You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The popular app TikTok is being restricted from being used on state-owned devices and Wi-Fi networks at many public universities across the nation.

Matt Cardy/Getty Images

Public university administrators who comply with state policy bans on accessing TikTok via state-owned Wi-Fi networks and devices might understandably expect pushback—or at least frustration—from their student bodies.

Instead, many students seem to be indifferent. With a single click on a smartphone, most students can easily turn off campus Wi-Fi and switch to their personal cellular data to continue watching TikTok’s endless stream of content.

“It’s just going to become my mom’s problem,” said Jack Marshall, a student at the University of Montana, referring to the bump in cellphone bills that will likely result from watching TikToks using data—at least for those without unlimited data plans.

“We’re not going to stop using TikTok,” he said.

Others agree that prohibiting TikTok will not curtail its use. While reactions have varied—in one Reddit thread, a user celebrated the ban at the University of Texas at Austin not because of cybersecurity risks but because “TikTok is turning people into zombies”—TikTok fans and haters alike recognize that the ease of getting around the bans renders them virtually meaningless.

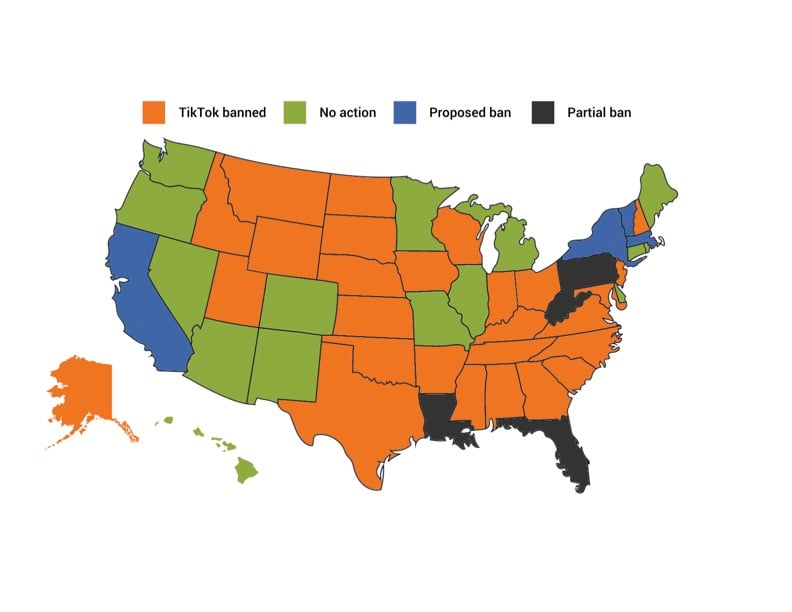

Public universities began blocking TikTok from use on state-owned devices and networks in late December, generally following orders by governors prohibiting state government employees from using the app on their work devices. Since then, a whopping 31 states have at least partially banned TikTok, according to CNN. These bans range from measures that only restrict certain government offices from using TikTok on state-owned devices to ones that prevent any employee from using TikTok on their work devices. Some also outlaw other apps and social media platforms that are seen as threats to cybersecurity. The impact on universities has likewise varied by state, with some governors encouraging their state’s public universities to restrict on-campus access to the app, while others don’t mention it at all.

Universities in Montana and Texas are the latest to implement bans on their campuses. In Texas, the University of Texas at Austin, the University of Texas at Dallas and the Texas A&M University system all announced bans on Tuesday, after Governor Greg Abbott said earlier this month that the app would be banned from government-issued devices.

Montana’s governor, Greg Gianforte, issued a similar directive in December and asked the Montana University System’s Board of Regents to consider following suit. The system subsequently announced that such a policy would go into effect on Friday, Jan. 20.

Not every state government ban has impacted that state’s public universities, however; Maryland’s universities, for example, have not restricted the app despite an emergency directive in December banning several apps thought to be affiliated with the Chinese and Russian governments—including TikTok—from use by state employees. In Oklahoma, Governor Kevin Stitt prohibited state-owned devices and networks from accessing the app. While several universities followed the directive, at least one, the University of Oklahoma, is considering rolling back the ban after determining Stitt’s executive order did not specifically include universities.

Not every state government ban has impacted that state’s public universities, however; Maryland’s universities, for example, have not restricted the app despite an emergency directive in December banning several apps thought to be affiliated with the Chinese and Russian governments—including TikTok—from use by state employees. In Oklahoma, Governor Kevin Stitt prohibited state-owned devices and networks from accessing the app. While several universities followed the directive, at least one, the University of Oklahoma, is considering rolling back the ban after determining Stitt’s executive order did not specifically include universities.

“We are now undertaking a review of the security concerns that TikTok may pose to our network systems while giving consideration to how a ban would impact our university community. We are continuing to work on our review, using our governance processes, and we expect to finalize an updated response in the next few weeks,” a university spokesperson, Jacob Guthrie, told Inside Higher Ed in an email.

Cybersecurity Concerns

Increased scrutiny of the app emerged after FBI director Chris Wray voiced national security concerns about it in December. TikTok, which is owned by the Chinese company ByteDance, collects a wealth of user data—including, according to lawsuits against the app, information about users’ faces, voices and fingerprints—which leaders worry will be used by the Chinese government to spy on or blackmail users in the U.S. (TikTok has said that all its data are stored in the U.S. and Singapore.)

“The ability of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to spy on Americans using TikTok is well documented,” Gianforte wrote in his letter to Montana’s regents. “Using or even downloading TikTok poses a massive security threat. Data of TikTok users have been repeatedly accessed by the CCP, and TikTok will not commit to stopping it. In fact, one privacy researcher indicates TikTok can monitor a user’s keystrokes, potentially exposing user information like credit card numbers and passwords.”

Leaders are also concerned about the app’s ability to push propaganda and censor videos that are critical of China.

But if the goal is to discourage students from using the app, banning it from campus devices and Wi-Fi is unlikely to have any effect. Not only are students able to access TikTok in other ways; they also don’t see using it—or any app that collects their information—as truly risky.

“A lot of social media takes a lot of our data,” said Marshall, who is also the sports editor at UMT’s student newspaper and has run a parody TikTok account of the university’s football team, the Grizzlies. “As far as TikTok’s concerned, I feel like it’s a lesser evil, especially in Montana at some public university.”

To some extent, the experts agree. Thomas Skill, CIO of the University of Dayton, a private Catholic university in Ohio, and the acting director of the university’s Center for Cybersecurity and Data Intelligence, said that nearly every free social media app sells user data. That can be a problem if, for example, a phishing scammer acquires your personal information and crafts an elaborate scheme to trick you out of your credit card or Social Security number.

“We have a real, severe problem with these free social apps capturing all kinds of information,” Skill said. But he doesn’t see TikTok’s data collection as more egregious than other apps’.

In his view, changing students’ lackadaisical attitude toward sharing their data would make a bigger impact than trying to prohibit them from using the app. Many students don’t feel the need to protect their data because they have little they could lose in terms of assets, Skill said.

He noted that it can be helpful to teach students more about what information is being collected and demonstrating how it can be used in phishing attacks. One University of Dayton professor, he said, runs such a scam on his own students, promising extra credit in exchange for students’ data, in order to teach them to be more wary of requests for information.

“We have a bit of a challenge in helping our younger students in understanding the risks around what they’re willing to give up,” he said.

Beyond the personal risks of using an app that collects data, Skill doesn’t believe there is a real reason to ban the app. He said there’s no evidence that TikTok causes any institutional risk to universities when someone accesses the app through the campus Wi-Fi.

Stuart Madnick, a professor of information technology at the MIT Sloan School of Management and a longtime cybersecurity researcher, concurred.

“If you want to worry, there are bigger things to worry about,” he said. “There’s risk everywhere. Getting out of bed is a risk. I know people who have fallen in the shower.”

Both Madnick and Skill believe the bans are primarily political in nature, focused more on influencing public opinion of the universities than on mitigating any real risk. The bans can help universities appear to be making efforts to protect student data, which is significant as cyberattacks against institutions of higher education become more prevalent.

“Anybody who doesn’t view this as being primarily a political and financial matter is either kidding themselves or extremely naïve," Madnick said.

Skill called the measures “IT theater”—aimed at making people on campus feel safe without actually protecting their data.

Uncharted Territory

Although most campus TikTok bans are essentially the same, some universities are trying to figure out the best ways to implement them while minimizing the negative effects on students and faculty. Many student organizations use TikTok accounts to promote their clubs’ activities and events, for example, and there is uncertainty about how the bans will impact those accounts, if at all.

The Montana University System is currently considering additions to its policy that would address this issue. According to Helen Thigpen, deputy commissioner for government relations and public affairs for the system, Montana universities are “considering providing additional direction for existing accounts. We recognize that MUS campuses and student groups may have content they want to retain, and we are working through that process.”

Many of the institutions that have imposed bans previously ran numerous TikTok accounts that now seem to be inactive. Texas A&M’s football program, for example, has an account with about 124,600 followers. The account last posted in late November (though it was still visible as of Thursday evening); Abbott ordered TikTok be banned from state government devices the following week.

The Texas A&M system did not reply to an inquiry about the fate of the account.

The MUS, along with several other campuses, is also planning to make exceptions to the ban; faculty, staff and students who need to access TikTok for educational or research purposes may submit a request to their campuses’ CIOs.

Similarly, UT Austin will take requests for exemptions through its Information Security Office.

“Legitimate uses of TikTok to support university functions (e.g., law enforcement, any investigatory matters, academic research, etc.) will be considered," said Jeff Neyland, the university’s adviser to the president for technology strategy, in Tuesday’s announcement of the new policy.

Beyond confusion about how these bans will actually play out in practice, there is also concern that they could limit academic freedom or even violate students’ and professors’ First Amendment rights. The app has a number of legitimate uses in the classroom; a professor may assign students to distill a difficult concept into a video on the app, which has become a popular platform for spreading quick snippets of information.

Theresa Kadish is a graduate student at Binghamton University in New York who is involved in the university’s Digital Storytelling Initiative, which works to incorporate digital storytelling into pedagogy at the university. She has taught courses on TikTok, which she said is a particularly useful educational tool because it has a simple-to-use interface and students are very familiar with it.

“As an educator, whether you know a lot about video editing or literally nothing, you can tell your students, ‘Hey, go film a video about your thoughts about that article you just read,’ and they can just do it,” said Kadish, who is a TikTok creator herself, adding that a professor who is using TikTok in the classroom should be sure to warn students about privacy concerns. “But the actual technical side of producing a piece of content is streamlined in a way that simply wasn’t there before 2019.”

David Greene, civil liberties director and senior staff attorney at Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital rights nonprofit, said that whether these bans violate the First Amendment will likely differ from university to university. It depends on what the university hoped to accomplish with the ban, he said, and whether it could have been achieved in a less restrictive way. Like Skill, he believes that in some cases, universities could try educating their students about the risks of using TikTok and other platforms that collect and share user data before implementing a ban.

Additionally, the many opportunities students have to go around the bans may be a point against them.

“You can’t just restrict speech in a way that is completely ineffectual or even largely ineffectual,” he said.

Some also fear that TikTok bans could set a worrisome precedent for universities preventing other sites from being accessed on campus.

“We’re very, very cautious about voluntarily blocking legal content from the internet. As long as it remains legal, while we certainly hope people would make good decisions … the idea of blocking it seems counter to academic freedom and curiosity,” said Skill, the University of Dayton CIO. “Every interest group in the world wants us to block [something].”