You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

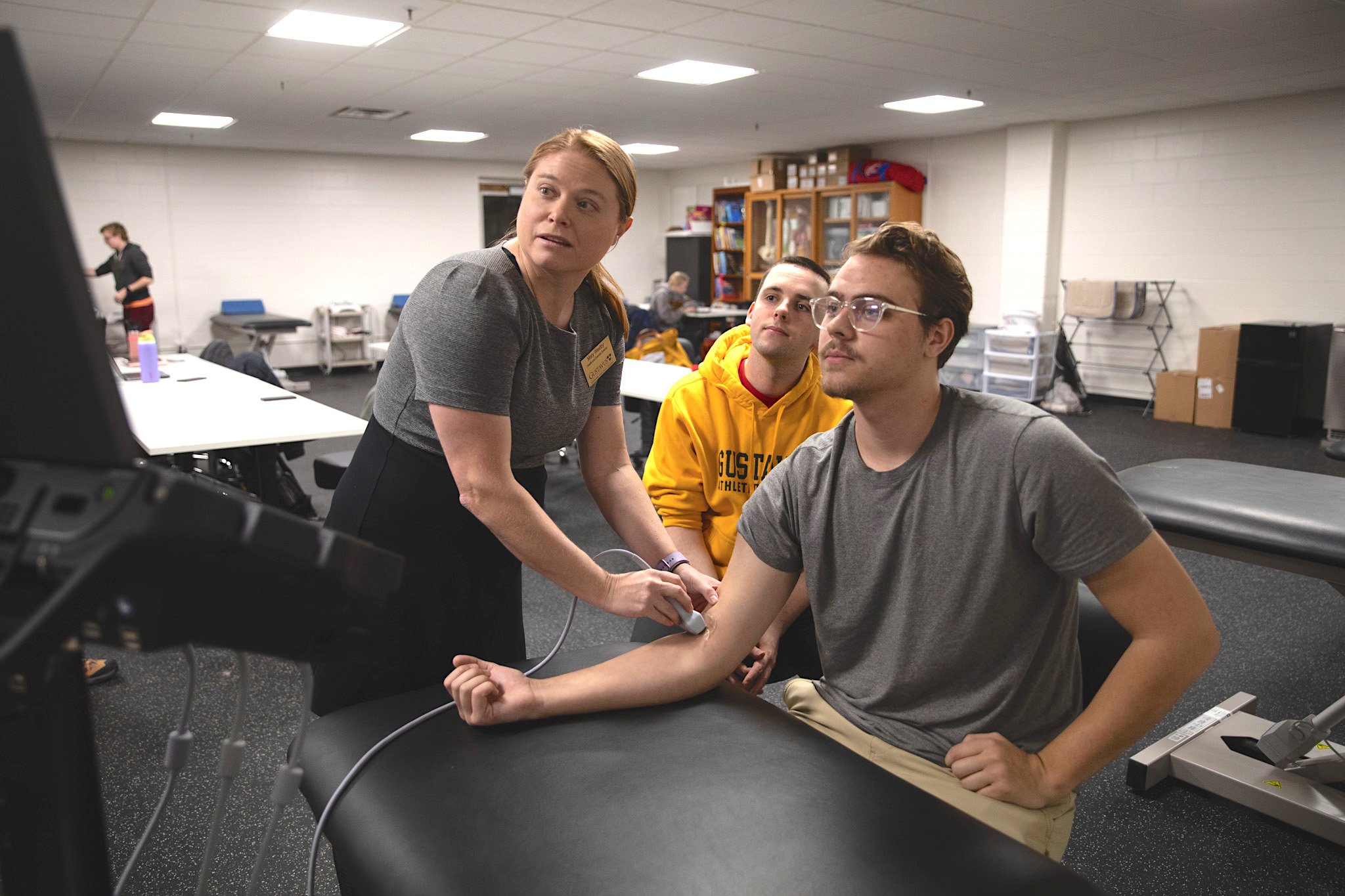

Gustavus Adolphus College is adding a master’s program in athletic training, the college’s first-ever graduate program.

Gustavus Adolphus College

Gustavus Adolphus College went 161 years without any graduate programs. But a combination of competitive pressures, demographic patterns and accreditation requirements in one of its most job skill–focused undergraduate fields has led the private liberal arts institution to create its first-ever master’s degree—and to consider adding others.

Like other small private institutions, Gustavus Adolphus, a Lutheran college in southern Minnesota, faces a shrinking pool of traditional-age students, even ahead of the projected decline in college-age students due to kick in later this decade.

While many of its peers have added master’s programs to their offerings, officials at Gustavus Adolphus never came close to doing so until eight years ago, when a national coalition of athletic training organizations announced a policy change requiring trainers to have master’s degrees to become certified. Gustavus Adolphus already had a bachelor’s degree program in athletic training, so the college’s administrators decided to start a master’s program.

“It seems natural that something like this would be our first step into a master’s program or a higher-level degree,” said Brenda Kelly, provost and dean of the college, citing the lengthy history of the undergraduate athletic training program, which began in 1976.

The plan also looked ahead; the college’s future partly hinges on managing a shift in student expectations, said Chris Rasmussen, a Gustavus alumnus and former trustee.

“The larger kind of challenge here is, how does a place like Gustavus continue to be relevant to a group of students coming up through high schools, and their families for whom they’re making a different kind of return-on-investment calculation?” said Rasmussen. “They want, I think, more of an assurance going into their college experience that this is going to lead toward remunerative employment.”

Rasmussen recalled how the college’s board, made up mostly of alumni, grappled with the idea of adding graduate students after the 2015 announcement by the athletic training coalition about the policy change requiring a master’s degree for a person to sit for a certifying exam.

This past fall was the last semester a bachelor’s degree program in athletic training program could admit new students, according to Dale West, executive director of the Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education.

“There are a small collection of decisions you would make as a governing board and as an institution’s leaders that really kind of change the direction of the institution, and one would be entering into graduate programs. It wasn’t something that was ever taken lightly,” Rasmussen said in an email, recalling a “lengthy” and “deliberative” decision-making process while he served on the board from 2014 to 2018.

Kelly, also an associate professor biology and chemistry, joined the college 21 years ago and became interim provost in 2016 and permanent provost in 2018. She said that while talk of creating graduate programs may have been “floated” before 2015, college administrators did not formally consider adding graduate programs until the athletic training policy change.

Kelly, also an associate professor biology and chemistry, joined the college 21 years ago and became interim provost in 2016 and permanent provost in 2018. She said that while talk of creating graduate programs may have been “floated” before 2015, college administrators did not formally consider adding graduate programs until the athletic training policy change.

“In the early-2010 years, we had some of our largest-enrolling classes ever in the history of the college,” she said. “At that time, I think there was not a particular need for the college to expand into other markets.”

But enrollment has since declined. It dipped to 2,042 full-time-equivalent students this academic year, down about 8.2 percent from the previous year and about 18.4 percent from 10 years earlier, according to data from a university spokesman and a bond statement issued in 2017 to help the college finance some campus projects.

“I think the college eventually, between 2015 and 2020, would have said, ‘Hey, we should start considering offering master’s programs,’” Kelly said.

She said initial discussions about adding a master’s program in athletic training began in the 2015–16 academic year, with the college’s board getting an early proposal for the program in spring of 2017.

Rasmussen recalled the board discussing the advantage of having an existing athletic training program.

“Really, the thinking on the board at the time was ‘We don’t want to give this up. This is an area of strength,’” he said.

Kelly said there were also discussions about whether graduate programs fit with the college’s mission.

“Our mission doesn’t include the word ‘undergraduate’ in it,” she said.

The college has “a history of preparing folks to serve in specific vocations,” Rasmussen said, referring to a nursing program that began in 1956 as well as teaching and other programs. “This was an extension of that mission and that strength.”

The Board of Trustees approved the new program in 2019, Kelly said.

Maddie Derbis, a senior majoring in athletic training and president of the Gustavus Athletic Training Association, a student group, said she welcomed the new master’s program.

“I think it’s great that Gustavus is allowing future students to step into that level of higher education,” she said, noting that she has seven classmates in the program who are also seniors. “It feels very validating.”

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projected a growth rate of 17 percent in athletic trainer positions from 2021 to 2031 and described the rate as “much faster than the average for all occupations.”

While some private colleges in the state have added graduate degree programs, others have not.

St. Olaf College, Macalester College and Carleton College, all members of the Minnesota Private College Council, don’t have graduate degree programs, said John Manning, the council’s director of marketing and communications.

Lauren Edmonds, senior director of the market insights service with consulting firm EAB, which is not working with Gustavus on the graduate program expansion, said more residential liberal arts colleges are exploring the idea of adding graduate programs, and some may feel pressure to do so in order to grow enrollment.

“Adding a new graduate program opens them up to a new audience they could be serving,” Edmonds said. Some colleges also see graduate programs as providing a “value option” for current students, keeping them on campus longer. But doing so might pose new questions for a college that mostly admits students directly from high school.

“How are we expecting people to live in the local community? Will we provide housing on campus?” Edmonds said, noting other considerations such as whether career services will have to be beefed up and more parking spaces added on campus. “It’s not a decision to make lightly. You want to consider, what are those added costs going to be?”

Kelly said Gustavus Adolphus administrators did a financial analysis of both the costs and revenue associated with adding a graduate program, which showed profitability after the start-up year.

Start-up costs are expected for such things as hiring additional faculty members and an initial outlay of about $100,000 for more equipment such as training tables and a larger ice-water bath, Kelly said.

“In that fiscal year, we have more total expenses than not,” she said of the program’s first year. “But by the following year, we’re already revenue positive.”

The numbers are projections, and the college’s administrators tried to look at the program’s first 10 years, Kelly said. The key will be enrollment, with eight students in each year of the graduate program, or 16 graduate students total, required to break even financially.

The program will have the capacity for about 20 slots in each class of graduate students, with the first cohort expected to enroll in summer 2024. It will be structured as a “3+2” program, meaning that students who come to Gustavus as freshmen can earn both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in five years. While some students will enter the program after attending other institutions, current students will be given first priority.

Kelly said administrators are considering starting graduate programs in other areas. Given the 2024 timeline for the new master’s program, “We’re kind of looking at that timeline and thinking about well, what’s next?” Kelly said.

She said faculty members have ideas about graduate programs in nursing, education and the psychological sciences, among other fields, but no decisions have yet been made.

She said faculty members have ideas about graduate programs in nursing, education and the psychological sciences, among other fields, but no decisions have yet been made.

“In our ideal world, we would actually bring in our students at the undergraduate level,” and they would stay and get graduate degrees, she said.

The decision to add the master’s program also dovetailed with a push for greater diversity among the students, Kelly said. A strategic plan launched in 2016 listed “Diversify and expand the Gustavus community” as its first goal.

Derbis, the senior, said she’s enjoyed her time at Gustavus and sees the possibility of enrolling new students of different backgrounds as a plus for the college, which located on about 350 acres in a mostly rural setting.

“Creating a more diverse environment, whether that’s age or what state they’re coming from, it will add an additional element of diversity, which is always a good thing,” she said.

Mary Westby, the athletic training program director, said turning the training program into a five-year program may be more alluring for some students who think, “I can commit to this now, because I can get my full undergraduate experience and then commit to this afterwards.”

There’s also optimism that its existence will help with undergraduate recruitment.

“If we capture more students at the undergrad level because we have this program, then financially it will look even more favorable than what we’ve included in our model,” Kelly said.