You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

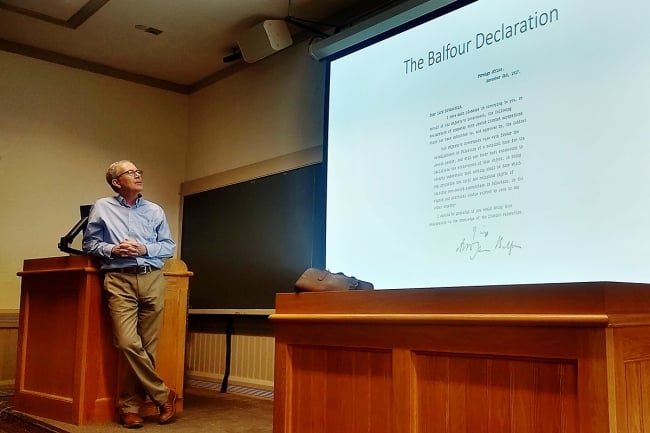

Derek Penslar, pictured here leading a class on modern Jewish history, also regularly teaches a Harvard course on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Derek Penslar

When Hamas’s Oct. 7 attack on Israel catalyzed a contentious protest movement on college campuses across the country, Michelle Murray, an associate professor of political studies at Bard College in New York, and her colleagues wondered if there was a role they could play in promoting thoughtful discussion of the conflict on their campus.

“I was observing students, on the one hand, being really hungry for knowledge and, on the other hand, kind of encountering a lot of terminology that’s circulating around in the discourse,” she said.

Those observations, combined with extensive discussions with her fellow faculty members, led Murray and another professor to develop a course for the spring semester designed to give students tools to talk about the conflict in Gaza by focusing on key terminology. In the course, titled Keywords for Our Times: Understanding Israel and Palestine, students will explore how words like “Zionism,” “genocide” and “settler colonialism” have been defined and applied by different groups of people.

Murray said she was only able to pull off the new offering so quickly because Bard expedited the approval timeline for the course, which involves the collaboration of many other colleagues who plan to guest lecture.

But Bard is not the only institution hoping to foster understanding by examining the conflict through an academic lens. Ever since protests over the Israel-Hamas war arose on college campuses, proponents of open dialogue have called on universities to use their cornerstone resource—education—to tamp down tensions. Protesters’ vitriol, the argument goes, comes at least in part from a lack of knowledge of others’ perspectives.

“College campuses should be a place for protest and disagreement and free speech—and they should be a place where students can learn about complex subjects and have safe spaces for respectful dialogue with those they disagree with,” wrote The Boston Globe’s editorial board, lauding Dartmouth University for hosting forums on the history of the region in the weeks following the attack.

The appetite is clearly there. Many professors who teach courses on the conflict report that their spring semester classes have seen all-time high demand, filling quickly and boasting substantial wait lists. While few of these classes are new offerings—as they can take several semesters to develop—existing courses are being updated with new information about the current conflict, increased historical context and lessons on how to parse information about the war from different sources.

Smadar Ben-Natan, an Israeli lawyer turned academic who is teaching an undergraduate course and a graduate seminar on the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict at the University of Washington this spring, said that her courses, which focus on exploring multiple perspectives, will be able to meet “the moment that we’re at and … answer some of the difficult questions about colonization, self-determination, resistance, violence, state violence that this moment brings up.” (The undergraduate course is full, with 45 students registered and more on the wait list.)

The courses were previously taught by another professor, but Ben-Natan is updating them in light of the ongoing war. She plans to add an exercise at the end of each class in the graduate seminar that asks students to reflect on how the conflict impacts their lives on and off campus.

“I think it’s important, because many times students feel that they’re alone and they don’t have safe spaces to question things that they hear and think in a setting that is both safe and also informed and nuanced and, in a way, confidential,” she said. “I want to reflect that we are all, in a way, facing new realities and having to reconsider: How do we position ourselves? How do we connect with demonstrations, rallies, all kinds of political movement that is happening?”

Passionate Participants?

Professors aren’t sure what kind of impact their courses will have on campus climate, though. Derek J. Penslar, the William Lee Frost Professor of Jewish History at Harvard University, will be a teaching a class on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict next fall. Tensions run especially high at Harvard, which has made headlines both for pro-Palestinian student protests and the administration’s response; university president Claudine Gay resigned Jan. 2 following widespread condemnation of her performance at last month’s congressional hearing on antisemitism and mounting allegations of plagiarism.

The course—which Penslar has taught at least 15 times and describes as “an overview of the history of Israel and of the Palestinians viewed through the lenses of Middle Eastern history, Jewish history and global historical movements such as nationalism and colonialism”—has never attracted the students who are most impassioned about the issue, he said.

“The students who walk in my door are not necessarily the same ones as those who are in Harvard Yard screaming,” he said. “More often than not, my students are curious, intelligent, and they usually do have a political view at one point or another. But they’re open-minded or else they wouldn’t bother taking my class."

Paul Scham, a professor in the University of Maryland’s Israel Studies department who teaches an introductory course about the conflict every fall, has had the same experience in his classes. Even when the war between Israel and Hamas began in the middle of last semester, he said, few students shared their own opinions on the matter.

Adam, a pro-Palestinian student organizer at the University of Maryland who declined to share his surname out of fear of being doxed or blacklisted, is not planning to take any courses related to the conflict. He isn’t worried about professors being biased, he said. But having grown up learning about the Palestinian territories, he believes he is already “very well accustomed to the narratives and counternarratives” surrounding the conflict, he said, and he did not want to have to argue with other students about “who deserves what rights.”

Pro-Palestinian protesters “stay away from dialogues that seek to paint the two sides as equal because … [we] see this relationship as a colonized/colonizer relationship,” he said. “It’s not two equal sides beefing it out.”

Learning to Disagree

Still, some professors wish students were more willing to voice opinions—even unpopular ones—in their courses.

For next year, Scham added a couple of sentences to his course description, saying, “‘We of course will talk about the war, and bring your opinions; all opinions are welcome,’” he said. “Because I have been disappointed, for the 14 or 15 years I’ve taught this course, that comparatively few people in the course seem to really be involved or passionate. I thought I would have to keep people from each other’s throats, and at least in Maryland … everyone seems really respectful of others’ feelings. That’s good, obviously, but I’d love to hear some passion.”

Penslar plans to take a similar step: he is considering making it a course requirement to disagree with him on at least three occasions during the semester so that students learn to feel more comfortable and confident with respectful discordance.

Paul Kohlbry, a postdoctoral associate at Cornell University who teaches a class called Palestine and the Palestinians, believes that taking an academic approach to the conflict can actually increase tensions. For students enraged about an injustice, “learning more will probably make you more upset,” he said. “It would be strange if the more you learned, the less tension, antagonism and conflict there was.” But he believes that tension can be good thing, raising the stakes and awareness of important issues.

Kohlbry’s course, which focuses more on the culture of the Palestinian people than on politics, has attracted students who are curious but uninformed about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as well as impassioned activists—which makes it hard to tailor the lessons to all levels of interest, he said.

The first time he taught the class, last spring, the conversations weren’t particularly contentious. “Most of the students were Muslim students or Palestinian students who wanted to take the class to learn more about who they were and where they were from,” he said.

But this spring, things might be different; Kohlbry, who plans to reorganize the course slightly to deepen understanding of the current war, believes student anger about Cornell administrators' response to the Oct. 7 attack and subsequent protests will make its way into the classroom.

Whether or not the biggest activists sign up for courses on the conflict, both Penslar and Murray said they hope the lessons they teach will spread to others on campus through word of mouth. Both their courses are lower level, meaning they are open to almost all students. They are also larger-than-average courses for their respective campuses; 40 students are enrolled in Murray’s course, despite Bard typically capping class sizes at 22.

Especially at a small college—Bard enrolls 1,800 undergraduates at its main campus—one impactful class can go a long way.

“One of our goals with this course is to foster richer dialogue within the community at Bard,” Murray said. “That’s what my hope would be, even as these students who are already really committed and passionate don’t take the course, that there’ll be ripple effects.”