You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

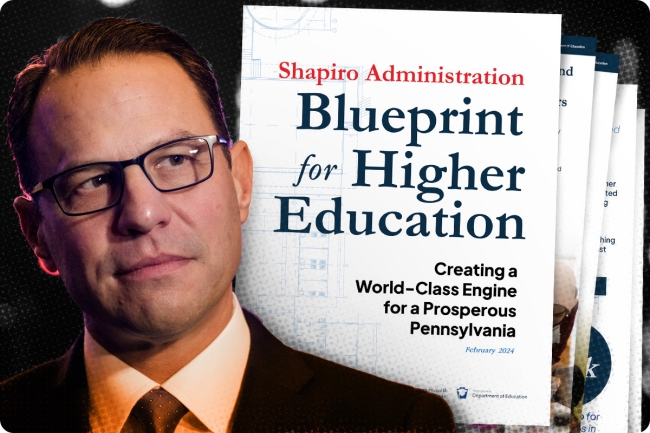

Pennsylvania governor Josh Shapiro has big changes in mind for state institutions.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Drew Angerer/Getty Images | Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

Battered by market headwinds, many institutions have turned to consolidation in recent years, seeking partnerships or mergers to help navigate enrollment challenges and financial issues.

Financial agencies including Fitch Ratings and Moody’s Investors Service have predicted more closures and mergers as market pressures intensify.

Against the backdrop of those challenges, the governors of Pennsylvania and Oklahoma, two states with bleak demographic outlooks, have floated consolidation plans as many institutions, particularly regional branch campuses, struggle to maintain their enrollments. The plans, floated by governors from different parties, show state governments eager to reshape institutions in a sector that has been squeezed in recent years by falling student head counts and rising operational costs, as well as by a crisis of public confidence in higher education.

The Pennsylvania Plan

Pennsylvania’s Democratic governor, Josh Shapiro, recently unveiled a plan called “A Blueprint for Higher Education,” which proposes sweeping changes, including the establishment of a unified system of state institutions and a new postsecondary funding formula.

Still in its nascent stages, the plan is short on specific details. But it aims to create a new governance structure to oversee the 10 universities in the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education and the 15 state community colleges to lower costs and produce more graduates.

“All existing colleges and universities will exist as equals in the new system; the goal is to coordinate, strengthen, and expand access—not shrink or consolidate. The governance structure must create a balance between system-level and local authority and responsibilities,” the plan reads in part.

Shapiro pointed to various concerns about higher education in the Keystone State to make his case, including the need to reverse “decades of disinvestment” and develop more collaborative efforts across “one of the most decentralized education sectors” in the nation. He also noted the need to fill workforce gaps that are expected to balloon due to a lack of credentialed talent for available jobs.

The plan would also radically lower tuition for students from families with an annual income of less than $70,000.

“Under my blueprint for higher education, Pennsylvanians making up to the median income [of $70,000] will pay no more than $1,000 in tuition and fees per semester at state-owned universities and community colleges,” Shapiro wrote on social media Thursday.

At this stage, Shapiro’s plan is more sketch than blueprint, prompting lingering questions from lawmakers—particularly state Republicans.

During a Senate appropriations committee hearing Wednesday, lawmakers grilled Pennsylvania Department of Education officials over the plan and Shapiro’s budget request: $975 million for higher education—an increase of about 15 percent over last year’s budget.

“This is helpful,” Republican state senator David Argall said in the meeting, holding up a copy of Shapiro’s plan. Then he added, “This is more foam than beer,” noting the need for further details, including on when a formal consolidation bill might come before the Senate’s education committee.

“This is a framework, not a done deal,” Pennsylvania education secretary Khalid Mumin told Argall, emphasizing that the plan is open to discussion and collaboration. He added that the blueprint was not ready to bring forward for legislators and offered no clear timeline for a bill proposal.

Dissatisfied with the answer, Argall suggested that Shapiro is essentially asking for a “blank check.” Other state lawmakers echoed similar concerns about the lack of specifics.

The blueprint noted that Shapiro is soliciting feedback “from the presidents of all 25 community colleges and PASSHE institutions; union representatives; legislators; and those involved in system, institutional-level or local governing and oversight,” with more details to come.

Oklahoma Explores Consolidation

In Oklahoma, Republican governor Kevin Stitt has also made a push for consolidation. Last month, in his State of the State speech, Stitt told lawmakers that he wants “regents to focus on consolidating colleges and universities” that are struggling.

“To be the best, we need to shift our focus to outcome-based higher education models and stop subsidizing institutions with low enrollment and low graduation rates,” Stitt said.

But so far, the governor’s office has not released a consolidation plan. The few details that have dribbled out via Stitt’s spokesperson have emphasized collaboration and complementary programs, especially for small institutions that are close geographically, though the idea could potentially apply to duplicate offerings at the University of Oklahoma and Oklahoma State University as well.

A spokesperson for Stitt did not respond to a request for comment from Inside Higher Ed.

State-Driven Consolidation

While closures and mergers have ticked up in recent years, especially among private institutions, consolidation is a complex task often fraught with thorny politics and pushback.

“I think change in higher education is incredibly hard. And obviously there are all kinds of constituencies on every individual campus that are going to be very resistant to change,” said Catharine Bond Hill, managing director of Ithaka S+R.

In small communities, where local colleges play an outsize role, the pushback may be fierce, given the potential loss of jobs and commercial revenue if a campus is shut down. That’s been the case with some recent state-driven consolidation efforts, such as in Wisconsin, where branch campuses have been shuttered or moved online, to the dismay of local officials and faculty members.

“Many of these institutions are anchor institutions in communities. Not only will you get resistance from legislatures, but from the communities themselves,” Hill said. “The local regional institution or the community college may be a major employer in the town and may be one of the few sources for young people to go and get more education. So certainly, there’s going to be some resistance there.”

To be sure, state-driven consolidation efforts aren’t always successful.

Mark DeFusco, a senior consultant with Higher Ed Consolidation Solutions, pointed to Alaska as an example of a failed attempt, noting a merger plan that was called off in 2020. At the time, the University of Alaska Board of Regents was exploring a potential merger between the University of Alaska Fairbanks and University of Alaska Southeast amid financial issues.

Regents walked back the plan due to widespread opposition by faculty and community members.

Other efforts have been more successful. Both DeFusco and Hill pointed to Georgia as one example. In 2011, the Georgia Board of Regents approved a consolidation plan that shrank the state system from 18 institutions to nine in staggered phases from 2013 to 2018.

While officials often cite cost savings as a key reason for merging state institutions, DeFusco said he doubts that cutting administrative overlap provides more than a short-term benefit; one-time efficiencies are unlikely to achieve long-term results, he said. Still, he hopes to see more states driving consolidation efforts.

Hill urged leaders not to be single-minded about cost savings but to think about broader outcomes as well, particularly how consolidation can affect access and opportunity for marginalized populations. From what she’s seen of the Pennsylvania plan so far, that seems to be part of the focus.

“I think Pennsylvania is trying very hard to keep students and student success at the center of what they’re doing within the constraints of the state. And if consolidations can do that, I think it can be part of the solution to the cost and educational attainment challenges that we’re facing,” Hill said.

Whatever happens in Pennsylvania and Oklahoma, DeFusco suggested it’s important to build consolidation efforts around state educational attainment goals with clear, definable metrics, including alignment with state degree-completion goals.

“In any merger and acquisition that I’ve done as an investment banker, there have been goals and metrics, because you have some view of a future in mind. In many cases, it just doesn’t happen for [state-driven efforts]. Someone has an inkling that it’s going to make our institutions better and stronger, but they often don’t define what that means and how they’ll measure it,” DeFusco said.