You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

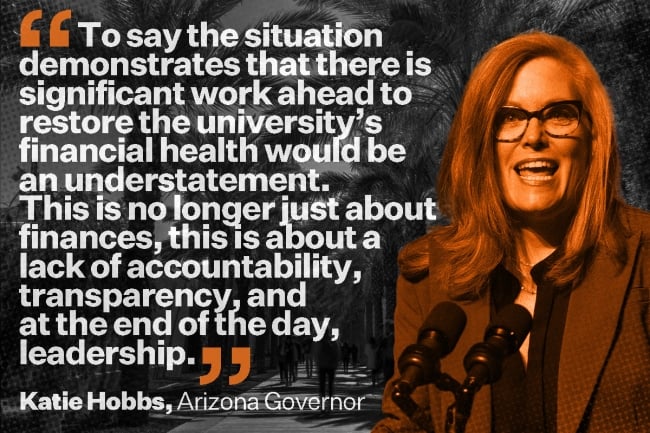

Arizona governor Katie Hobbs has demanded more transparency from the Board of Regents and a series of reports on how UA fell into a financial crisis.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Getty Images | Arizona, Office of the Governor

After the University of Arizona miscalculated the amount of cash it had on hand by millions of dollars—an error that was revealed in November—a plan for financial recovery is slowly beginning to take shape.

Officials presented a rough outline of that plan to the university community Monday, following a special meeting last week of the Arizona Board of Regents and a scathing letter from Democratic governor Katie Hobbs, who said the financial crisis showed a “lack of accountability, transparency, and … leadership.” She demanded a series of reports on the matter.

At a leadership forum Monday, UA president Robert Robbins and ABOR executive director John Arnold—who is also serving as the university’s interim chief financial officer, much to Hobbs’s disapproval—presented both the financial problems and potential solutions, offering a look at the long-term plan to ease a projected $177 million budget deficit.

Accountability and Action

Robbins opened the campus forum by owning up to his part in the crisis.

“First of all, I think you all know we have some serious financial issues. And I want you to know that I take full responsibility for that. It happened while I was here. And I also take full responsibility for helping lead and chart a pathway forward for us to get to better financial health of the university,” Robbins said, adding that the challenge will require universitywide solutions.

The university has already instituted a hiring and compensation freeze, and officials explained Monday that more changes are on the horizon—including some that will be sweeping in scope. While Arnold said UA is not in “imminent danger,” he added, “Our spending patterns are dangerous.”

At the core of the problem is a flawed budget model and overspending on strategic initiatives, he said.

Arnold explained that the university has employed three different budget models over the past decade, noting that the lack of a unified structure led to overall spending problems. He said 61 of 81 units at UA are in a deficit and that “excessive discounting” on tuition “led to a flattening of our revenue model.” He also cited factors such as inflation and costs related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Challenges for the athletics department, which has come under fire for its slow repayment of a $55 million loan from the university, have also contributed to UA’s financial woes. Arnold noted upheaval across college athletics, pointing to the disruption of sports revenues, which he attributed to a model “that has been flipped on its head.” He added that flawed financial projections on a national level have left many other university athletic departments with operating deficits as well.

“All of these factors conspired together to produce widespread deficit spending across campus,” Arnold said. “This is not an athletics problem” or “a problem in the president’s office.”

In offering up solutions, Arnold made a handful of promises about what UA wouldn’t do: it wouldn’t reduce need-based aid for in-state students, cut need- or merit-based aid for current or accepted students, enact furloughs, or reduce employee retirement benefits.

At the same time, UA revealed a series of corrective measures it is adopting, beginning with athletics: “We’re going to reset their budget,” Arnold said, and “install hard caps on spending” while also seeking to grow athletics revenue.

Arnold pushed back on notions that the purchase of the embattled for-profit Ashford University, which has been renamed the University of Arizona Global Campus, created financial issues. Officials have repeatedly denied that Ashford’s $256 million price tag exacerbated UA’s problems. On Monday, Arnold said the projected loss from UAGC stood at $2.4 million for fiscal year 2024, though he anticipates a positive cash flow of $3.1 million in fiscal 2025.

Cuts are also coming. But specific details have not yet been revealed.

At Monday’s forum, Arnold noted that certain departments will be centralized by early March: business and finance, facilities management, human resources, information technology, marketing and communications, and the university advancement office. He also said that UA will seek to reduce administrative costs by reviewing positions across leadership, including “every single vice presidential position,” among others, “to see if we need those positions moving forward.”

University leaders assume there will be a 5 percent budget reduction for fiscal year 2025 and have asked each unit to present a plan reflecting operations if its budget is cut by 5, 10 or 15 percent. Administrators will then decide on funding levels for individual units. Indeed, officials will be required to make a series of decisions over the next two months as they draft UA’s fiscal 2025 budget.

The university also plans to introduce a new budget model by Jan. 1.

Arnold added that UA has tapped third-party accounting and consulting firms to help ease the process of restructuring the athletics department and increasing efficiency at UAGC.

Enduring Doubts

Some UA employees have expressed skepticism about the administration’s plan to get the university’s finances back on track, calling for Robbins to resign and threatening a no-confidence vote.

In the end, Robbins made a plea for patience, telling community members, “Now that we’ve got the diagnosis,” it will take everyone working together “to execute the right treatment plan.”

Leila Hudson, a professor in the School of Middle Eastern and North African Studies and chair of the Faculty Senate, said that after the forum, faculty members expressed concern that “the athletic debt to the academic side of the house is going to be passively accepted and absorbed,” which is unacceptable. She added that faculty members are also worried about the role of the Huron Group, which has been engaged as a third-party consultant, because Huron offers “exactly the kind of outsourced corporate consulting, even with its so-called specialty in higher education, that got us into this problem in the first place.”

(Huron Group did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.)

In some ways, the crisis has driven a “noticeable uptick in shared governance,” Hudson said, with faculty offering “meaningful contributions to the larger financial plan.” But many employees still resent cost-saving measures “being imposed on the academic units, which are not, by and large, anywhere near the main source of the problems.”

Hobbs did not respond to a request from Inside Higher Ed for comment about Monday’s forum. But she made clear in a letter to the Arizona Board of Regents that she expects greater transparency and accountability from the board—which she sits on as an ex officio member—and detailed reports about strategies and tactics to resolve the financial issues. Hobbs also called for “a clear distinction between governance and operations of the university and ABOR.” She singled out Arnold as interim CFO, likening him to a “fox guarding the henhouse” in her letter. Hobbs also asked for a report about the rationale and process for the Ashford purchase.

In an interview with Inside Higher Ed Tuesday, Arnold explained that the interim CFO role fell to him at the request of both UA and ABOR officials. He cited his past experience as state budget director under former governor Janet Brewer before he joined the Board of Regents.

Arnold will transition out of the CFO role “as quickly as is reasonable,” he said, but he did not provide a timeline. He added that he hopes to “provide some consistent leadership in this area.”

He also noted that the governor made “excellent points” in her sharply worded letter.

“Some of the information the university put out—really from June forward—was incorrect. And it’s taken us a while to get our hands around the nature and depth of the problem,” Arnold said. “And I completely understand why the governor, the public and the on-campus community [have] been frustrated by those inaccuracies and those delays.”

The emphasis now, he said, is on transparency, accuracy and rebuilding trust as the university seeks solutions.

But for Hudson and other faculty members, the lack of trust in leadership is palpable.

“This has been incredibly destabilizing and emotional for our campus,” Hudson said. “Feelings are running extremely high, and they’ve spilled out into the wider community of southern Arizona. So everyone is weighing in. And the number of requests that I get … asking for a vote of no confidence is skyrocketing. It’s off the charts.”

But she pointed to vacancies in senior positions, noting that she’s “not in a hurry to create more of a vacuum at the top” while the university works to solve its pressing financial issues.

“I would rather keep trying to find solutions for the immediate time being,” Hudson said.