You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

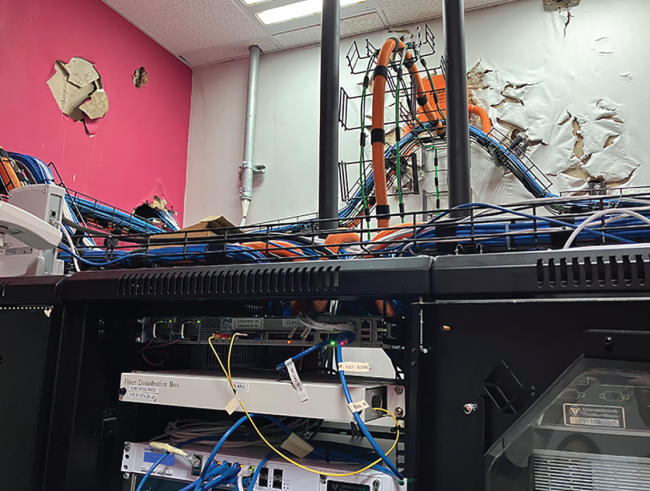

The report detailed needs for repairs at Hispanic-serving institutions and showed images of buildings at HSIs in Puerto Rico damaged by Hurricane Maria, including this server room.

U.S. Government Accountability Office

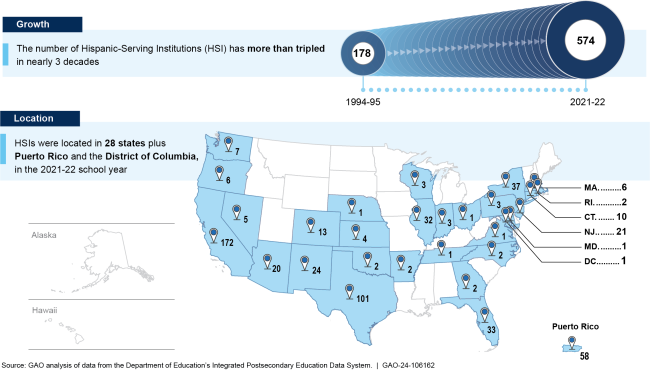

Hispanic-serving institutions (HSIs), colleges where at least 25 percent of undergraduates are Hispanic, wrestle with severe infrastructure needs, including expensive backlogs of delayed repairs to campus buildings, according to a new report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO).

HSI advocates say the findings support what they’ve known for years, that the institutions are underfunded and need more financial support.

The report, requested by Congress and released on Tuesday, drew on survey responses from 169 colleges across the U.S. from May to June 2023. GAO researchers also visited campuses in California, New Mexico, Texas and Puerto Rico and interviewed U.S. Department of Education officials, facilities experts and experts on HSIs, alongside a review of relevant data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, or IPEDS.

“What you see overall is a picture of schools struggling with extensive facility and digital infrastructure needs, and trying to figure out how to cover those, and not being fully satisfied with the funding that’s available for them,” said Melissa Emrey-Arras, director of education, workforce and income security at the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

The report found that the estimated average deferred-maintenance backlog for HSIs was about $95.2 million. HSIs spent $4.6 million on these types of projects on average in the most recent year, a fraction of what was needed. And an estimated 77 percent of HSIs had planned or recently completed a deferred-maintenance project related to health or safety, most commonly accessibility problems or electrical or fire hazards. More than half of HSIs, 54 percent, expected their backlogs to grow in the next three years. And an estimated 56 percent of HSIs predicted a need for more space on campus in the next five years.

On average, an estimated 43 percent of HSI building space needed some type of repairs or replacement. Meanwhile, 14 percent of HSIs had more severe needs, with at least 75 percent of their building space in need of repairs. That need may be partly driven by the fact that 65 percent of HSIs had weathered at least one natural disaster in the past five years that damaged campus facilities or required renovations. The report notes that the problem is bound to get worse, as most HSIs are concentrated in areas expected to experience severe weather due to climate change, according to the U.S. Global Change Research Program.

Emrey-Arras stressed that these institutions need updated facilities to serve current students, attract prospective students and bring in the tuition dollars needed to continue to upkeep campuses.

“They’re trying to make sure they can remain attractive to students,” she said. “Students don’t want to see a dormitory that looks like it should be demolished as part of their come-to-the-school tour.”

U.S. Government Accountability Office

‘The Forgotten Higher Education Community’

Antonio Flores, president and CEO of the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities, said he’s visited many HSI campuses and seen some of the disrepair, so he expected the report’s findings were “going to be bad—but not this bad.”

He noted that these institutions serve at least 5 million students, and that two-thirds of Latinos attending college are enrolled at HSIs. He also pointed out that the U.S. Department of Labor projected that Latinos would make up 78 percent of new workers nationwide between 2020 and 2030.

“You’re talking about the future workforce of the nation that is not getting quality education …” he said. “That really is what’s at stake … This is not just about HSIs and Hispanics. It’s about the nation’s well-being.”

He believes HSIs don’t get enough funding from the federal government or philanthropists in part because “we’re the newest kid on the block.” A federal designation for HSIs didn’t exist until 1992 and they didn’t receive any special appropriations until 1995. His association has only existed since 1986 so there hasn’t been an “advocacy structure” for these institutions in place for that long.

He also believes the federal government and donors have neglected HSIs.

“We are basically the forgotten higher education community …” he said. Philanthropic organizations “are not really paying enough attention to our institutions because they keep going back to the same cohort of institutions they have worked with forever and forget the rest.”

This is not just about HSIs and Hispanics. It’s about the nation’s well-being.”

-Antonio Flores, Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities

Many colleges that are now HSIs were also underfunded before an HSI designation even existed, said Anne-Marie Núñez, executive director of the Diana Natalicio Institute for Hispanic Student Success at the University of Texas at El Paso.

She noted that most of the colleges and universities eventually labeled HSIs were regional institutions and community colleges serving high numbers of students of color, not the flagships, which tend to be more selective, charge higher tuition rates and secure sizable endowments and more federal grants. And while some better resourced institutions, such as the University of Arizona or the University of California, Irvine, have achieved HSI status in recent years because of demographic shifts, they’re not the majority.

Historically, “there is an element of racialization of these institutions,” she said.

Núñez highlighted a 1987 lawsuit against the University of Texas system which accused the system of underfunding institutions in areas with large Mexican-American populations compared to its other universities, among other concerns. Historically Black colleges and their advocates have filed similar lawsuits against states for unequal investments in their institutions.

A Digital Divide

In addition to facility problems, these institutions also lack up-to-date digital infrastructure, the report found. About a quarter of HSIs reported having internet speeds that didn’t meet their needs, and 22 percent didn’t have internet that could extend to outdoor areas of campus, the survey found. Meanwhile, at about a third of HSIs, at least 10 percent of students had difficulty accessing the internet off-campus because they didn’t have the right devices or couldn’t afford internet at home, making on-campus internet especially important. Most HSIs, an estimated 74 percent, have also undergone cybersecurity attacks in the past five years, leading to increased investments in cybersecurity.

Offering hybrid courses has proved difficult as well. Of HSIs that offer these options, 90 percent report hitting up against at least one technological or financial challenge to continuing them. A lack of IT personnel was a problem for 69 percent of those institutions.

The report also explored the sources of funding available to HSIs for capital projects over the last five years. While 43 percent of HSIs overall suggested they were satisfied with their funding, an estimated 74 percent of public HSIs reported insufficient state funding hampered their ability to undertake infrastructure projects. Three-quarters of private HSIs indicated declining tuition revenues were a struggle. The U.S. Department of Education has three grant programs available to HSIs, though department officials reported that institutions usually use those funds for student services and other costs rather than infrastructure repairs or improvements.

There is an element of racialization of these institutions."

-Anne-Marie Núñez, Diana Natalicio Institute for Hispanic Student Success

Azuri L. Gonzalez, executive director of the Alliance of Hispanic Serving Research Universities, said there’s been a “compounding” of student needs, made especially apparent during the pandemic, that’s led to increased costs.

“Usually, these institutions will require additional kinds of support systems in terms of management of financial aid or management of wraparound services,” she said, because they’re serving high numbers of first-generation and low-income students. Federal COVID-19 dollars helped colleges provide these supports, and the technology needed for online and hybrid courses, but as those funds dry up, many HSIs are “not able to sustain it.”

Deborah Santiago, CEO and co-founder of Excelencia in Education, an organization dedicated to Latino student success, said, in the absence of endowments or excess funds, these institutions find themselves having to choose between spending on student support services and infrastructure costs. Often academic supports win out.

“Every student deserves to be educated in a facility that is of a quality that they feel they can get a good education and that they feel valued, because they’re going into a space that supports their needs,” she said. Student support services and physical and digital infrastructure “go hand in hand.”

Flores believes the findings in the GAO report will help organizations like his lobby Congress that HSIs need a funding program dedicated to capital improvements at their institutions. (HBCUs have had a capital financing program dedicated to that purpose since 1994.)

This report is “telling us and telling Congress and the public at large that we just need to invest in a more serious way in institutions that represent the very future of the country,” especially amidst an “increasingly sophisticated labor force” in which graduates “need more and more higher education of the highest quality possible,” he said.

Andrés Castro Samayoa, associate professor of higher education at Boston College, said the report not only details HSIs’ current infrastructure needs but shows how those needs are only going to increase in the future as climate change progresses, cybersecurity attacks on higher ed institutions increase and digital infrastructure becomes all the more important.

These findings make the case that more targeted financial support for these institutions “isn’t really optional but necessary,” he said.