You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

With a near-record 113,000 postgraduate research students based in the U.K., including 46,350 foreign Ph.D. candidates, Britain’s doctoral education landscape would seem to be thriving. Buoyed by an extra 109 million pounds ($119 million) from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) to support Ph.D. and midcareer researchers in 2023–24, and Horizon Europe membership secured, there might appear little cause for concern.

But there are signs that things are not as rosy in U.K. doctoral education as some imagine. In November, the Student Loans Company noted the “first potential yet small decline in the take-up of postgraduate doctoral student loans,” with sums borrowed in 2022–23 down by 12.3 percent.

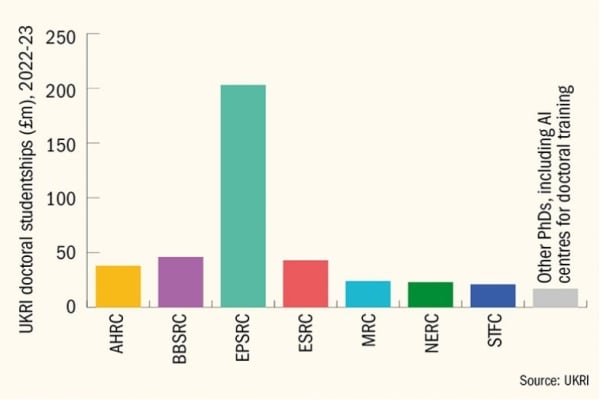

There are also indications that the number of funded Ph.D. studentships will not be as plentiful over the next few years. The biggest single funder of Ph.D.s—the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, which sponsored nearly half of the 4,900 UKRI-backed doctoral students who began their studies in 2022–23—announced last year that the number of its Centers for Doctoral Training would fall from 75 to “about 40” starting in 2024, leading to about 1,750 fewer funded places over the next five years.

In addition, the Arts and Humanities Research Council is reducing its Ph.D. studentships by nearly a third, from 425 to 300 per year by the end of the decade, and the Wellcome Trust is severely reducing its support for Ph.D. students under its new strategy to focus on longer grants for early- and midcareer scientists.

Things could get a lot worse in the next few years, with the Institute for Fiscal Studies warning that tax cuts announced in Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt’s autumn statement would lead to budget reductions of about 3.4 percent a year in “unprotected departments,” one of which might be the new Department for Science, Innovation and Technology.

“It’s going to be tough going with an election and a spending review, whichever party wins,” predicted Rory Duncan, UKRI’s former director of talent and skills, who is now pro vice chancellor, research and innovation, at Sheffield Hallam University.

If universities were forced to tighten research spending, support for Ph.D. students could be an early casualty, because doctoral researchers—while sometimes seen as a source of cheap labor—are a big cost center for institutions, explained Duncan. “If you look at Trac [Transparent Approach to Costing] data, the cost recovery for doctoral students is very low—the lowest for any type of research activity,” he said, pointing to data that showed U.K. universities incurred losses of £1.4 billion ($1.7 billion) educating Ph.D. students in 2021–22, claiming back just 46.6 percent of the cost of training researchers.

In the Money: Ph.D. Funding

UKRI

Thanks to U.K. universities’ success in attracting higher-paying international students, the sector has been able to cover such losses—which amount to $6.3 billion (£5 billion) a year for research over all—but that balancing act is “becoming much more challenging due to government rhetoric” over foreign students, continued Duncan. “There is huge pressure on the research sector, and it’s becoming harder and harder to do research—which includes supporting Ph.D. students,” he said.

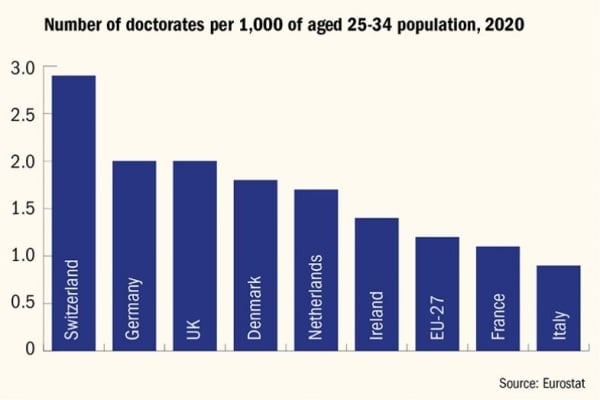

That will be bad news for the U.K.’s “science superpower” ambitions, as the country’s innovation model had leaned heavily on having high Ph.D. numbers, Duncan said. “For many years the U.K. has been a leader for investing in Ph.D. training—it’s always been a top-three nation, alongside Germany and the U.S., for Ph.D.s. Others, like Japan, have taken different routes and changed their support to focus on midcareer scientists, which has a very detrimental impact on research quality,” he added.

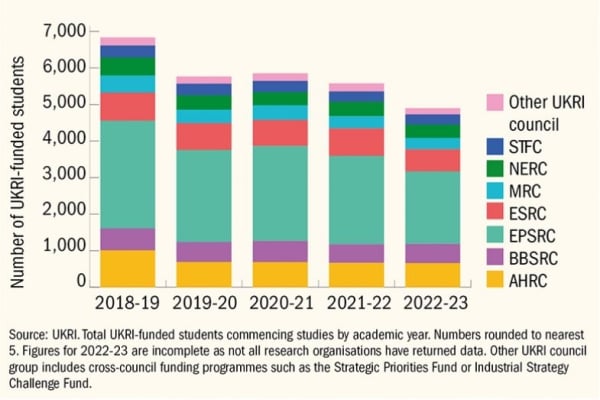

But the level of the U.K.’s investment in Ph.D. training seems to be waning—at least, if judged by the numbers of doctoral students trained in recent years. A recent Freedom of Information request by Times Higher Education found the overall numbers of doctoral students starting UKRI-funded training fell from 6,835 in 2018–19 to 5,580 in 2021–22—an 18 percent drop—with reported figures for 2022–23 lower still at 4,900, though UKRI said this tally could increase as universities continued to submit data for that year. The decline in U.K. student numbers was even sharper, falling from 4,815 new candidates in 2018–19 to 3,420 in 2021–22—down by 29 percent—and to 2,840 in 2022–23.

Wrong Numbers: Falling Ph.D. Figures

UKRI

For Douglas Kell, a former executive chair of the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, such reductions are distinctly at odds with the government’s desire to bring an extra 150,000 researchers into the workforce by 2030.

“Cutting funded Ph.D. numbers under any circumstances, especially in a knowledge economy, is simply short-termist and absolute madness,” said Kell, now based at the University of Liverpool, who observed that these “further cuts extend those that have already been going [on] under this administration for more than a decade. We need massive increases in those who are technically and intellectually qualified, not cuts.”

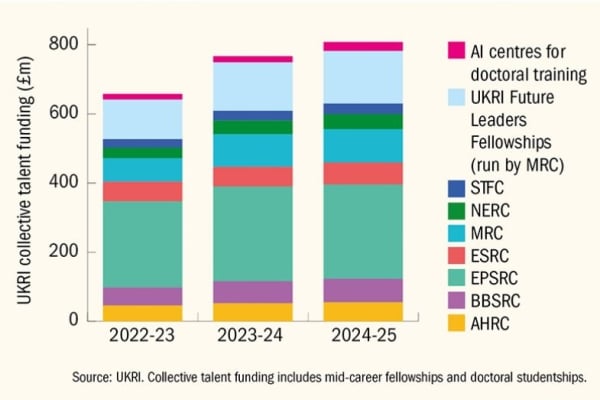

However, UKRI’s collective talent funding—which supports both Ph.D. studentships and midcareer fellowships—is due to increase by only 5 percent in 2024–25, so funded places could “go down in the absence of additional investment,” warned Duncan, citing the continued need to increase tax-free doctoral stipends in line with inflation.

Group Interests: Talent Funding

The hefty increases to UKRI’s stipend—£18,622 ($23,672) in 2023–24, up 20 percent from 2021–22—still might not be enough to fix a bigger issue facing doctoral education, according to Robert Insall, professor of computational cell biology at UCL. “A lower proportion of the most brilliant students are doing Ph.D.s—those who are really ambitious and who might become future leaders in their field,” said Insall. “Even if you increased the stipend by 10 percent again, it might not be enough to make it acceptable. Its level was acceptable a few years ago, but now it just isn’t.”

The gloom hanging over U.K. higher education and research might explain why “the attractiveness of a Ph.D. has gone downhill” for highfliers who might have previously considered a research career in academia, continued Insall. “The government is not selling British academia and the media is painting it as a very troubled place, so students and potential Ph.D.s see that,” he said.

For its part, UKRI seems alert to the challenge of keeping the Ph.D. attractive, with plans for a new “core offer” around professional and career development set to be unveiled this year. According to UKRI’s chief executive, Dame Ottoline Leyser, this would “provide consistent talent offers that are still responsive to the needs of individuals and disciplines” and “strengthen the crucial link between career diversity and excellent research and innovation, better enabling people to follow their ideas across disciplines and sectors.”

Concerns over the direction of travel remain, but the fact that the U.K. is still a key destination for postgraduate students, behind only the U.S., suggests its doctoral model is far from broken, said Giulio Marini, visiting professor of education at the University of Hong Kong, whose research has focused on how Ph.D. graduates fare in global job markets. “The U.K. is highly attractive, and it seems it will remain so—Brexit was not helpful, but now that the U.K. is back into European funding schemes, I would not worry too much,” he said.

However, the country’s international popularity among foreign Ph.D. students might serve U.K. universities but not the U.K. economy in the long run if restrictive immigration rules push them to leave after a few years, warned Marini. “If Ph.D.s do not continue to live in the U.K., their economic contribution will be limited. In that situation, U.K. universities are really ‘making brains for other countries,’ which is not good policy.”

Is There a Doctor in the House? Ph.D. Population