You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A new law will require North Carolina’s public institutions to change accreditors every 10 years.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Allison Joyce/Getty Images

North Carolina colleges and universities will be required to change accreditors every cycle, according to a new bill that was passed amid a flurry of other legislation and signed into law last week.

Lawmakers slipped the requirement to change accreditors—which follows similar legislation passed in Florida in 2022—into a bill that made a series of statutory changes, such as requiring the state’s high school students to pass a computer science course to graduate and requiring pornographic websites to verify the ages of users. Tucked among the changes was a new rule barring state colleges and universities from using the same accreditor for consecutive cycles.

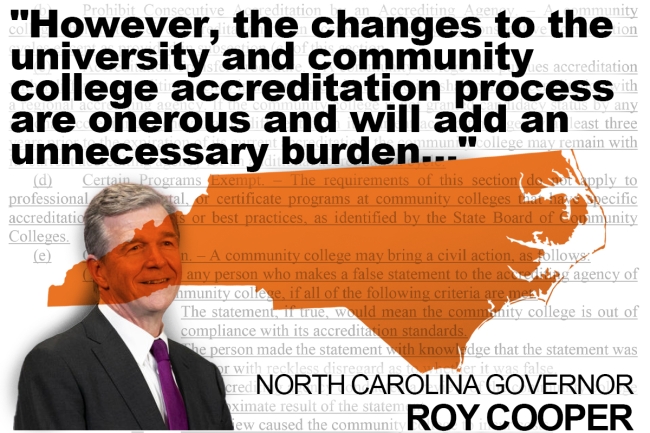

A similar bill requiring state institutions to switch accreditors passed the North Carolina Senate in May but failed to win in the House, leading Republicans to seek an end around to force such changes. The new bill—HB 8—passed with no debate during a late legislative session dominated by state budget discussions. It has received scant media attention, though North Carolina’s Democratic governor, Roy Cooper, raised concerns about the impact of changing accreditors even as he signed the bill into law.

An End Around on Accreditation Changes

North Carolina lawmakers have been seeking to change accreditation practices at least since February, when the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges—which accredits numerous public institutions in the state—raised concerns about a University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill plan to fast-track a new School of Civic Life and Leadership. SACS president Belle Wheelan sent a letter to UNC’s board seeking more information on the plan.

Wheelan reportedly questioned the institution’s compliance with SACS’s accreditation principles, raising concerns based on media reports about the lack of faculty input for the new school.

In response, Republican lawmakers crafted Senate Bill 680. While that piece of legislation cruised through the Senate in May—passing 32 to 18, with only one Democrat voting in favor—the legislation did not advance in the House. Undeterred, Republican state senator Michael V. Lee tucked the changes into statutory updates that easily passed in the General Assembly on a vote of 102 to 8. Governor Cooper then signed the bill into law.

The bill was simply titled Various Statutory Changes.

In a statement last Monday, Cooper noted the importance of parts of the legislation, such as the computer science requirement and age verification for online pornography. But he also expressed concerns, calling the changes to accreditation “onerous.” He suggested such legislation “will add an unnecessary burden and increase costs for our public higher education institutions,” suggesting that “the General Assembly should reevaluate these requirements.”

The governor’s office did not respond to a request for comment from Inside Higher Ed.

North Carolina’s new accreditation law prohibits higher education institutions from having the same accrediting body for “consecutive terms,” meaning that colleges must switch each cycle. A provision of the law also allows state institutions to “bring a civic action” against individuals who make false statements to accreditors, an apparent attempt to deter meddling critics. Or, as free speech group PEN America summarized SB 680, “A public college or university may hold liable any individual who willfully lied about the institution and, on the basis of that lie, the accrediting agency conducted a review that caused the institution to pay costs.”

Paul Gaston III, an emeritus Trustees Professor at Kent State University and an expert on accreditation, noted that while the new law is similar to Florida’s, it does differ slightly.

For one thing, a college would be allowed to stay with its current accreditor for consecutive cycles if it is “unable to secure candidacy status” from another accreditor three years before the current accreditation expires, Gaston said by email. But if an institution was well into a 10-year cycle, “it could be difficult for it to qualify for candidacy prior to the seventh year of its term. Thus it would be allowed to remain with its current accreditor for one more cycle.”

But in other ways, North Carolina’s new legislation seems to go further than Florida’s.

For instance, the new accreditation law tasks the Board of Governors with establishing “a Commission to study alternatives to the current process by which institutions of higher education are accredited and shall invite stakeholders, including stakeholders from other states, to participate.”

By contrast, Florida is not questioning the process of accreditation—“at least not yet,” Gaston pointed out—but is simply prohibiting “continuity from one accreditation term to the next.”

Gaston also flagged two “slip-ups” in the legislation. First, he noted a reference to “regional” accreditors, a term that is now outdated since changes to federal rules during the Trump administration lifted geographic restraints on accrediting bodies, allowing them to operate beyond their historic regions. And the text of the bill lists six “regional” accreditors as acceptable overseers for public institutions. Given that state community colleges are also required to change accreditors, Gaston said that the Accrediting Commission for Junior and Community Colleges should be included on that list.

Following Florida’s Lead

Wheelan—whose scrutiny seemed to drive the legislative push for accreditation changes in both Florida and North Carolina—offered a brief statement to Inside Higher Ed via email.

“As you know, accreditation serves a valuable public good to ensure quality and integrity within our member institutions,” she wrote. “A peer driven and member determinative process, accreditation ensures the public, that our member institutions comply, and abide by a set of standards. If information comes to our attention that suggests that an institution may be out of compliance with those standards, we are required to make an inquiry as to what’s going on.”

The University of North Carolina system did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Though the changes to accreditation are new, the conflict over the issue has been playing out for months. Dueling op-eds have portrayed both the prior status quo and the changes to accreditation as problematic. Proponents of the change have cast it as a necessary counteroffensive against an overstepping accreditor; opponents argue that it will allow the Board of Governors—appointed by North Carolina’s Republican-dominated Legislature—to shop around for an accrediting body that will be more hands-off on issues such as academic freedom.

(Lee, the architect of the new accreditation law, did not respond to a request for comment.)

The surprise passage of the bill seemed to catch opponents off guard. Coalition for Carolina, a nonprofit organization comprised of faculty, staff, students and others connected to the UNC system, held a webinar in May warning against sweeping changes to accreditation. Experts argued they would be costly and unnecessary.

In a website post on Thursday—three days after the legislation had been signed into law—Coalition for Carolina raised alarm that the bill had passed “with no notice and no debate.”

In a statement sent to Inside Higher Ed, Coalition for Carolina called the change “ill-advised, ill-conceived and hastily passed” and suggested it would lead to “serious harm to the University of North Carolina—as well as to all colleges, universities and community colleges in North Carolina.” The group added that changes will lead to “higher costs and lower quality” and that “the General Assembly should reverse this rash, harmful and damaging action.”

While the ink is barely dry on North Carolina’s new law, Florida’s institutions are already making moves to decamp from SACS for other accreditors. To date, seven of Florida’s 40 public institutions—all of which will be required by state law to change accreditors when their current terms end—have requested approval from the Department of Education to do so. They are: College of the Florida Keys, the College of Central Florida, the University of Central Florida, Florida SouthWestern State College, Florida Polytechnic University, Chipola College and Palm Beach State College.

Accreditor changes are expected to come with significant investments of time and money. An estimate last year found the cost of switching accreditors could run from $11 to $13 million a year; the annual expense of maintaining accreditation is about $250,000, according to Florida Board of Governors documents. Potential costs for North Carolina are not immediately clear.

Gaston suggested the new law imposes an additional financial cost on public institutions.

“I would observe that in both NC and Florida, the legislative action imposes a financial and operational burden on public institutions that private ones are spared. The costs of seeking candidacy—both the fees that must be paid and the staff time that must be devoted to the effort—are considerable. So while its principal neighbors [North Carolina State University and UNC Chapel Hill] must identify the resources to meet this mandate, Duke [University] is spared,” Gaston wrote.