You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Tuition increases mostly remained low despite runaway inflation in part of 2022.

AndreyPopov/iStock/Getty Images Plus

College tuition and fees increased at a historically low rate for a third straight year, according to a new report out today from the College Board, which finds that tuition actually decreased during the 2022–23 academic year when adjusted for the runaway inflation that hit the U.S. economy.

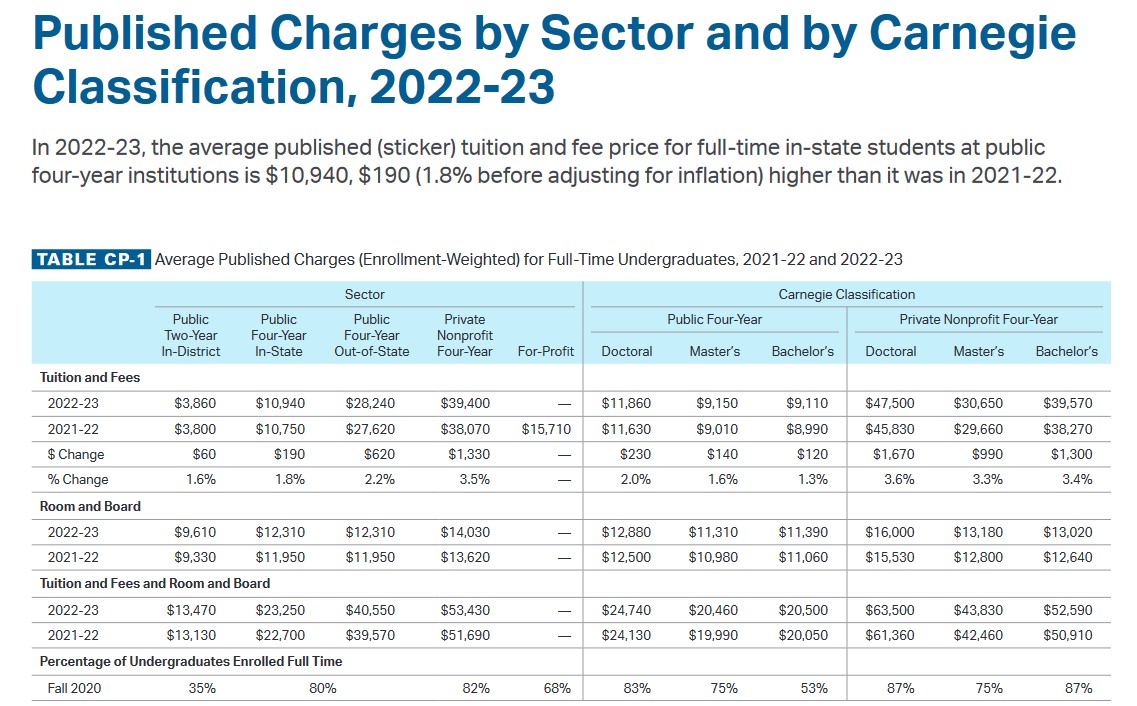

Average annual tuition and fees—before adjusting for inflation—ticked up by 1.8 percent for in-state students at public four-year institutions, 1.6 percent for students at public two-year colleges and 3.5 percent for those at private nonprofit four-year colleges, according to the report, “Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid.” Taking inflation into account, the average tuition and fees “declined in all three sectors,” the report said—though some individual institutions did significantly increase tuition due to inflation. (This paragraph has been updated to include the report's proper title and link.)

The data also show that borrowing continued to decrease as it has every year since the 2011-12 academic year, when it peaked due to the influx of students during the Great Recession.

Report Findings

Jennifer Ma, a senior policy research scientist at the College Board, said the findings from the annual report are broken down into four main themes. First, average college costs are climbing only slightly. Ma said she was “expecting higher increases” and was happy to see them stay low.

She pointed out that the average tuition and fees didn’t increase at all at two-year institutions in eight states and held steady for public four-year institutions in another nine states.

Second, Ma noted that “annual borrowing declined for the 11th year in a row.”

The third trend is the continuing decline in net prices in recent years.

“That’s really good news for students and families in terms of paying for college,” Ma told Inside Higher Ed.

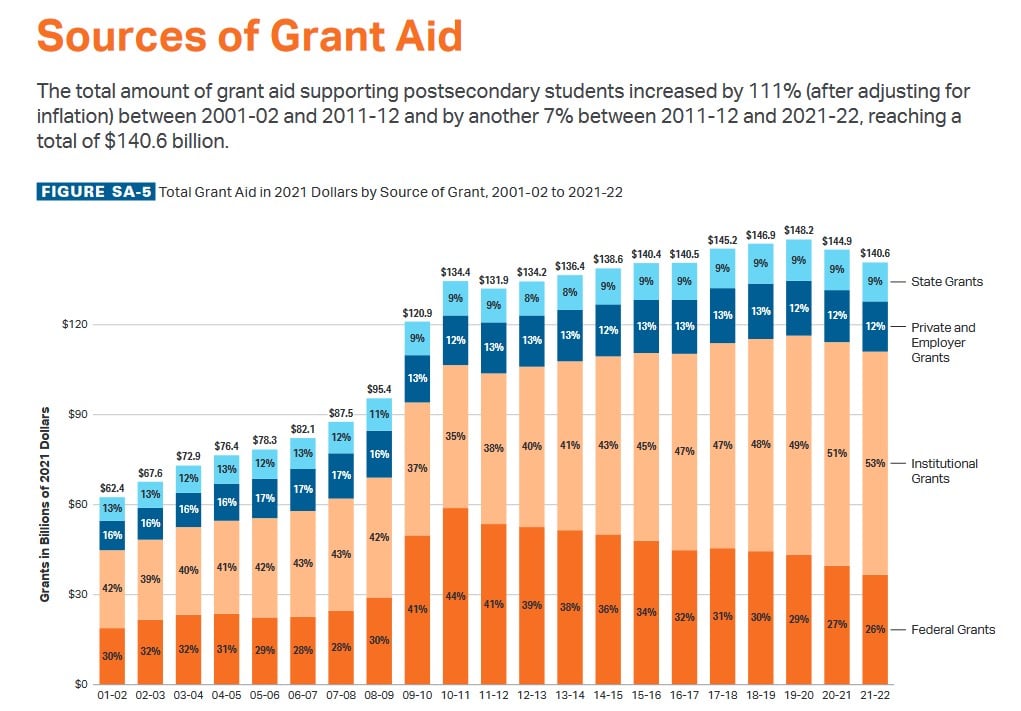

And lastly, she pointed out that “total grant aid dipped for the second year in a row after adjusting for inflation.” The decline “is primarily related to the decline in enrollment” across higher ed, Ma said.

Florida had the lowest sticker price for in-state students attending four-year public institutions, coming in at $6,370 for the 2022–23 school year, according to the College Board report. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Vermont’s in-state tuition hit $17,650. Nationally, the average cost was $10,940.

The average net price—the amount paid after federal and institutional grant aid is applied—for students at public four-year institutions was estimated at $2,250, compared to $14,630 at private nonprofit four-year institutions.

Among private nonprofit four-year institutions, the average net price was $39,400.

For public two-year colleges, California was the most affordable, with an average net price of $1,430 for those paying local rates. By contrast, Vermont’s two-year colleges cost $8,660, which is more than $1,300 higher than the next costliest state. The national average for two-year institutions was $3,860.

Looking back at financial aid trends for the 2021–22 academic year, the report found that full-time undergraduates received an average of $15,330 in grants, federal loans and other aid combined. Full-time graduate students received an average of $27,300 in financial aid.

All together, undergraduate and graduate students received $234.6 billion in financial aid in the 2021–22 academic year from grants, federal loans, work-study programs and tax credits and deductions. Students and families borrowed a total of $94.7 billion in federal and nonfederal loans.

Expert Reactions

Outside experts noted numerous factors that explain why tuition increases continue to tick up at historically low rates—even though inflation hit 8.3 percent earlier this year.

“Tuition increases are staying low for several reasons. The first is at many public universities, they aren’t being allowed increased tuition. The state Legislature or the state higher education agency just tells them no,” said Robert Kelchen, professor and head of the department of educational leadership and policy studies at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. “Another factor is most colleges don’t have very strong market power to increase tuition right now. Enrollment across higher education is down, and they’re concerned that if they increase tuition, they’ll lose students to other colleges. And then the third reason is that colleges are trying to keep tuition increases as low as possible because they know that a lot of students are having a hard time affording college. If they increase tuition too much, students may not be able to continue.”

Beth Akers, senior fellow at the center-right think tank the American Enterprise Institute and an economist by training, offered a similar perspective, adding that student skepticism of higher education and climbing costs for American households may have prompted colleges to hold tuition rates down.

“The surprising side is that we’re seeing prices rise in every other major sector of the economy with historic levels of inflation. So I think it would not have been surprising to see prices increasing in higher education at a similar rate, or at least faster than they had been increasing in the past, because institutions, like everyone else, are having to pay the higher costs of existence, which means energy prices and wages paid to workers who make the campuses run,” Akers said. “On the other hand, we’re seeing declines in enrollment. It seems that students over the past few years may have started to grow more skeptical of what it is that traditional higher education is selling them, and maybe institutions are feeling the pressure to charge them prices that try to send the message that they’re offering value with their enrollment experience.”

But with inflation continuing to climb, both Kelchen and Akers noted that it will be hard for colleges to keep prices down, especially given the rising costs of running a campus.

Kelchen pointed out that tuition increases in the public sector hover around 2 percent, but inflation has been as high as 8.3 percent this year, creating an unsustainable financial gap. While “state funding has helped with that gap” in some states, he said, that isn’t true across the board. Many colleges are trying to cut costs in various ways, such as by terminating employees, keeping vacant positions open for longer periods of time and reducing dining hall hours, for example.

Going forward, he suspects that if institutions can’t raise tuition to cover their costs, they may resort to larger classes, fewer academic advisers and reduced services over all.

Akers said that while colleges have been able to make cuts in order to offset increased costs, that solution is temporary. Ultimately, she believes colleges and universities will have to find the answer in innovative solutions. And if they can’t innovate their way to success, consumers will pay the price.

“What we’re seeing here is that institutions are able to absorb the rising costs of doing business by reducing expenditures on other things,” Akers said. “It’s not clear that they’ll be able to do that forever. And if we have continued inflation that drives up their cost of operating even further, it may be that ultimately gets passed on to students in the form of quickly rising prices.”