You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

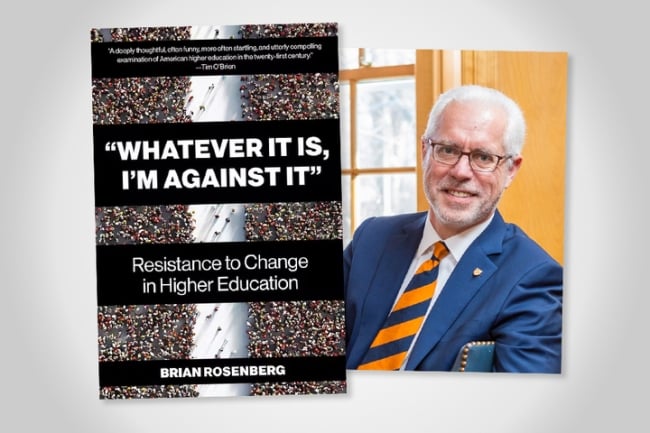

Rosenberg blends memoir, humor and analysis in his incisive examination of higher ed’s resistance to change.

Photos courtesy of Brian Rosenberg | Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed

In his new book, “Whatever It Is, I’m Against It”: Resistance to Change in Higher Education (Harvard Education Press), Brian Rosenberg, president emeritus of Macalester College, distills a career’s worth of experiences and observations into a trenchant critique of the industry he both loves and laments. He argues that the institutions designed to foster critical inquiry and the open exchange of ideas are themselves staunchly resistant to both. The very structures that have become the hallmarks of postsecondary education in America—classroom lectures, shared governance, faculty tenure—are in fact key obstacles to what he calls “transformational” change.

Rosenberg, currently a visiting professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and senior adviser to the African Leadership University, spoke with Inside Higher Ed via Zoom. Excerpts of the conversation follow, edited for space and clarity.

Q: Why does higher ed require transformational change right now?

A: The current financial trajectory of higher education is just not sustainable. For a long time, I resisted that idea … but I’ve come around to the belief that there’s going to be a major disruption of the current market and the status quo, driven first of all by economics. The discount rate at private colleges has been going up about 3 percent a year for an extended period. It’s now over 56 percent. And you can’t just keep cutting the price unless you figure out a way also to reduce the cost of actually providing the service. You keep adding 3 percent a year to the discount rate and eventually you get to 100 percent and you’re giving it away for free.

Then demographics are not working in favor of American higher education. In the second half of this decade, the number of high school graduates is going to decline by about 15 percent. And the market is going to have to rightsize itself. There are unfortunately just too many colleges for that size market.

We’re also seeing—and this is probably the least expected thing—a lower percentage of students from many states choosing to go to college. You have lots of states now in which fewer than half the students are electing to go to college. So you combine the cost of providing it and the willingness and ability of people to pay and the demographics and you have what people have been describing for a long time—not always accurately, but I think it’s true now: an unsustainable economic situation.

Q: At the same time, there’s less of a need for a college education in some fields; we’re seeing more and more job descriptions eliminate the bachelor’s degree as a requirement.

A: Absolutely. You are seeing some states and companies beginning to say, “We’re more interested in your skill set than in your degree.” And that’s related to another reason why there’s enormous pressure: the level of public confidence in higher education has probably never been lower. There are a lot of reasons for that—many of them political and many unfair. But as I say in the book, Republicans send their kids to college, too, and if they’re losing faith in college in a lot of states, that is a majority of the market.

There are also reasons for loss of faith that are not necessarily political. You’re talking about an industry that has a six-year completion rate of … what, 60 percent? And for underrepresented students, under 50 percent. That’s not a very efficient or effective industry. I find it hard to imagine defending the status quo when essentially half your students are not completing.

The public is looking at higher education’s resistance to any kind of serious introspection or internal reform and saying, “You know, you guys aren’t fixing yourselves. And so we’re maybe not going to be quite as confident in you as we used to be.” And the fact that the 18- to 24-year-old generation has the least faith, that’s a real problem. That’s your market. So I’ve just come around to believing that it is both the right thing and probably the necessary thing to change in ways beyond the incremental.

Q: As you note, your book does more to define the problem than recommend solutions. Where would you start if you could trigger transformative change? What is the low-hanging fruit?

A: One is the calendar; the notion that a college degree has to occupy four years with long breaks in the summer and often in the winter increases cost, opportunity costs and time to completion. It is not the case across the globe that a bachelor’s degree has to take four years. It is a remarkably inefficient calendar. I really do think that if some colleges were willing to say to the market, “We’re going to let you get this degree, and it’s going to only take you three years—three years of paying tuition, and three years out of your life”—that could get some traction.

The other would be some serious thinking about pedagogy and how students learn. Because the research is there if people were willing to take it seriously and think about ways of providing an education that is not quite as reliant upon lots of faculty with Ph.D.s. Is that easy to do? No, but it is something that I think there should at least begin to be some serious discussions about.

Q: You write a fair bit about the rise of non-tenure-track faculty. How do they shape an institution’s relationship to change?

A: We’re not going back to a system where the percentage of tenured faculty goes up. I actually believe if non-tenure-track faculty were given more say in the way colleges are run, it would help change, because they’re the ones who are benefiting least from the current model.

You could take the current system, where non-tenure-track faculty are, in many places, just gig workers, and give them more job security. You can be non–tenure track and still have a multiyear contract with a reasonable salary and access to benefits and also participate in the governance of the institution—and the decision-making in your department, which in many cases doesn’t happen now. They could be a powerfully transformational force if they were actually given a little more agency.

And I would say the same of graduate students … They know the system is broken. They know they’re training for jobs that don’t exist. They have all kinds of ideas about how to change the way they’re being trained and educated and change the way that we think about universities. But again, they have no say.

Q: Your book is very funny in places, reminiscent of higher ed satirists like David Lodge and Julie Schumacher. What role do you see humor playing in your analysis?

A: Most important, there’s a role for humility. This book obviously is, in many ways, critical of higher education. But what I did not want to suggest is that I was somehow looking down on or claiming to be better than a lot of the people participating in the current system. As I say in the book, I feel like I am guilty of a lot of the things that I point to … There’s a tendency in these discussions to treat everything with high seriousness. I think humor breaks that down, makes the narrative a little bit more engaging. And as long as you’re not doing it in a cruel way and also poking some fun of yourself, I think it perhaps helps get your message across more effectively.

Q: The book is as much memoir as anything, full of candid reflections on your own career, including your 17 years as president of Macalester. What, if any, regrets do you have?

A: At every stage of my career, I feel like if I could go back and do it again with what I know now, I would be different. I look back on myself as a young assistant professor and realize that I was one of those faculty members who would criticize the administration without having the slightest idea what I was talking about. I was just fortunate to have senior leaders who were willing to overlook that and see the potential in me, and I’ll always be grateful for that. Do I wish as a president, I had pushed harder on certain things? Yes. But I’m also realistic about what I probably could have accomplished. If I had pushed certain things really hard, a) I’m not sure they would have happened and b) I might have just had a shorter presidency.

Q: You describe shared governance as a big drag on the movement for change—a kind of anchor weighing institutions down.

A: Shared governance is a system designed, in my view, to make sure that any changes are very slow and very incremental. Anytime you work toward consensus within a large, heterogeneous group, you’re going to probably end up taking a lot of time—and with an outcome that is the least objectionable to the most people, which is antithetical to anything revolutionary or transformational … So if your goal is to avoid the worst, then shared governance isn’t necessarily bad. If your goal is to accomplish the best, then I don’t think shared governance is typically a very effective way to get there.

Shared governance is one of those things that if you ask any college president off the record, they’ll probably express their frustration, then they’ll go back to their campus and wax poetic about the wonders of shared governance, because that’s what they have to do to survive.

Q: Would faculty and trustees look at it the same way?

A: My guess is that trustees would share a lot of my views on shared governance. A lot of them come from industries, for better or worse, where decision-making is made by a smaller group; it’s more top-down and more rapid. And I think there are some faculty who would get it. Certainly there are some faculty who are frustrated by the inability of their own body to make necessary changes. But it is still kind of an article of faith that unless there is shared governance, the administration is just going to run roughshod over higher education and turn it into a giant corporate enterprise.

Q: At the beginning of the tenure section, you talk about how much you dreaded writing that chapter. Why was it so difficult?

A: First of all, I do not want in any way to align myself with some of the political attacks on tenure that are coming from red state legislators and governors. I think the reasons that they are going after tenure are completely wrong and the alternatives they suggest would be worse. I don’t think the response to concerns about tenure is to have decisions made by governors and legislatures.

I spent so much of my life defending tenure. I had tenure. And, you know, I’ve finally come around to believe that while it has its strengths, it is one of the things that is impeding the necessary change in the academy. So at a certain level, it felt like a betrayal of my own history.

It’s not like I enjoyed saying, “Tenure could be a problem." But I was determined to try to be as honest and constructive as I could possibly be. And so I wasn’t going to shy away from the things that people don’t want to talk about.

Q: In the last chapter, you talk about how your involvement with the African Leadership University allowed you to reflect on the strengths and weaknesses of American higher education. Where’d you net out?

A: The founder of ALU went to Macalester and Stanford; the current head went to Princeton. So these are people who are by birth African, but they know the U.S. higher education system inside and out.

The American system, even if you believe it’s the best system in the world, just won’t work in Africa; it’s too costly. And there aren’t enough Ph.D.s. So they had to immediately say, “What system will work, and not just be functional, but maybe be better than the system that I was educated in?” That’s why you see a different calendar—a three-year calendar with shorter breaks. It’s why you don’t see the fragmentation of the curriculum into 35 different majors. It’s why you see much more experiential learning.

These are all things that they were able to do because they didn’t have the history, the restrictions, the angry alumni that American universities have to deal with. They had to figure out how to set up a process of change that brings in multiple viewpoints but can move quickly. It’s a combination of the start-up mentality that you find in entrepreneurs and some of the thinking in higher education to try to create this new institution in this new environment. I feel reinvigorated by it.