You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

College graduates report more civil engagement, dinners with family and awareness of the environment, according to Gallup data.

iStock/Getty Images

Would people be more likely to go to college if they knew it wouldn’t just improve their job prospects and future salaries but would make them healthier, more charitable and more neighborly?

According to a new report by the Lumina Foundation and Gallup, the benefits of higher education go far beyond employment and earnings; a postsecondary degree can improve outcomes in everything from personal health and character to civic engagement and relationships. And the more advanced the degree, the more positive the outcome: for instance, 92 percent of respondents with a graduate degree said they voted in the most recent federal election, compared to 87 percent of those who hold a bachelor’s degree, 79 percent of those with an associate degree and 59 percent of those with no postsecondary education.

In fact, on 49 out of the 52 metrics the study measured, people with postsecondary education expressed a stronger positive connection than those without. (The only metrics that showed no correlation were respecting people who do not share one’s political beliefs and doing more domestic chores. Additionally, a college education was more strongly associated with one negative trait: feeling “discouraged or saddened by things outside my control.”) The report drew largely on data from existing Gallup polls related to attitudes toward work as well as toward social values such as health, civic engagement and philanthropy.

“Looking across multiple variables and all aspects of life, you see overwhelming support that education beyond high school is absolutely worth it. The more education you have, the better life, better job that you’re likely to have,” said Courtney Brown, Lumina’s vice president of impact and planning. “You can't really dispute the data here.”

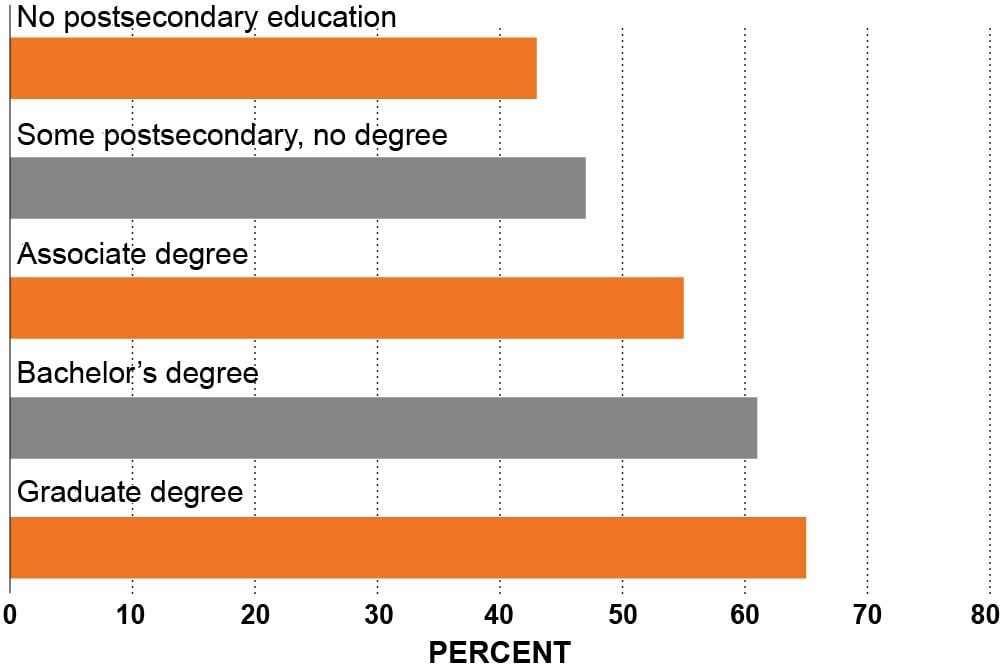

Respondents who rate their current health as excellent or very good

Data by Gallup / Lumina Foundation | Graph by Justin Morrison

Colleges have long tried to prove their worth by showing that, in fact, graduates do fare better financially than those who don't receive a postsecondary education. But despite the data, the general population remains skeptical in the face of a robust job market, rising tuition prices and divisive culture wars that have permeated higher ed. The researchers at Lumina and Gallup hope that by highlighting the other benefits of higher education, they can help attract potential students to college.

According to the report, released today, the metrics that correlate most strongly with higher education are perhaps the most obvious; those who have attended college are much more likely than those who haven’t to perform well on a numeracy, literacy and problem-solving exam, as well as to report that their achievements “required years of preparation.”

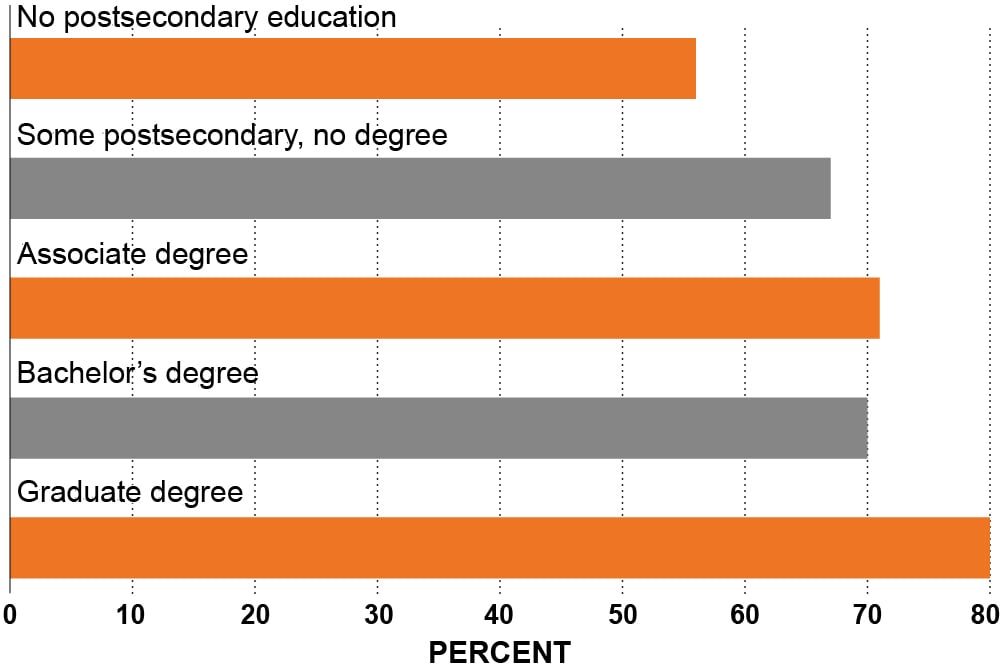

Respondents who strongly, somewhat or slightly agree that people outside of their family often ask for their advice

Data by Gallup/Lumina | Graph by Justin Morrison

But for other metrics, the connection to higher education appears less overt. Individuals who attended an institution of higher education are more likely than those who didn’t to report that they are in good health, that they volunteer, that they “try to minimize harm to the environment” and that people often ask them for their advice.

And some metrics show more variable results; for instance, 59 percent of respondents with a graduate degree said they eat dinner with their family nightly, compared to 57 percent of those with an associate degree, 54 percent of both those with a bachelor’s degree and those with no postsecondary education, and 51 percent of those who went to college but did not graduate.

Correlation or Causation?

Sandy Baum, a senior fellow in the Center on Education Data and Policy at the Urban Institute, noted that the report repeatedly calls such traits “effects” of higher education, though the findings only demonstrate a correlation.

“They seem to be saying almost in all cases that college caused this. There is strong evidence that college does cause a lot of these things, but certainly not all,” she said.

Previous research, she noted, has controlled for factors like wealth when studying whether education leads to better health outcomes, making it easier to establish a causal relationship. But she acknowledged that it would be incredibly difficult to do the same for all 52 metrics.

Brown agreed that some of the metrics seemed more likely to be impacted by outside variables than others; for instance, wealthy people are better able to both attend college and pay for doctor’s visits and health care, she acknowledged, potentially leading to better overall health for the college-educated. But she argued that higher education's positive association with so many different factors indicates that, over all, it is, in fact, beneficial.

Next Steps

The next step is to figure out how to use this data to actually convince people outside the higher education “echo chamber,” as Brown called it, to consider such nonfiscal factors when deciding whether to attend college.

“This isn't going to change overnight. How do you begin to change the narrative on education beyond high school?” she said.

Michelle Van Noy, director of Rutgers University’s Education and Employment Research Center, said the report offers a valuable “counterbalance” to the idea that high earnings should be the main goal of pursuing a college education.

At the same time, she suggested that the metrics presented aren’t as distant from career-readiness skills as one might expect; several of them—including the ability to get along with people from different backgrounds and having the confidence to achieve one’s goals—are crucial for thriving in most workplaces.

“These are what people would call soft skills, cognitive abilities … these tend to be broader capabilities in a person that, I think, are what make education important for career outcomes,” she said. “But it’s harder for people to see that. It’s not as clear as a program that’s very tightly linked to a job.”