You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The University of Notre Dame sponsored a cybersecurity festival in October.

University of Notre Dame

When Whitworth University was hit by a cyberattack earlier this year, it faced a public relations nightmare, significant financial strain and a data breach that may have affected thousands of former and current students and employees. The incident was one of an increasing number of cyberattacks against colleges since 2020. Such attacks have more often succeeded against higher ed than other sectors, including business, health care and financial services.

Though college information technology offices have long worked behind the scenes to bolster institutional defenses, their countermeasure efforts, such as installing network threat detection and risk-mitigation systems, are often invisible. Meanwhile, students and faculty and staff members—end users—who remain unaware of security threats pose significant risks.

Mandatory cybersecurity-awareness training helps but is often top-down and requires email nudges from managers, according to Chas Grundy, IT strategy and transformation director at the University of Notre Dame. As a result, community members are often slow to engage.

This year, Notre Dame decided to do something different: a cybersecurity festival intended “to reach people’s hearts and minds in a way that would stick and draw them into it as a counterpart to mandatory training,” Grundy said.

Notre Dame is one of several institutions experimenting with unconventional cybersecurity awareness training in the form of festivals, art installations and role-playing games. Here’s a sample of serious cybersecurity training in fun formats, including some lessons learned and wins along the way.

Cybersecurity Festivals

Cyberthreats are the “No. 1 risk” to Notre Dame, the institution’s Board of Trustees told Grundy.

“End users are risk vectors for all of this—gift card scams, job scams, phishing, research compromise, compliance,” Grundy said in a session on the topic at the 2022 Educause Annual Conference. “It’s really important that end users get cybersecurity education.”

Grundy and his team understand community members’ blind spots, which include poor-quality passwords, the inability to recognize phishing scams and inaction in securing home networks and devices. To bolster knowledge, the team envisioned a highly visible and inviting cybersecurity carnival that would accommodate a variety of engaging activities. They paired their idea with 1,600 balloons, 9,750 pieces of candy, 1,500 bags of popcorn, 1,300 wads of cotton candy, 50 volunteers, 19 art parodies, five skits and eight carnival games on cybersecurity themes.

The cybersecurity strongman game, for example, asked carnival attendees to choose the strongest password from a selection of options. A “go phish” activity asked attendees to spot indicators of a phishing email. A “slam the spam” trivia event quizzed participants on security trivia. A lock-picking workshop allowed participants to consider locks from a bad actor’s point of view and discover internal motivation to protect themselves better.

The cybersecurity strongman game, for example, asked carnival attendees to choose the strongest password from a selection of options. A “go phish” activity asked attendees to spot indicators of a phishing email. A “slam the spam” trivia event quizzed participants on security trivia. A lock-picking workshop allowed participants to consider locks from a bad actor’s point of view and discover internal motivation to protect themselves better.

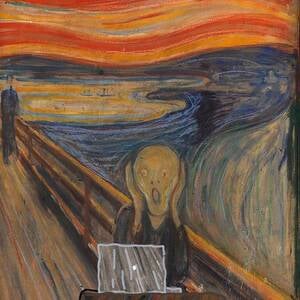

Art was prominent at the event that was held last month. In an exhibition titled, “Museum of Mishaps,” famous artworks were altered to depict cybersecurity gaffes. Johannes Vermeer’s Girl With a Pearl Earring was parodied as Girl With an Open Webcam. Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory morphed into The Protection of Memory. Caravaggio’s Boy Bitten by a Lizard became Boy Bitten by a Phish. Students also performed live sketch comedy in an event called Security Night Live.

Notre Dame’s cybersecurity carnival attracted 1,000 community members, skewed slightly toward faculty and staff (43 percent students and 57 percent staff and faculty). Nearly all (96 percent) reported that they would recommend the event to a friend or colleague.

The core information technology team did not have the capacity to plan, deliver and fund the event on its own, said Elizabeth Lankford, an IT service management professional at Notre Dame. Out of necessity, the event was a communitywide effort.

“Tap people, give them room to flourish, tell them ‘Here’s a way for you to be a leader,’” Lankford said. The team also recruited student workers, who subsequently recruited their friends to attend the event.

The team sought funding from vendors. Chris Daugherty, a field representative for Google, considered the company’s sponsorship a win, as the top two most-scanned QR codes of the day were, “How do I get a job at Google?” and “How do I secure myself in a Google environment?”

The team sought funding from vendors. Chris Daugherty, a field representative for Google, considered the company’s sponsorship a win, as the top two most-scanned QR codes of the day were, “How do I get a job at Google?” and “How do I secure myself in a Google environment?”

The team missed some opportunities, Grundy said. The campus art museum, for example, loved and wanted to contribute to the Museum of Mishaps when they found out about it—a day after the event.

Also, to market the event, students dressed in costumes to hand out fliers. Those dressed as cops who handed out “tickets” advertising the event were popular. But others dressed as “cybersecurity clowns,” wearing T-shirts with slogans such as “my password is 1234,” were shunned.

“Most humans encountered the clowns, and it was like the magnetic opposition,” Grundy said. “Being in costume on campus as clowns was definitely a lesson learned—not effective.”

Stanford University also recently hosted a cybersecurity festival—one focused on safe cloud computing practices. The event, whose tagline was “cloudy with a chance of awesome,” featured high-profile speakers, including former secretary of state Condoleezza Rice, as well as engaging activities such as lock-picking and hacking activities.

“When you think cybersecurity, you may think of a hacker in a hoodie in a dark, mysterious room,” said Amy Steagall, chief information security officer, who believes that students and staff are an institution’s first line of defense. “I’m trying to make the information security office not dark and mysterious to our community. The festival gave us a platform for people to come up and talk about cybersecurity with us.”

IT professionals may never know whether their cyberawareness training averts a disaster that otherwise might have happened. Still, many see signs of enhanced digital literacy in their communities.

“When I start hearing things like, ‘Hey, I don’t need to get these phishing campaign emails anymore because I recognize them every time,’ that’s when I know that what we’re doing is working,” Steagall said.

Cybersecurity Art Installation

Cybersecurity Art Installation

End users who experience a deadly denial-of-service attack often do so in the relative comfort of their home or college while staring at a quiet monitor that loads an error page. That experience does not hint at the flood of traffic that, in the moment of an attack, crashes the victim computer.

To spur people to consider the “noise” of a denial-of-service attack, Tanner Upthegrove, a media engineer at Virginia Tech, created Tesseract, an immersive audio experience.

“We’re all familiar with visualization of data, but we’re not taking advantage of the incredible human ear, which has less fatigue than, say, if you’re looking at a screen for many hours,” Upthegrove said. “The human ear can hear sounds coming from all directions and parse those streams extremely well.”

When someone steps inside Tesseract—a cube outfitted with 32 loudspeakers—they initially experience an audio simulation of cybersecurity data in a normal state of operation, followed by an audio simulation of a deadly denial-of-service attack.

“Say you have a constant tone—ooooooo—and then the tone changes—whoa whoa whoa. It’s a pretty clear change to the human ear,” Upthegrove said, even when a collection of such changes emanates from many speakers. “For someone who’s never experienced an immersive auditory display like this tesseract system with 32 or 64 loudspeakers around them, just hearing intentional sounds happen overhead, behind, even underneath is novel, even though that’s how we always hear everything.”

Most everyone begins the experience in a state of intentional listening, Upthegrove reports. At first, the ambient sounds are soft and low. When participants walk around inside the cube, the sounds change as they move. In time, the sounds build to a cacophonous moment intended to depict the moment a cyberattack overwhelms a victim computer and its aftermath.

“It creates some empathy,” Upthegrove said of the sonification of data. “Using spatial audio to convey abstract things really resonates—no pun intended—with a lot of people.”

Cybersecurity Role-Playing Games

Louisiana Tech University put an interdisciplinary, murder-mystery spin on its cybersecurity-awareness efforts. Students, faculty members and staff enter simulated environments to participate in the Analysis and Investigations Through Cyber-Scenarios’ role-playing games. There, they act on teams as government officials facing real-world cyberattacks.

Participants are encouraged to think critically as they work to resolve the scenario that was designed by faculty from computer science, history, engineering, literature, math and political science. In the process, they raise their cybersecurity awareness from social, political and ethical viewpoints.

The university has also extended the program to high school students in the community.

“It’s self-serving for the university, because we’re able to recruit a lot of really strong students not only to the college of engineering and science but also to the university,” said Heath Tims, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Louisiana Tech. As a bonus, when past program participants later enroll at the college, they arrive armed with enhanced cybersecurity awareness.