You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Jenny Kim/Inside Higher Ed

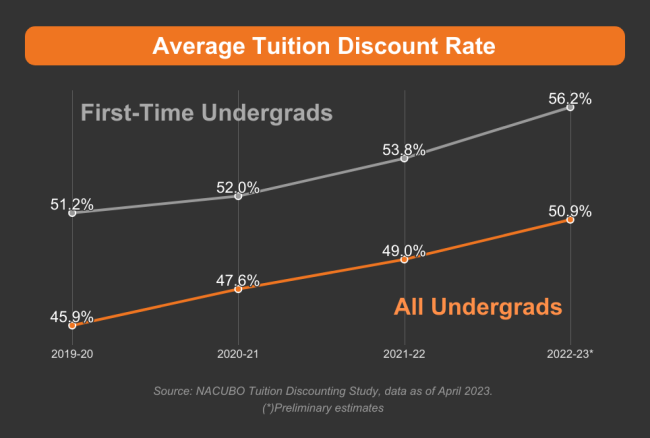

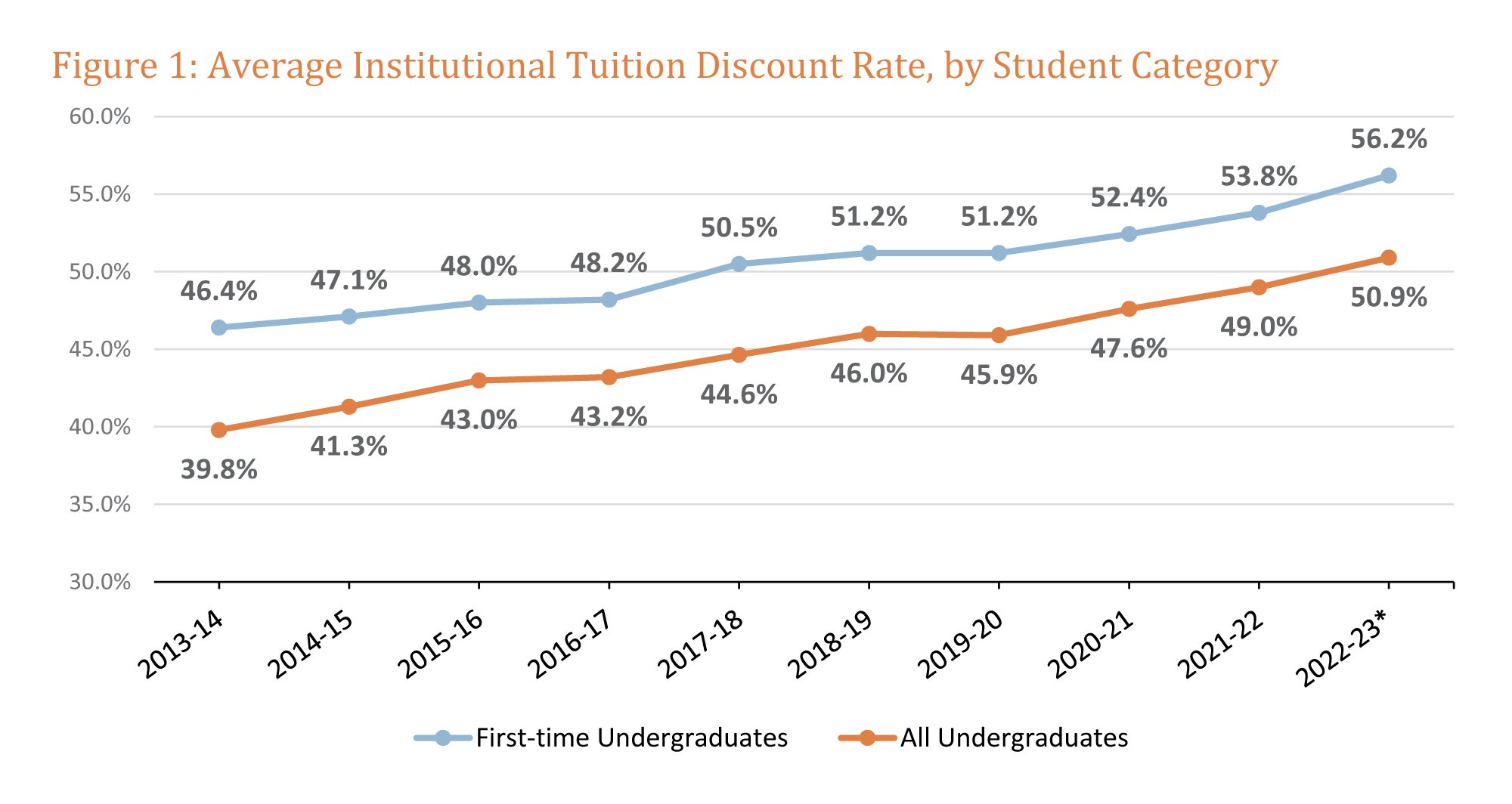

The average tuition discount at private nonprofit colleges once again hit a record high, according to a new National Association of College and University Business Officers study released this week.

A NACUBO press release noted that “the awards were, on average, the largest yet.”

The average institutional tuition discount rate was 56.2 percent for first-time, full-time freshmen for the 2022–23 academic year, and 50.9 percent for all undergraduates, according to early projections from NACUBO’s annual survey, which included 341 private, nonprofit institutions.

Both figures are record highs in the history of the survey, which dates back to 1994.

Last year’s study showed discount rates of 54.5 percent for first-time undergraduates, which itself was a record high, up from the past high of 53.9 percent in the study released in 2021.

By the Numbers

NACUBO defines the tuition discount rate in the study as “the total institutional grant aid awarded to undergraduates” by colleges and universities as “a percentage of the gross tuition and fee revenue the institution would collect if all students paid the full tuition and fee sticker price.”

The discount rate offers a snapshot of what students actually pay, with few families shelling out the full cost.

“That’s important because it demonstrates—from the perspective of families and students who attend or want to attend a private college—that institutions are devoting a lot of their own resources to make education more affordable relative to the tuition price,” said Ken Redd, senior director for research and policy analysis at NACUBO. “On the flip side, that also poses a challenge for many private colleges, since tuition and fee revenue is a large share of their overall funding, particularly for small to midsized private colleges, which don’t have large endowments.”

Among the key findings in the report:

- Net tuition and fee revenue fell by 5.4 percent for first-time undergraduate and by 5.9 percent among all undergraduates. The NACUBO study noted, however, that “institutions with minimally selective admissions criteria were slightly less affected by declines in net tuition revenue.”

- Of all undergraduates, 82.9 percent received grant aid, which “covered an estimated 62.1 percent of tuition and fees for first-time undergraduates and 57.6 percent for all undergraduates.”

- Most financial aid funded directly by institutions comes from undedicated revenue sources, such as available general funds, institutional reserves, endowment earnings and fundraising.

- Institutions with selective or highly selective admissions relied less on tuition discounting as an enrollment strategy than those with less selective admissions, offering a median discount rate of 46.8 percent for first-time undergraduates.

- The 341 private colleges surveyed reported an average enrollment decrease of 1 percent.

The Big Takeaways

Redd suggested that the study reveals two key points for higher education observers. First, it reflects the “extreme competition” for students, which “is going to continue for the foreseeable future,” he said; colleges are responding to that competition with increased aid. Second, the results illustrate the rising need for families, which colleges are meeting by increasing aid packages to enhance access.

For consumers, the rising discount rate means more money to help families make ends meet. Or, as the report itself puts it, colleges are forgoing tuition revenue to provide greater access to students.

“Despite modest declines in enrollment, the data show that the participating institutions delivered on their commitment to college access,” the NACUBO study stated. “Specifically, the results suggest that many private, nonprofit colleges and universities made significant investments to make higher education more affordable. Campus administrators continue to find efficiencies and new ways to offer high-quality postsecondary education without growing tuition revenue.”

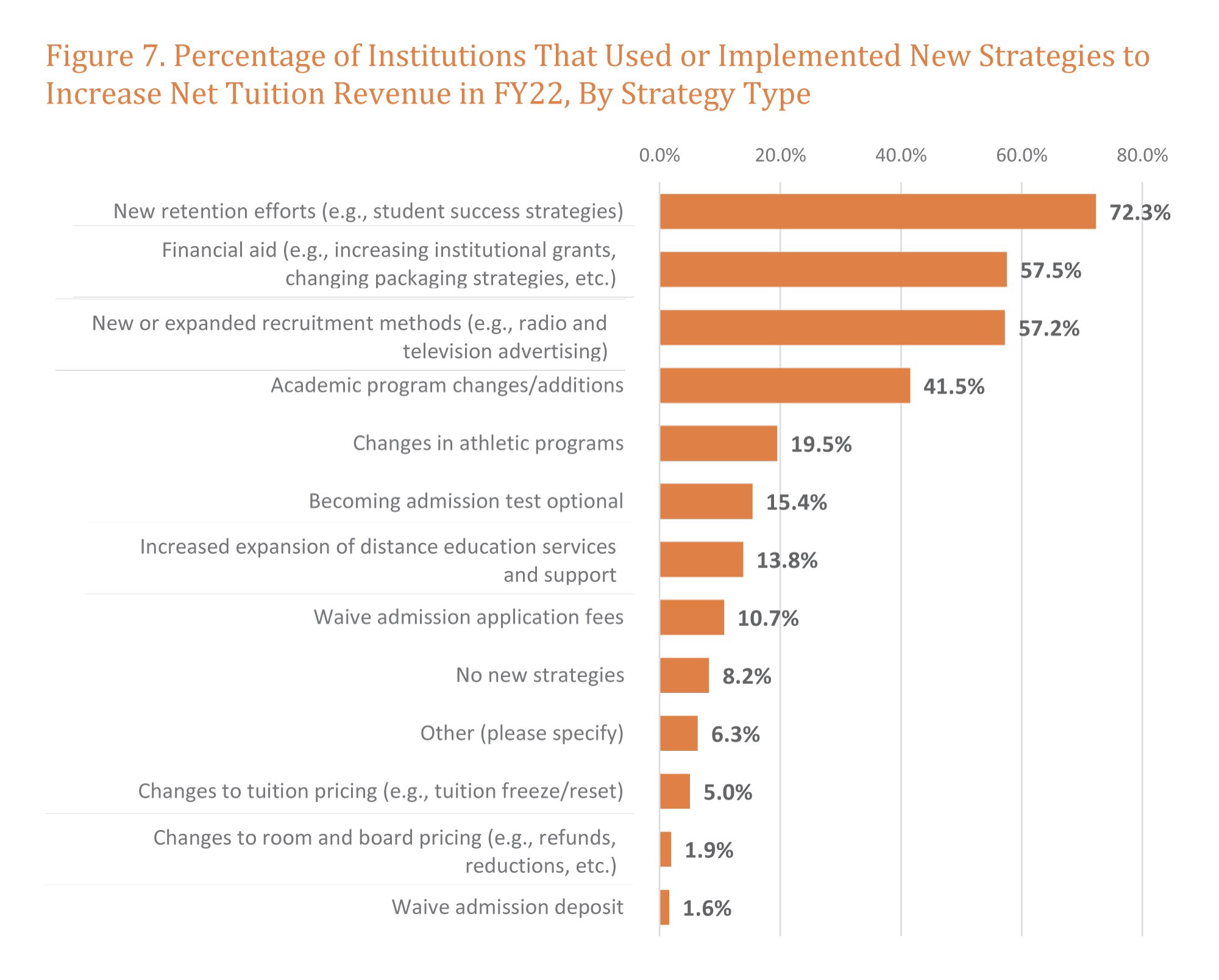

The NACUBO study also looked at the strategies colleges leveraged to increase net tuition revenue. It found that 72.3 percent introduced new retention efforts; 57.7 percent made financial aid changes, such as increasing institutional grants and other moves; 57.2 percent offered new or expanded recruitment methods; and 41.5 percent made academic program changes or additions. Institutions also reported various other strategies to increase tuition revenue.

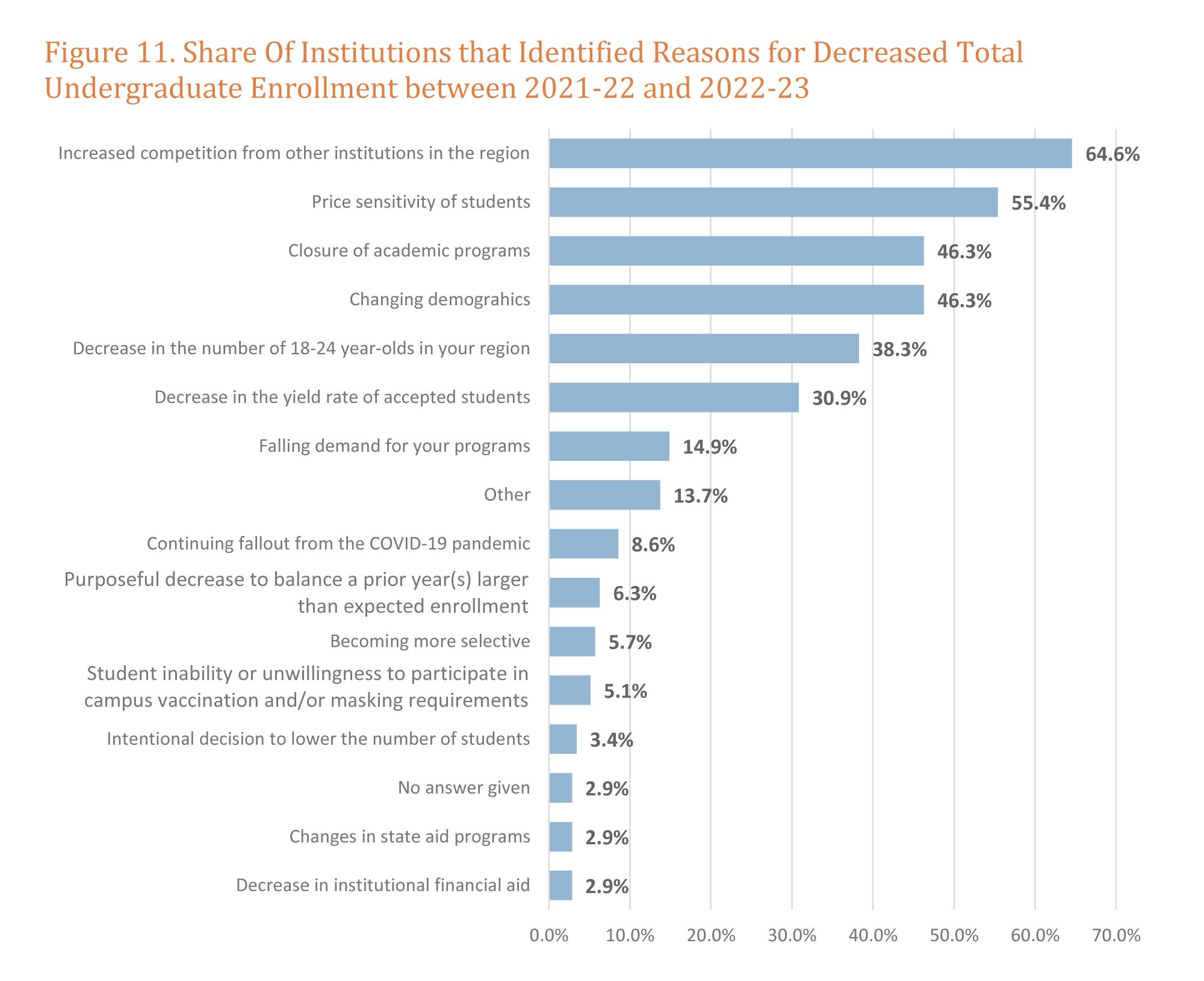

The report also asked colleges to identify reasons for undergraduate enrollment declines. Of those that reported a decrease in enrollment, the most common reason cited was increased competition from other colleges in the region, at 64.6 percent. After that, 55.4 percent named student price sensitivity, 46.3 percent each blamed the closure of academic programs and changing student demographics, 38.3 percent cited the declining number of regional high school graduates, 30.9 percent pinned it on a decrease in the yield rate of accepted students, and 14.9 percent attributed the decline to falling demand for the college’s programs.

Some observers noted that while the rising tuition discount rate has helped make education more accessible to low-income students, colleges have also leveraged that strategy to keep enrollment stable, offering steep discounts across income levels even as they continue to raise sticker prices each year.

“What has happened over the course of probably the last 15 years is more of that money has been directed toward upper-income families rather than lower-income families, as a means of staying competitive in what has been a highly competitive environment,” explained Bill Hall, founder and president of Applied Policy Research Inc., a consulting firm based in Minnesota.

Hall added that demand for higher education is stagnant, pointing to a variety of factors including the decline in college-going rates and workforce needs luring high school graduates straight into the job market. Those struggles, and a looming demographic cliff, mean colleges are unlikely to see an explosion in applicants, suggesting they will have to find other ways to increase enrollment.

“If you want to grow, you’re going to have to do something to induce additional yield,” Hall said.

For now, the answer for many colleges seems to be to throw money—in the form of institutional aid—at the enrollment problem. And come next year, that may mean a new record high for tuition discounting, which continues its steady ascent as colleges compete for fewer students.