You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

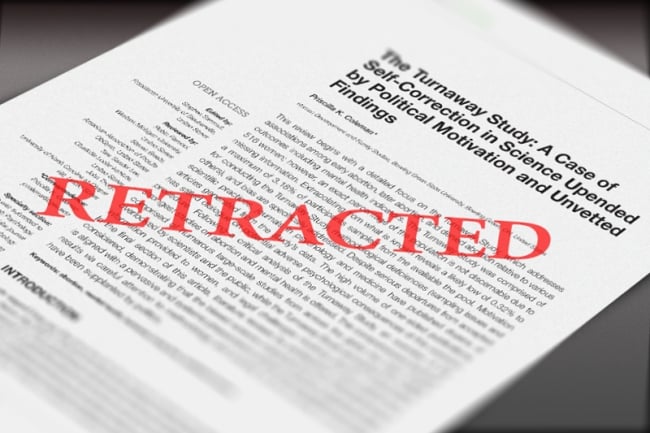

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison | Document courtesy of Priscilla K. Coleman

June 2022 saw the U.S. Supreme Court end the federal constitutional right to abortion, beginning a new era of litigation over whether individual states would preserve that right.

The same month also saw a new chapter in arguments over publications by Priscilla K. Coleman, a retired Bowling Green State University professor of human development and family studies whose work was cited in an amicus brief in that Supreme Court case. Coleman criticized the “turnaway” study—acclaimed research that buttresses arguments for abortion rights—while some turnaway study researchers have criticized Coleman’s research.

In the turnaway study, demographer Diana Greene Foster and her team identified hundreds of women who’d sought abortions and kept in touch with them for five years. Some of the women in the group had been turned away (hence “turnaway”) from abortion providers for being up to three weeks over the gestational limit, so Foster was able to draw comparisons over time between patients who got abortions and those who wanted them but were denied.

On June 17, 2022, Frontiers in Psychology published Coleman’s critique: “The Turnaway Study: A Case of Self-Correction in Science Upended by Political Motivation and Unvetted Findings.”

Priscilla K. Coleman

The same day, researchers, including some involved in the turnaway study, wrote to The British Journal of Psychiatry (BJPsych) requesting a retraction of one of Coleman’s papers there: a 2011 meta-analysis that claimed to reveal “a moderate to highly increased risk of mental health problems after abortion.”

Coleman says five of the 17 signatories of the retraction request were turnaway study researchers.

Foster, a signatory, provided Inside Higher Ed a copy of the retraction request with the names of the other signatories removed, saying they hadn’t given their OK to be named. She wrote in an email that the timing was “definitely a coincidence. I only saw her [Frontiers] paper the next day.”

“These errors render the results of this study meaningless and the conclusions invalid,” the request to retract the BJPsych paper said. The request alleged multiple issues.

“Coleman’s conclusion about the impact of abortion on mental health conflicts with numerous methodologically more rigorous studies [18–27],” it said. “It also contradicts with the current scientific consensus and conclusions reached by major professional associations, including the Royal College of Psychiatrists, the American Psychological Association and the American Psychiatric Association [28–30].”

“These inaccurate results continue to misinform public policy and lawmakers, negatively impacting pregnant people and their families,” it said.

Foster is a professor in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences at University of California, San Francisco. Antonia Biggs, who said she also signed, is an associate professor there.

“From the perspective of mental health, it’s more harmful to deny someone a wanted abortion than to allow them to get the abortion that they want,” Biggs said.

In a 43-page defense of her BJPsych paper, Coleman provides what she calls “Information suggestive of conflicts of interest and bias for 16 out of 17” signatories. She accused signatories of a “pro-choice bias.”

“Every one of the signatories is a highly experienced researcher and they all know their accusations are spurious,” she wrote. “Their motivation in contacting you is not about the science; it is about discrediting me as a researcher and expert witnesses for political reasons. My meta-analysis has informed many of the opinions I have offered under oath in litigation in the United States.”

The debate since June 2022 over Coleman’s work has ended up in very different places in Frontiers and BJPsych.

After Coleman’s critique of the turnaway study appeared in Frontiers, readers pointed out that Coleman’s article had been edited and peer reviewed only by scientists with antiabortion views. The editor and three out of four reviewers were affiliated with one antiabortion group in particular.

Biggs, a turnaway study researcher, and nine others wrote to Frontiers defending the turnaway study. Biggs said that commentary, unlike the BJPsych letter, wasn’t a retraction request.

Frontiers published that commentary Dec. 2, and by the end of the month it retracted Coleman’s critique.

“Undisclosed competing interests were brought to our attention, which undermined the objective editorial assessment of the article during the peer review process,” the brief retraction note says. “Frontiers conducted a post-publication assessment of the article, including consulting with independent expertise, which concluded that the article does not meet the standards of publication of Frontiers in Psychology.”

That retraction was despite Coleman’s lawyers getting involved—she said they threatened a defamation suit to get Frontiers to remove an editorial expression of concern saying the paper was under investigation, but Frontiers didn’t, and it eventually retracted the article.

Coleman is currently suing, but she declined to provide her legal filings.

In emails to Inside Higher Ed, a Frontiers spokeswoman wrote that “both an urgent injunction and interim measures have been denied by the Swiss court … I am afraid we cannot provide any further legal details at this time, but all claims brought by Priscilla Coleman against Frontiers before Swiss courts have so far been rejected.” Frontiers’ editorial office is in Switzerland.

BJPsych, on the other hand, backed down on even adding a notice of concern after Coleman got lawyers involved, Coleman said.

When the BJPsych retraction request came through, Dr. Kamaldeep Bhui, then editor in chief, tasked a panel with investigating the article, said Dr. Alexander Tsai, a Harvard Medical School associate professor who said he was on that panel. The BMJ and Newsnight reported earlier on the retraction controversy.

Dr. Tsai told Inside Higher Ed the panel recommended retraction after a roughly four-month investigation, but the Royal College of Psychiatrists, which owns the journal, said that wouldn’t happen. Dr. Tsai said he and an unknown number of other editorial board members resigned in response.

“Given this disregard of our expert opinion under legal threat, I believe that editorial independence is no longer being afforded to the journal and therefore have no choice but to resign my editorial board appointment,” Dr. Tsai wrote in his May resignation letter to the Royal College’s president.

“I can no longer fulfill my key responsibilities: I do not believe I can be an effective ambassador for the journal, because I cannot in good conscience recommend that my colleagues submit their best work to the journal; I do not believe I can provide input into strategy or peer review, because the handling of our panel’s recommendations demonstrates that such input is not appropriately regarded; and I no longer believe that the college’s values of courage, respect and excellence are being promoted through its publication of journal content,” Dr. Tsai wrote.

He told Inside Higher Ed Thursday that “I do not think that readers will respect a journal if it is perceived to be a house organ.”

Dr. Bhui, whom Dr. Tsai said had been editor in chief for the past decade, is no longer in that position. He didn’t return Inside Higher Ed’s requests for comment Friday.

The Royal College didn’t provide an interview Friday. It provided Inside Higher Ed the statement it wrote in response to the BMJ and Newsnight coverage.

In the statement, the college notes that BJPsych published the Coleman article, “Abortion and mental health: quantitative synthesis and analysis of research published 1995–2009,” in 2011. The college said there were complaints then, but the then BJPsych editor investigated between 2011 and 2012 and decided against retraction.

“He did however decide that the letters critiquing the article could be published and posted online with the article,” the college said. “Last summer, over a decade later, we received the complaint from some of the original complainants, which was very similar in substance to the original complaints from back in 2011.”

“After careful consideration, given the distance in time since the original article was published, the widely available public debate on the paper, including the letters of complaint already available alongside the article online, and the fact that the article has already been subject to a full investigation, it has been decided to reject the request for the article to be retracted,” the college said. The statement doesn’t make clear who actually made the decision not to retract.

“We now regard this matter as closed,” the statement said.

Dr. Tsai, who is also a psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital, declined to release the panel’s report suggesting retraction or say who else was on it. He said his colleagues are worried Coleman will sue them.

“We just have very scared colleagues,” Dr. Tsai said.

He said the June 2022 retraction request that spurred the panel inquiry was in response to a BJPsych editorial the previous month that announced the new Royal College of Psychiatrists journals’ Research Integrity Group. Biggs said that was true.

“My only interest is ensuring the proper scientific record and research integrity and high-quality science,” Biggs said, “so I think that’s the only goal here, is to ensure that we have good evidence out there.”

“The motivation was really this creation of this research integrity group, and it’s not an attack on a person,” she said.

“The issue is not the findings,” she said. “The issue is the work.”