and the kind of administrative foundation for the agency. So when I was a council member, we didn’t get a lot of information about where we weren’t funding grants. When I came in, there had already been a discussion about an Office of Data and Evaluation. And I said, yes, please can we put that in? How do you do work within an agency if you don’t have an Office of Data and Evaluation that really can tell you where you’re having an impact and, more importantly, where you are not having an impact and help you try to figure out why that is not happening? The agency has had this before; we just haven’t had it in more recent years. We really need to be data-driven in the work that we do.

Q: What are some specific provisions of the application process that you think could be changed to reach into underrepresented communities?

A: One of the things our division directors are looking at is how do we put in place some smaller grant sizes that really can help us reach out to smaller organizations, organizations with fewer administrative staff sizes and get them connected to us? Have them apply if we can fund them, then they have a relationship with us. Very often when an organization has a relationship with any agency, they will come back later. They’ll build upon whatever it is they’ve proposed, and then they’ll come back again. Or at least they have, then, this connection to all of the other resources and programs and offices and organizations that NEH is connected to. It does broaden kind of the resource level and feel that they are able to connect to after that.

Q: You recently announced $31.5 million for 226 humanities projects nationwide. Can you give me some of the highlights?

A: I think one of the ones that I’m really excited about is the Latino poetry project. This is very, very large. This project got a special chair’s grant or designation, so this is going to be a national project that really is focusing on Latino poetry. There are going to be events across the country. It’s going to be the first time that the kind of anthology and a pulling together of Latino poetry over time. It’s gonna come together. It’s gonna be cool!

[The Latino poetry project referenced by Lowe is a project by the Library of America, a nonprofit publisher founded with money from the NEH in 1979, in partnership with the National Association of the Latino Arts and Cultures. The project received almost $850,000 from the NEH to create an anthology of 400 years of Latino poetry, starting in the 16th century and continuing to the present day. The project will also host cultural events at 75 public libraries nationwide.]

Q: You mentioned in a prior interview for Humanities Magazine that you were hiring a chief diversity officer and creating an office of outreach. What are these roles going to bring that has never existed before and when do you expect to have them filled?

A: These should be filled later this year. We’re starting with the Office of Data and Evaluation, and we’re in the process now of trying to identify and hire somebody to direct that office. That’s step one of understanding internally our work. The second part of that for the director of outreach is, you know, when we do have a sense of where are we not reaching? How do we start to build those relationships? How do we start to reach those communities and encourage them to think about NEH as a place to apply for their amazing and outstanding programs? The director of outreach will be the individual that will really do the legwork. So really trying to get out into those communities, find out what their needs are, find out what has kept them from thinking about NEH in the past, find out what kind of hurdles that they’ve had if they’ve applied before and start to work with communities to help us figure out how do we make our grant lines much more equitable to smaller organizations, to rural organizations, to community colleges, to HBCUs? Those organizations that just don’t have the grant-writing staff that large institutions that we’re familiar with generally have and are doing this on a full-time basis. That person will be kind of the, what I’m calling our recruiter. The person who is really going to be out there speaking for us.

The chief diversity officer will be internal, and it is the part of doing this work and making the agency and our work more equitable [that] is making sure that we as staff within the agency are understanding exactly what doing equitable work looks like. How do we create a foundation for every single staff member to be thinking about equity, inclusion, diversity, accessibility in the work that we do? So the person that comes in as our chief diversity officer is going to ensure that we as staff and administrators in the agency are trained, that we have the information, that we are understanding the populations that we are trying to reach, and that we understand that even internally that we are doing things in a manner that does bring in accessibility across all of the areas of the agency that does have and thinks about inclusion.

Q: What can we expect from the NEH in the future?

A: I expect that more small organizations that haven’t had NEH funding will be applying and will be announced as receiving grants. This will bring more attention to what I hear all the time as untold stories of our country. One of the things I said is that we’re such a great and wonderful country, but we don’t tell all of our great and wonderful stories all the time. Or we are not telling them in a national way. We kind of focus on the negativity more often than I think that we should. We have such wonderful, rich, diverse cultures in this country, and there’s so much that we can learn from each and every one of those communities that I think is part of the work that we’re going to be putting out there. Might start with some Latino poetry (laughs).