You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Warning: The results of Inside Higher Ed’s new Survey of College and University Presidents, published today, may leave you with a serious case of whiplash.

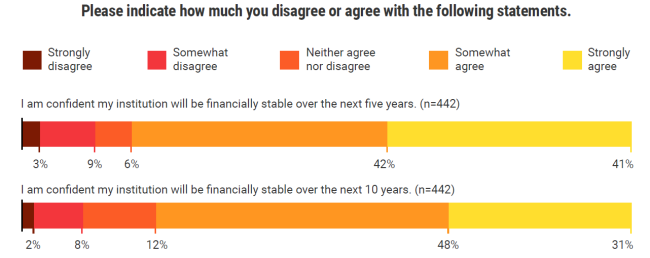

Many of the headline findings from the survey, the 13th annual iteration, show campus leaders to be quite optimistic about the state of their institutions and of higher education as a whole. Almost eight in 10 respondents agree (31 percent strongly) that their institution will be financially stable over the next decade. Presidents are twice as likely to say their institution will be better off next year than it is now (58 percent) as to say they expect next year to be worse (26 percent). Only one in five is worried about the rate of faculty and staff turnover, and more than two-thirds agree that their institution has the capacity to meet the mental health needs of undergraduate students.

“We’ve got this,” the campus leaders seem to be saying.

Other findings of the survey, conducted in conjunction with Hanover Research, reveal that campus chief executives fully recognize the strains and pressures prompting many observers to question the viability of hundreds of institutions and to worry about the state of higher education generally.

More than a quarter of presidents (27 percent) think their institution should consider merging with another college or university in the next five years, and about seven in 10 concur that “my institution needs to make fundamental changes in its business models, programming and other operations.”

Three-quarters agree (35 percent strongly) that the “perception of colleges as places that are intolerant of conservative views is having a major negative impact on attitudes about higher education.” And nearly six in 10 agree that “public doubts about the affordability of higher education are justified.”

More on the Survey

Inside Higher Ed’s 2023 Survey of College and University Presidents was conducted by Hanover Research. The survey included 442 presidents from public, private nonprofit and for-profit institutions, for a margin of error of 4.24 percent. A copy of the free report can be downloaded here.

On Saturday, April 15, Inside Higher Ed will conduct a session on the survey at the American Council on Education annual meeting in Washington.

On Wednesday, May 10, Inside Higher Ed will present a free webcast to discuss the results of the survey. Please register here.

The Inside Higher Ed Survey of College and University Presidents was made possible by support from TimelyCare, Jenzabar, EY Parthenon and Ready Education.

Those findings—along with others showing that presidents remain skeptical about the quality of online courses, strongly reject public doubts about higher education’s value and ability to prepare graduates for work, and overwhelmingly believe that race relations on their own campuses are either excellent or good—suggest that campus leaders are “perhaps operating more on hope than on strategy,” said Kevin R. McClure, associate professor of higher education at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington’s Watson College of Education.

He and several others who reviewed the data said they were struck by the presidents’ optimism in the face of strong headwinds in the form of enrollment declines, financial strain, unprecedented political intrusion and growing public questioning of higher education’s performance.

Inside Higher Ed’s annual survey is, more than anything, a snapshot of how the men and women charged with leading America’s colleges and universities are viewing their institutions, the issues they’re facing and the higher education ecosystem writ large. It is unsurprising, McClure and others said, that presidents may have an upbeat perspective, because as leaders they “see all of the hard work and good things happening” on their campuses and assume that “some of the ideas you’re putting into place will have legs” and create positive outcomes.

But it’s problematic if presidents’ roles as chief cheerleader and advocate lead them to play down the real pressures bearing down on many of their institutions, as Rick Staisloff said he worried the results suggest. “If the opinions expressed here were true, higher education could continue doing what it is doing, the way it is doing it,” Staisloff, founder and senior partner of rpk Group, a consultancy, said via email. “I would not advise any president in the United States today to carry their current model forward as is.”

The Financial Picture

A key element of Inside Higher Ed’s annual survey of college presidents is a set of questions about institutions’ financial states and trend lines. Just as a consumer confidence survey reflects how Americans feel about the economy rather than the underlying conditions shaping it, the results of Inside Higher Ed’s survey reflect presidents’ sentiments about where their institutions are. Because the survey is anonymous, the leaders in theory are sharing their unvarnished views.

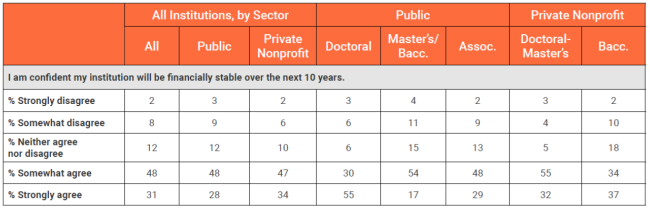

Their answers show the presidents over all to be quite upbeat, with about eight in 10 expressing confidence in their institutions’ five- and 10-year outlooks.

While leaders in all sectors are significantly more likely than not to express confidence in their institutions’ 10-year outlooks, the degree of their confidence varies. Eighty-five percent of presidents of public doctoral institutions strongly agree that their institution will be financially stable over 10 years—55 percent strongly so. Eighty-seven percent of leaders of private doctoral and master’s institutions express confidence in their 10-year horizon (32 percent strongly).

Presidents of public master’s and baccalaureate institutions—the many regional public universities that aren’t flagships or land-grants—are least upbeat, with only 17 percent “strongly” expressing confidence in their situation over a decade. About three in 10 community college leaders answered that way.

A majority of all presidents, 55 percent, agreed that their institution is “more financially stable now than it was in 2019,” before the COVID-19 pandemic shut their campuses and drove enrollments down by about a million students nationally over two years. Nearly a third, 31 percent, disagreed with that statement.

Two-thirds of presidents (68 percent) who said their institutions were better off now than in 2019 cited increased revenue from nontuition “sources such as charitable giving, government support or auxiliary enterprises” as the primary reason why—almost certainly reflecting the tens of billions of dollars of pandemic recovery aid the federal government poured into college coffers in 2020 and 2021. Slightly more than half (55 percent) said they had either decreased their operating deficit or increased their operating surplus, presumably through a mix of spending cuts as well as revenue increases.

The roughly one-third of campus leaders who said their college was less financially stable now than in 2019 cited a double whammy of decreased net tuition revenue (73 percent) and the impact of the external economy: 72 percent identified increased salary and benefits expenses, given the hot job market of the last two years, and 67 percent blamed higher purchasing costs tied to inflation.

Nearly six in 10 presidents (58 percent) said they expected their institution to be more financially stable next year than it is now, while only 22 percent said they expect their institution to be less financially stable a year from now. Presidents of private nonprofit institutions (69 percent) were significantly likelier than their public college peers (51 percent) to say that, with community college leaders also equally divided: 38 percent said their college was better off now, while 43 percent expect it to be in better financial shape next year.

Presidents who expect to be stronger a year from now attribute that almost entirely to an anticipated rise in enrollment (or at least in tuition revenue), while a third say they also expect to cut their budget in response to economic conditions. A full three-quarters of presidents of regional public institutions (78 percent) say they expect enrollment to be higher.

The 22 percent of presidents who think their situations will be less favorable in 2024 expect labor costs to rise (75 percent) and inflationary pressures to persist (71 percent). Half also expect their enrollment to be lower (54 percent), and 44 percent expect state support to either decline or remain flat.

The role of enrollment in the presidents’ expectations about their financial futures reflects the growing reality that higher education is in an era of haves and have-nots. About seven in 10 presidents of private nonprofit colleges who expect their institution to be better off a year from now expect their net tuition revenue to grow, with presidents in the South and Midwest (60 and 61 percent, respectively) most likely to say that.

Meanwhile, of the one-fifth of presidents who expect their institution to struggle more next year, 68 percent of presidents in the Northeast and 62 percent of those in the Midwest expect enrollment to decline.

While enrollments appear to have stabilized last fall after the sharp drops driven by COVID-19 and the hot job market, they have not begun to rise after nearly a decade of decline, and the recovery to date is attributable in significant part to increased enrollment in certificate programs. Many parts of the country are anticipating declines in the middle of this decade in the number of high school graduates, which would require many institutions to look to older learners or international students to expand their enrollments.

Staisloff of rpk Group said that “while it makes sense that presidents might feel more comfortable as we move further away from the pandemic and its impacts,” many colleges balanced their budgets in the last two fiscal years using the federal stimulus dollars—“funding that has now been completely utilized.” In the next year or two, he said, “those budget holes that were filled by [federal money] are unlikely to be filled by traditional revenue sources like state funding or additional net tuition dollars.”

Mergers and Consolidation

Another indicator of presidents’ relative confidence in their institutions’ financial situations can be found in their answers to a set of questions about whether they are likely to merge or combine academic programs or administrative operations with peer institutions.

Fewer than one in five presidents (18 percent) said that senior administrators at their institution had had “serious internal discussions” in the last year about merging with another college, though nearly a third of presidents of private doctoral and master’s universities (31 percent) and 27 percent of presidents in the Northeast responded that way.

More than a quarter of presidents (28 percent) said they’d had serious internal discussions about consolidating some of their institution’s programs or operations with another college.

One in 10 presidents said their institution was either very or somewhat likely to merge into or be acquired by another college in the next five years, with 17 percent of leaders of private doctoral/master’s institutions and of colleges in the Northeast saying that. Eighteen percent of presidents said their college or university was likely to acquire another institution in the next five years, with leaders of private doctoral and master’s institutions again most likely (37 percent).

One last question on that topic asked presidents not what they think would happen, but what they think should happen. More than a quarter of campus leaders, 27 percent, said they thought their institution should consider merging with another institution, with twice as many private college leaders than public college chiefs answering that way (38 versus 19 percent). Inside Higher Ed’s 2022 survey of presidents asked whether respondents thought their institution “should merge” (rather than “should consider merging”) with another, and 13 percent answered that question affirmatively.

“The survey is consistent with what we are seeing,” John Macintosh, a partner at SeaChange Capital Partners, said via email. In 2021, SeaChange, with ECMC, launched the Transformational Partnerships Fund in 2021 to support colleges and universities in exploring partnerships to improve how they operate and serve students. “Many more institutions want to ‘acquire’ than ‘be acquired.’ Most institutions that want to acquire a peer won’t; most that think they are somewhat likely to be acquired won’t be.”

Do Colleges Need to Change?

If presidents by and large think their institutions are in stable financial condition for the next decade, does that make them disinclined to believe they need to make fundamental changes in how they operate?

Campus leaders seem of two minds on that.

When they were asked questions along those lines most directly, they by and large expressed a recognition that their institutions need to change.

Nearly three-quarters of presidents agreed (30 percent strongly, 42 percent somewhat) with the statement “I believe my institution needs to make fundamental changes in its business models, programming or other operations.” Community college leaders (78 percent, 30 percent strongly) and those from private doctoral and master’s universities (77 percent, 38 percent strongly) were most inclined to answer that way, while only half of leaders of public doctoral universities agreed with that statement, and only 6 percent did strongly.

Similarly, a full three-quarters (76 percent) of presidents agreed (27 percent strongly) that “the pandemic, and subsequent necessary changes (e.g., adopting more remote learning) has created an opportunity for my institution to make other institutional changes we have been needing to make anyway.” Presidents of public master’s and baccalaureate institutions—regional publics—were significantly less likely their peers to agree with that statement (63 percent, and only 19 percent strongly).

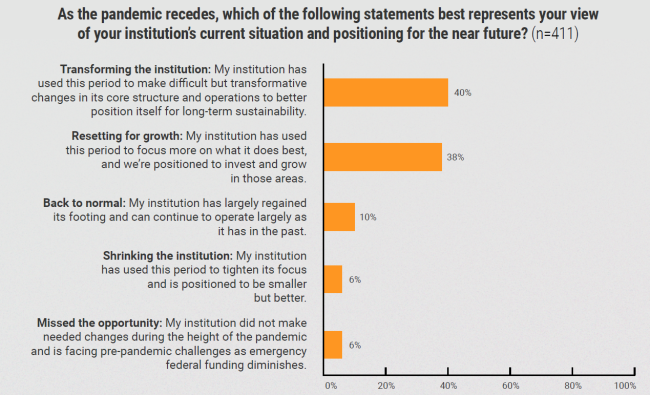

And when asked which statement best represents their view of their institution’s current and near-future positioning, more presidents chose “transforming” their institution (using the period to make “difficult but transformative” changes to better position itself for long-term sustainability) than any other answer.

Half of leaders at public doctoral universities (53 percent) and community colleges (50 percent) answered that way, compared to just 32 percent of leaders at regional public colleges and 25 percent at private baccalaureate institutions. More than one in 10 leaders of private four-year colleges (12 percent) said they had “missed an opportunity” to make needed changes.

Other answers, however, suggest that presidents are feeling less compulsion as the pandemic recedes to make significant changes to their business models or operations.

Fifty-one percent of all presidents still strongly agree that their institution was “pushed to think out of the box during the pandemic in a way that will benefit the institution in the long run,” 45 percent strongly agree that their institution “was able to implement some positive, long-lasting institutional changes during the pandemic,” and 37 percent strongly agree that their college will “keep some of the COVID-19–related changes even after the pandemic ends.”

But all those were down sharply from Inside Higher Ed’s survey a year ago, when 58 percent, 52 percent and 44 percent agreed strongly with those statements.

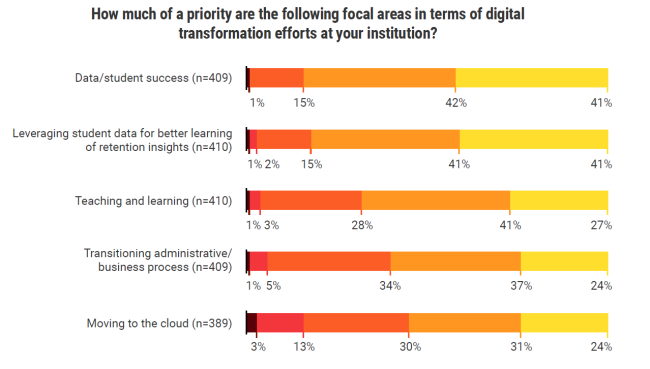

And four in 10 presidents said that “digital transformation” was an essential (13 percent) or “high priority” (30 percent) for leaders at their institution, with 34 percent of presidents from private baccalaureate colleges answering that way.

John O’Brien, the president of Educause, higher education’s technology association, said that while the proportion of presidents focused on digital transformation might seem low, “less than half is a dramatic increase in awareness and support for digital transformation,” he said.

O’Brien said a 2018 survey by the American Council on Education had found just 12 percent of presidents viewed information technology as an important area of strategic development. “Having almost half of presidents a few years later say that digital transformation is a high priority is nothing short of a tectonic shift,” he said.

He also noted that while presidents may be “ambivalent” about prioritizing digital transformation, they are overwhelmingly focused on what he called “most of the most important aspects of digital transformation … When asked about the core components of Dx—student success, data for retention, and enhanced teaching and learning—between 68-83 percent say they are an essential or high priority.”

Presidents’ opinions about the theoretical topic of “digital transformation” aside, their responses to the survey reflect continued ambivalence about the educational and workplace changes that have been steadily unfolding on their campuses.

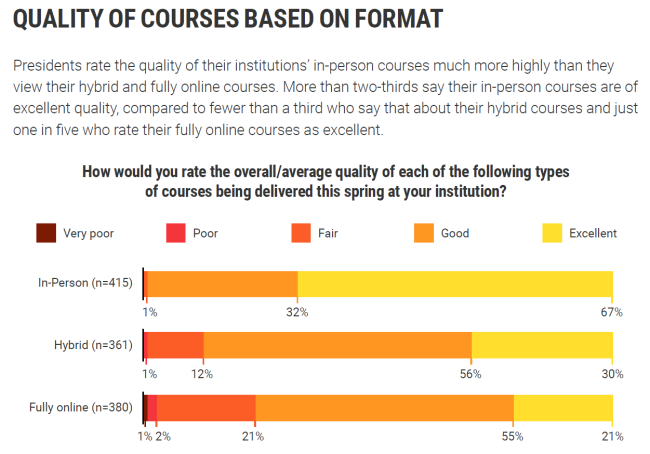

Respondents report that the proportion of in-person courses at their institutions has declined from before the pandemic, from nearly eight in 10 (78 percent) to just over two-thirds (68 percent). The proportions of online and hybrid courses have both increased somewhat.

Asked to rate the quality of those courses, presidents take a much more favorable view of their in-person courses than their technology-enabled ones, as seen below. Compared to a year ago, the divide is closing a bit: last year 73 percent of presidents rated their in-person courses as excellent and 27 percent said the same about their hybrid courses—a 46-percentage-point gap versus this year’s 37 percentage points.

Dale Whittaker, former president of the University of Central Florida and now a senior adviser to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, said via email that he saw presidents’ biases reflected in their answers to this question. First, they are “digital learning non-natives,” and students are likely to hold a different view. Second, leaders on many traditional campuses have an incentive to promote in-person learning because they derive so much auxiliary revenue from housing, dining and parking.

Favoring in-person over virtual forms of learning isn’t just a theoretical matter, he said. “This attitude/belief creates inequities in population-level degree attainment, especially with regard to those who cannot leave their communities, jobs or families to get a degree face-to-face.”

Colleges also seem to be slowly reducing the proportion of employees who work remotely, in line with trends elsewhere in the workforce.

In last year’s survey, 19 percent of presidents said at least a quarter of their nonfaculty staff were working remotely; that number is down to 13 percent this year.

And fully half of presidents said the proportion of those employees who are working remotely this year is either significantly (35 percent) or slightly (18 percent) smaller than the proportion who did so in 2021–22, with just 14 percent saying the percentage had increased.

With remote learning and work in mind, about one in five presidents said their institution was either very likely (7 percent) or somewhat likely (14 percent) to shrink the size of its physical campus in the next five years. Fifty percent said it was “not likely at all” to do so.

Student and Employee Mental Health and Well-Being

Mental health—especially of undergraduates—continues to occupy the minds and agendas of presidents.

More than two-thirds say they are “very aware” of the state of their students’ mental health, holding stable from last year’s survey. In contrast, significantly fewer say they are very aware of the mental health condition of their faculty (46 percent versus 55 percent in 2022), staff (48 percent versus 57 percent) and graduate students (29 percent versus 40 percent).

Two-thirds of campus leaders agree (24 percent strongly, 44 percent somewhat) that their institution has “sufficient capacity” to meet students’ mental health needs. Significantly fewer say the same about graduate students (55 percent) and faculty (46 percent) and staff members (47 percent).

Roughly two-thirds of presidents who said their institution had sufficient capacity to meet students’ or employees’ mental health needs cited increased staffing for on-campus counseling services, increased budgets for mental health-related services, investments in telehealth services and expanded availability of mental health services as the reasons why.

Nance Roy, chief clinical officer at the JED Foundation, a nonprofit that focuses on the emotional health of teens and young adults, said she found it “disappointing” that campus leaders seemed to believe that pouring more of their resources into expanding the number and availability of therapists was the best answer to addressing undergraduate mental health.

“They really need to take a more comprehensive public health approach,” Roy said, focusing not just on direct treatment but to the range of interventions and services that identify students who are struggling and build “connectedness” and resilience.

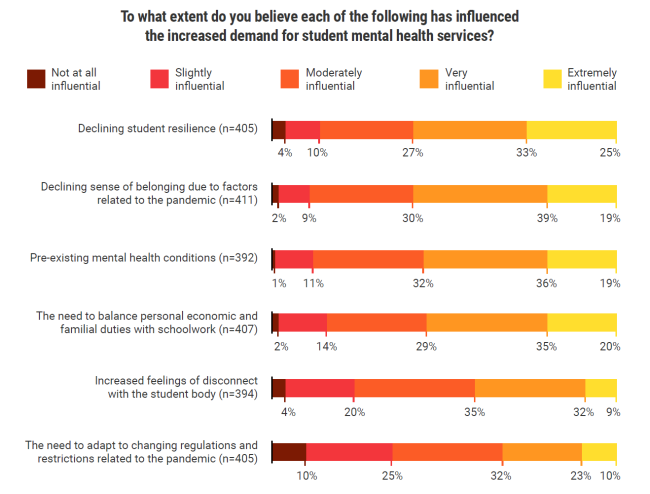

That’s especially true, Roy said, given how presidents answered the last mental health question in the IHE survey, which asked leaders what factors were most responsible for the increased student demand for mental health services.

Their answers—declining student resilience and decreased sense of belonging stemming from the pandemic—suggest that presidents are focused on the wrong solutions, Roy said.

“You don’t need to go to therapy to get resilience or to build an increased sense of belonging,” she said. “There are so many auxiliary interventions that can help with that, from a coach, an academic adviser, residence life.”

“Why are you throwing all your money over there if you this is where you think the problem is?” she added.

Roy also said she thought presidents may be underplaying the importance of taking good care of what she called the “forgotten grad student population.”

“When I think about this from a president’s point of view, they invest a fair amount of money in graduate students, and if they don’t make it through, it’s a big loss for the institution,” Roy said. “Not only that, but they’re the next workforce, and people aren’t a dime a dozen wanting to come to your college to work these days.”

Other Findings

Inside Higher Ed’s Survey of College and University Presidents explored several other themes.

Employee turnover. Despite significant news coverage and campus conversation in the last few years about employee burnout and churn, presidents seem unperturbed about the turnover rate for faculty and staff members at their institution, with twice as many (43 percent) saying they are not worried (13 percent) or slightly worried than very or extremely worried (20 percent).

That may be at least partially explained by the reasons they cite for why employees are leaving: the top reason they identify, by far, is competitive offers elsewhere (86 percent), followed by natural career progression (55 percent). Burnout (52 percent) and lack of opportunity for growth (45 percent) are next, with issues such as lack of work-life balance (27 percent), negative experiences with workplace culture (12 percent) or negative views of leadership (4 percent) trailing.

McClure of UNC Wilmington, who has written widely about the higher education workplace, said the responses “confirm some suspicions and observations I have had, which is that it’s easy for leaders to look outward” to identify reasons why they may be losing employees.

“Attributing most turnover to someone getting a competitive offer elsewhere is a way of deflecting institutional responsibility” for employees’ decisions to leave, McClure said. “That’s as opposed to asking what was it about the organization or institution itself that wasn’t able to offer career progression.”

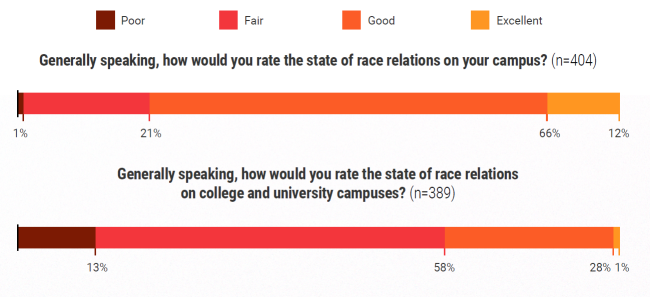

Race relations and affirmative action. Perhaps the most eyebrow-raising set of answers each year in Inside Higher Ed’s survey of campus chief executives are those given when presidents are asked to rate the state of race relations on their own campuses and generally within higher education. They largely speak for themselves:

Related, we asked presidents this year about the potential impact on their institutions if the U.S. Supreme Court, as widely expected, prohibits or restricts the consideration of race and other factors in college admissions. On balance the presidents are sanguine: fewer than one in seven agrees that their institution would have to significantly adjust its admissions or financial policies, would face increased racial unrest or protests, or would see worsening race relations.

While those numbers are slightly higher for presidents at the public doctoral universities and private nonprofit colleges that are likeliest to have selective admissions processes, even those leaders seem relatively unconcerned, with fewer than a quarter of private baccalaureate presidents envisioning problems for their campuses.

Higher education’s image. Survey respondents concede some of the critiques politicians and the public make about higher education but challenge others. More presidents agree than disagree (59 percent to 33 percent) that “public doubts about the affordability of higher education are justified,” with community college leaders (68 percent) much more likely than their peers to agree. In contrast, more disagree (53 percent) than agree (39 percent) that the public is justified in doubting how well institutions are preparing graduates for the workforce and questioning the value of higher education (65 percent to 30 percent).

On politics, the presidents are split: 44 percent agree that “the perception of colleges as places that are intolerant of conservative views is accurate,” while 41 percent disagree. As with the race question, the presidents are more confident in their own institution’s approach: 65 percent agree that classrooms on their campus are “as welcoming to conservative students as they are to liberal students,” while under a quarter (23 percent) disagree.

One on thing there is near unanimity: 77 percent of college presidents agree that the perception of colleges as intolerant of conservative views is hurting public attitudes about higher education.

Student debt cancellation. Presidents are not huge fans of President Biden’s contested plan to forgive student debt. While nearly half of respondents to the survey said they thought the administration’s proposed actions would forgive “the right amount” of debt, the rest were more than twice as likely to say it should not have forgiven any debt (37 percent) than to say it should have forgiven more debt (16 percent). And campus leaders are far likelier to disagree (59 percent) than to agree (21 percent) that student debt cancellation “would make college more affordable.”

Losing the faculty? Inside Higher Ed’s 2022 survey of presidents documented a notable uptick (to 57 percent, the highest in a decade) in the proportion of campus leaders who agreed that faculty members on their campuses “understand the challenges confronting my institution and our need to adapt.” This year that number came back to earth, dropping to 47 percent. That almost certainly reflects the increased tension evident on many campuses as budgets tighten and cuts are considered.