You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

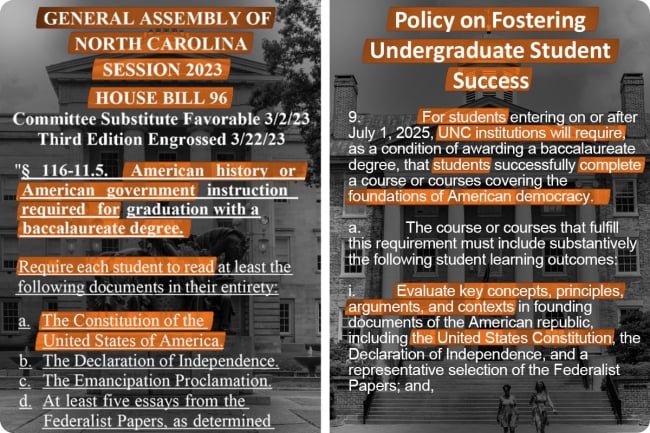

Some provisions of North Carolina lawmakers’ proposed REACH Act compared with the UNC system’s new policy.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Carol M. Highsmith/Library of Congress | North Carolina General Assembly | Eros Hoagland/Getty Images | University of North Carolina System

States have long imposed specific standards on what K-12 public schools must teach. During the Obama era, the Common Core movement even tried to establish nationwide standards for math and English at these grade levels.

But legislators and other state officials generally haven’t told faculty members at public colleges and universities what they have to teach in their classrooms. “Higher ed has more explicit traditions of academic freedom than K-12,” said James Grossman, executive director of the American Historical Association. “K-12 teachers are, in essence, told what to teach by the state, by the school board … nobody is supposed to tell a professor what to teach.”

In North Carolina, however, Republican lawmakers have recently attempted to tell undergraduate students what they have to read. Last year, in a nearly party-line vote (one Republican voted nay, one Democrat yea), the state’s House of Representatives passed the Reclaiming College Education on America’s Constitutional Heritage (REACH) Act.

The bill, still pending before the majority-Republican state Senate, would require all students seeking bachelor’s or associate's degrees in North Carolina’s public universities and community colleges to complete “at least three credit hours of instruction in American history or American government that provides a comprehensive overview of the major events and turning points.”

Requiring an American history course wouldn’t be unique to North Carolina. Texas does so. But the REACH Act would reach deeper than a course requirement by requiring students, as part of the course, to read “in their entirety” specific documents: the U.S. and North Carolina Constitutions, the Declaration of Independence, the Emancipation Proclamation, the Gettysburg Address and Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail. Students would also have to read at least five essays from the Federalist Papers, chosen by the instructor.

The bill would also dictate final grade details. At least a fifth of students’ grades would come from an exam focusing on the documents’ “provisions and principles,” their authors’ perspectives and “the relevant historic contexts” when they were written. The bill said the boards overseeing the universities and community colleges could remove chancellors and presidents for failure to comply.

Much has been written about legislative efforts in states such as Florida and Alabama to curtail teaching about certain subjects in higher education, especially race and related “divisive concepts” that conservatives associate with diversity, equity and inclusion. But here was a state proposing to tell faculty members what to teach, not what not to.

The REACH Act has been pushed by the conservative American Council of Trustees and Alumni (ACTA) and a U.S. Marine Corps judge advocate, Captain Jameson Broggi. Broggi has interned for The Heritage Foundation and Republican senators Tim Scott and Jim DeMint, and the Claremont Institute named him one of its 2023 John Marshall Fellows, but he said he’s advocating for the bill on his own accord. (This paragraph has been corrected to reflect that Broggi didn’t work or intern for Claremont.)

In 2021, Broggi and ACTA succeeded in passing another REACH Act in Broggi’s native South Carolina. Among that law’s few differences with the North Carolina bill, the “R” in reach stands for “Reinforcing,” not “Reclaiming.”

In North Carolina, nearly 700 University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill faculty members signed a letter objecting to the REACH Act crossing the state line. They wrote that the bill “violates core principles of academic freedom” and “substitutes ideological force-feeding for the intellectual expertise of faculty.”

In The Charlotte Observer, Kathleen DuVal, a Chapel Hill U.S. history professor, wrote that before they go to college, “the vast majority of our students have already been taught, as the State Board of Education’s standards require, ‘how the judicial, legal and political systems of North Carolina and the United States embody the founding principles of government.’” DuVal wrote that most North Carolina college students “are already active citizens,” and the bill “is an insult to them as well as to their high school and college teachers.”

The fact that the REACH Act still hasn’t passed in North Carolina might be due to what some UNC system faculty members did next. Concerned about the REACH Act, they worked with the UNC Board of Governors—which oversees all public four-year degree granting institutions in the state, even those without the UNC moniker—to pass a board policy last month. It looks like the bill, but has major differences.

Will the board’s policy assuage Republican lawmakers—or invite more attempts by them to intervene in North Carolina, and other states? Those outside the General Assembly aren’t mollified. In The Carolina Journal, a publication of the conservative John Locke Foundation, Broggi wrote that “while at first this may seem like a step towards correcting UNC’s lack of civics education, a second look suggests it could be a strategic maneuver to dissuade the legislature from passing the robust REACH Act.”

A Precedent for Compromise, or Interference?

Starting in July 2025, the new North Carolina policy says incoming bachelor’s-degree seekers will be required to study the same documents the REACH Act would require, minus the North Carolina Constitution and minus the requirement to read any of the documents in their entirety.

But the biggest divergence from the bill is that it doesn’t require a whole course in American history or government. Students could satisfy the requirement to study these documents as part of courses that are mostly unrelated to the U.S. The policy further allows the UNC System president to issue “exemptions … for a student’s prior learning.”

Wade Maki, chair of the statewide UNC Faculty Assembly and a principal lecturer of philosophy at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, said the UNC System office called him late in the summer, after the REACH Act stalled, asking him to work with other faculty members on an alternative. That became the new policy.

Maki said students seem to know less about the U.S. than they did decades ago, but he was concerned about the REACH Act’s practical consequences. He said its requirement for all bachelor’s degree seekers to take a whole American history or government course would’ve forced universities to create many more class sections.

“There are not that many historians just sitting around with nothing else to do,” Maki said. He said the UNC School of the Arts, one of the system’s institutions, has no history or political science department. “There were huge implications to this bill that those pushing it probably hadn’t thought through,” Maki said.

Broggi has publicly criticized Maki for leaving some requirements out of the policy, but he’s also received blowback from faculty members for capitulating to external pressure. “I’ve been hit from both the right and the left for this policy, from ‘we shouldn’t have done anything at all’ to ‘it’s not strong enough,’” Maki said. He said the policy prevented the legislature from passing the REACH Act: “We have a supermajority Republican legislature heading into an election year looking at a requirement to study America, you tell me how that was going to go.”

“Every part in the system has a role to play and we were given a chance to play our role and we did that,” Maki said of himself and the other faculty members who helped create the policy. And, with the requirement now in board policy, not law, Maki noted it can be changed in the future, based on student performance and faculty feedback, without going through the “herculean effort” of changing a law.

“We are keeping the politics as far away from higher ed as we can through our partnership and, if nothing else, I would like to see faculty in other states and administrators in other states try to model what we’re doing,” Maki said. He said this “partnership” among faculty members and the UNC System leaders showed the General Assembly “that they don’t need to intervene, that we are responsive to concerns—but that faculty control the curriculum.”

Sean Colbert-Lewis Sr., an associate professor of history and education at North Carolina Central University, worked alongside Maki on the policy. Colbert-Lewis said he’s only taught high school students for the past three years as part of an early-college program, and he’s been left with concerns about students’ civics competency. Despite their having previous history instruction, he said some have come to him not knowing the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution are called the Bill of Rights.

However, Colbert-Lewis said the REACH Act could’ve endangered academic freedom. He said that he, Maki and others showed, through working on the policy, that faculty members can be partners “without having the need for direct political intervention.”

Other faculty members disagree with the policy and what it may herald. Jay Smith, president of the North Carolina Conference of the American Association of University Professors and a University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill history professor, said “the development of this particular policy had virtually no faculty input, a tiny committee of five faculty were consulted at some point.”

Smith also said that faculty members trying to preempt a bill by doing the legislature’s “dirty work” for it “just doesn’t seem to get us very far.” He said lawmakers influencing the curriculum “should be regarded as a line in the sand that we don’t allow them to cross.”

He also expressed concern about the precedent set. “Once they’ve done that in a couple of instances, where do they stop?” he asked. “And how do we muster the authority to get them to stop?”

Continuing to Reach

While the policy may have been passed to fend off lawmakers, the effort to pass the REACH Act will continue. Broggi didn’t give up in South Carolina.

“I started working on it on my own as an undergraduate student at the University of South Carolina in 2013,” Broggi wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed. “It took me eight years of working on it before it passed in 2021.” In The Carolina Journal, Broggi wrote that the South Carolina REACH Act succeeded in updating “a 100-year-old South Carolina college civics law that many colleges were not following.”

Now he’s stationed at a U.S. Marines base in North Carolina, and he’s continued the fight there.

“The [UNC] Board of Governors’ recent move is a civics requirement in name only,” Broggi told Inside Higher Ed in an email. “This is because the board’s proposal does not require a three-credit-hour class, does not require the class to be in American government and does not even require that students read the U.S. Constitution for themselves … the board adopted its empty proposal to appear to do something while not substantively changing anything.”

The UNC system provided some emailed information, but not an interview for this article.

ACTA has also crossed the border and lobbied in North Carolina. Michael Poliakoff, the ACTA president who previously founded the classics department at the conservative Christian Hillsdale College, said “we will help in any way we can” to pass the North Carolina REACH Act.

Poliakoff said the board policy is a good step but has “wiggle room.” For instance, Poliakoff noted it doesn’t require students to read the founding documents in their entirety.

“This is not onerous reading,” Poliakoff said.

“This is not something that is new or radical,” Poliakoff said. “When the faculty fail, and they have failed, to set the kinds of curriculum requirements that would have done this a long time ago, then it falls to the elected representatives that have under their purview the public universities to remedy that. They’re not intruding into classrooms … The faculty should have felt real shame that they don’t already have such a requirement.”

While it hasn’t yet left the Carolinas, the REACH Act could inspire other bills throughout the country. Broggi’s and ACTA’s work to require students to read the founding documents in their entirety seems to have inspired the Civics Alliance, a group sponsored by the conservative National Association of Scholars. It now has model higher education legislation on its website that would require students to read the same national REACH Act documents, plus the 1876 Declaration of Rights of the Women of the United States.

“Our model bill drew upon existing statutes, including the South Carolina REACH Act,” said David Randall, director of research with the National Association of Scholars.

Both ACTA and the Civics Alliance have been critical of The New York Times’ 1619 Project, which focuses on the continuing legacy of slavery in American history. The Civics Alliance’s website condemns it as calling “for ‘reframing’ all of American history (and civics) as the story of white supremacy and black subjection.” The Civics Alliance says “identity politics” and “critical race theory, multiculturalism and so-called ‘antiracism,’” threaten to “ruin our country by destroying our unity, our liberty and the national culture that sustains them.”

But Poliakoff said “I think it’s a grave mistake to see the concern about American history and American government as a conservative initiative … this is something that concerns every American, regardless of party.”