You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Marquette students who protested at convocation in August now face sanctions for Code of Conduct violations.

TMJ4 News Milwaukee

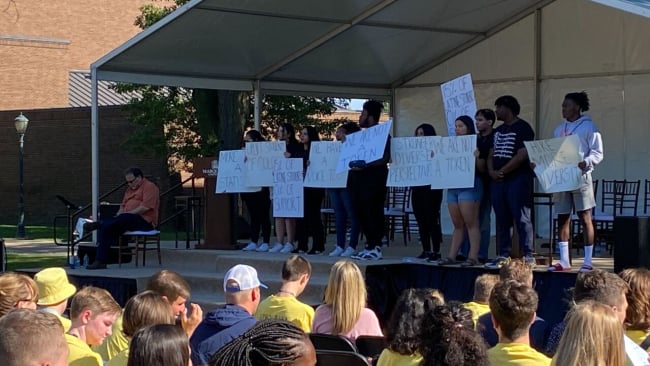

Marquette University’s incoming class found an unexpected scene at the New Student Convocation in August: a group of student protesters took to the stage to decry what they saw as a lack of resources and institutional support for students of color. The protest interrupted the festivities and prompted the administration to cancel the event.

University officials charged 10 students of color—whom they identified from photos and videos of the protest—with “disorderly or disruptive conduct,” among other violations. But the repercussions didn’t end there.

At the conduct hearing set to determine their punishment, the protesters were subjected to what Marquette professor Julissa Ventura likened to a criminal interrogation and received penalties—including probation and a $300 fine—that she and the students argued were disproportionate to their actions.

Now the incident has inflamed tensions on campus, sparking renewed criticism of the administration’s approach to free speech. Some students and faculty argue that the harsh punishments show that Marquette’s administrators care more about quieting dissidents than about supporting students of color.

‘Intimidation Tactic’

According to Ventura, a professor of educational policy and leadership who has been advising the 10 sanctioned students, the conduct hearings in early September were inconsistent with any she has witnessed before. They did not follow uniform guidelines, she noted; some students appeared alone, while others were questioned in pairs. And the university official running the hearings took a hostile stand from the beginning, demanding to know who had organized the protest at convocation, Ventura said, and warning students there would be consequences for the group if they didn’t name names.

That, “to me, is an intimidation tactic,” Ventura said. “And students were visibly shaking and sobbing.”

Lynn C. Griffith, a spokesperson for Marquette, told Inside Higher Ed in an email that conduct hearings “are an educational discussion, not an interrogation” and that they are designed to “help form students of character and integrity who are able to understand the consequences of their behavior for themselves and others.”

Ventura said the hearings were far from educational.

“I’m a professor, and I can tell you that if a student is crying in my class, that student is not learning anything that I’m talking about,” she said.

(Through Ventura, the sanctioned students declined to speak with Inside Higher Ed, out of fear that speaking with the media could negatively impact their situation.)

As punishment, all 10 students were required to pay a $300 fine, write an apology, participate in community service and develop educational programming about the university’s demonstration policy. They were also placed on probation, and three received suspensions in abeyance, meaning the suspensions will only go into effect if they commit additional conduct violations.

The fines came as an especially hard blow to the students, some of whom financially support themselves, Ventura said. She also noted the students are unsure whether they can fulfill all the penalties by the end of the semester.

“These are students who are student leaders, who are in classes, who are working—some of them work multiple jobs,” she said.

In late September, the students appealed the sanctions on the grounds that they were inconsistent and unfair.

University administrators disagreed and on Wednesday ruled that all sanctions would stand—except for the fines.

The probation ruling remains the most upsetting to the students, Ventura said, because it means they are no longer in good academic standing and must step down from their student leadership positions, in accordance with Marquette’s student organization policies.

“They’re just, at this point, really sad and really disappointed at the ways in which the university has treated them. These are students who have always gone above and beyond for the university,” Ventura said.

Controversial Demonstration Policy

The students chose to demonstrate at convocation to protest a lack of institutional support for students of color, citing the understaffed Office of Engagement and Inclusion, which currently has four open positions, and the Urban Scholars program, which they also say is understaffed, as two of the resources the university has neglected. Marquette, a private, Jesuit university in Milwaukee, has touted this year’s freshman class as the most diverse in its history, with 30 percent of the class identifying as students of color.

Initially, the protesters stood silently in front of the stage, holding signs with messages such as "Stronger Diverse Perspectives" and "We are Not a Token." But then the audience, composed of incoming students and family members, started jeering at the protesters, Ventura said.

When university administrators walked onto the stage without acknowledging the protest, that's when the protesters decided they needed to mount the stage to make their statement.

According to a message from Marquette provost Kimo Ah Yun, they then occupied “the New Student Convocation stage, shouting into their portable sound system, and preventing a planned, celebratory moment for the Class of 2026 and their families. While multiple senior university leaders repeatedly attempted to de-escalate the situation, students continued to occupy the stage and yell profanities, resulting in the cancelation and rescheduling of New Student Convocation.”

In addition to disorderly or disruptive conduct, the 10 students were charged with failing to comply with directions from university employees, violating university policies (in this case, the demonstration policy) and “condoning” other individuals’ conduct violations.

Marquette’s demonstration policy—which, as of Sunday night, was the only student policy not publicly available online—has been subject to scrutiny since it was first introduced in 2019, due largely to a provision that requires most protests to be cleared by administrators before they take place.

Many members of Marquette’s faculty opposed the policy when it was rolled out. In an open letter published in The Chronicle of Higher Education in 2019, more than 100 faculty members wrote, “In creating burdensome barriers to participate fully as a member of the university community this policy promotes a complacent mode of civil engagement and punishes students who seek to freely assemble to make their demands heard.”

In addition to failing to obtain permission for the protest, the students who protested at convocation also violated a part of the policy that states that demonstrations can’t interfere with regular operations in campus facilities.

Zachary Greenberg, a senior program officer with the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, said it is fairly typical for universities to forbid protests from obstructing university events.

“The standard [at FIRE] is that they cannot severely and materially disrupt the event taking place,” Greenberg said. “Even minor disruptions are generally OK, as long as the event is allowed to go on. When it comes to making noise, chanting, yelling, pounding tables, noisemakers, when it prevents others from actually listening to the event and participating in the event, that would be something the university can punish.”

The Student Code of Conduct does not make explicit how punishments for violations are decided, but it does provide broad descriptions of when different penalties can be applied.

Ventura does not believe any other students have received such strict sanctions for staging protests without permission since the demonstration policy was instated—including during the nationwide Black Lives Matter protests that occurred in the summer of 2020.

One senior, Brooke McArdle, was charged in 2020 for violating the demonstration policy during a sit-in held to oppose the planned firing of hundreds of Marquette employees, but the penalties she received were not as harsh as those received by the convocation protesters. According to a post on McArdle’s Medium blog, the sole consequence she faced was to write a seven-page essay suggesting ways Marquette could improve its demonstration policy. If she didn’t complete it, administrators told her, she would be placed on probation.

Griffith, the Marquette spokesperson, said the two incidents were not comparable, because “the demonstration referenced from 2020 did not impede a university-sponsored activity, while the demonstration at New Student Convocation did.”

Still, the students and their supporters have cited such discrepancies in questioning how the university decided what sanctions to impose.

According to Griffith, “Marquette stands firmly behind its student conduct process, which has adjudicated hundreds of cases each year for decades and is reviewed on a regular basis. It is important to note that there are a wide range of outcomes for students who go through the student conduct process, and an outcome for one student does not necessarily equate to the same outcome for another.”

She did not clarify why some students received suspensions in abeyance and others did not, nor why the $300 fine was dropped but other penalties were upheld, citing the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, a federal law that governs what student information schools can release and to whom.

Community Support

On Sept. 28, the day the protesters submitted their appeals, faculty and students demonstrated together to encourage the administration to drop the charges. The executive committee of the campus’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors also wrote a statement supporting the students, arguing, “The administration’s response to the protest is not only procedurally questionable, but it disregards Marquette’s core values and contradicts its public statements about its commitment to students of color on campus. Punishing student leaders and repeatedly refusing to listen to faculty sends a chilling message that upper leadership will continue to resist open dialogue about the most important issues facing our campus community.”

Madelyn Davenport, a junior, started an Instagram account in support of the protesters that now has almost 250 followers; she also launched a petition, which has accrued more than 1,600 signatures, demanding that university officials repeal all the penalties.

“Students attend Marquette University in order to have a [J]esuit education, but Marquette is not upholding [J]esuit values by punishing these students. As Father Pedro Arrupe said, ‘Ultimately, we must understand the need to be agents of change,’” Davenport wrote on the Change.org petition, citing a former leader of the Jesuits.

Though the appeals did not succeed, Davenport says there is still widespread support for the student protesters.

“I think the people that have been caring are continuing to care. I don’t think there’s been a loss in stamina,” she said.

Still, the concerns the students raised during their protest at convocation appear unaddressed. Four positions in the Office of Engagement and Inclusion, including director, remain unfilled, according to Marquette’s employment site; the position of director of Black student initiatives, which falls under the Office of the Provost, has likewise been open since June.

For Stephanie Rivera Berruz, a philosophy professor and the co-director of the Center for Race, Ethnic and Indigenous Studies, it’s no mystery why the university struggles to retain employees, especially in support positions; they are paid poorly to juggle the needs of many different groups of students, while being given little support from the administration.

“My experience with folks who worked in [the Office of Engagement and Inclusion] is that it’s extremely exploitative, overworked, underpaid conditions and it’s the outcome of a model that thinks the way that you navigate diversity is by putting all nonwhite student initiatives in one office,” she said. “[They are] literally all housed in one location, which means that the staff for that office is playing not just double duty—it’s like quadruple duty.”

Several other people with knowledge of OEI agreed that its employees are underpaid and overworked.

Griffith said Marquette is currently recruiting for the empty positions, including for the next director of the OEI, a position that is being renamed the director of inclusion and belonging.

“While the university would certainly like to have all open positions filled immediately, Marquette is facing the same staffing and recruiting challenges as organizations nationwide, and it takes time to find the right people to do this important work,” she said.

She noted that the university is also hiring a new staff member for the Urban Scholars Program, which serves primarily first-generation college students from low-income backgrounds.

Rivera Berruz believes it’s disingenuous for the administration to attribute its staffing woes to nationwide recruiting challenges.

“What that occludes is that there is, really, behind the scenes, a really large institutional negligence to attend to the types of resources that a diverse student body requires,” she said.

According to Davenport, one good thing has come from the debate over the protesters’ sanctions: it has focused attention on the issues they were protesting in the first place.

“I know that there are a lot of freshmen and some sophomore students who told me they were not originally aware of these issues and that it disheartens them,” she said. “I think a lot of people weren’t aware of these issues, especially because Marquette is a predominantly white and predominantly affluent student body base. I think this is a good wake-up call for a lot of people in order to be informed and understand what’s going on.”