You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The report was inspired in part by data from the Eviction Lab showing that families with young children are at high risk of eviction.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | RichVintage/E+/Getty Images

Fewer than one in five student parents who are threatened with eviction while enrolled in a bachelor’s degree go on to finish their program, according to a new study from New America, which highlights eviction as a top predictor of a parent’s ability to earn their degree.

Just 15 percent of student parents who face eviction complete their bachelor’s degree, compared to 38 percent of those who don’t face eviction, the study found. (The report focused on those threatened with eviction, meaning they received an eviction notice, regardless of whether they eventually lost their housing.) Parents seeking associate degrees who were threatened with removal from their homes were somewhat more likely to graduate (26 percent) than those in four-year programs, but they still lagged far behind student parents who hadn’t faced eviction, 51 percent of whom completed their associate degrees.

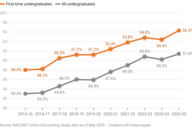

The study relied on millions of Post-Secondary Employment Outcomes records from colleges and universities in six states, eviction court records compiled by the Eviction Lab at Princeton University, and other federal government data. Its findings point to the dramatic impact that a loss of housing can have on student parents, who comprise one in five undergraduates.

“Parenting students face a reality where the immediate need to pay rent and put food on the table takes priority over long-term economic security for their family,” the report states. “We know from research by education economists … that obtaining a postsecondary credential is often the surest path to economic security for American families, but all too often systemic barriers make it hard, or even impossible for parenting students to complete a degree.”

Edward Conroy, senior policy manager on the higher education policy team at New America and one of the study’s authors, said the report was inspired in part by the Eviction Lab’s research showing that families with young children face the highest rates of eviction of any group.

The report also highlights which student parents were most likely to experience eviction. Parents under the age of 24 accounted for 44 percent of evictions; Black parents, too, faced eviction at disproportionate rates, making up 57 percent of student parents threatened with losing their home.

These demographics line up closely with the eviction demographics of the general population, the researchers said.

“I think that’s reflective of broader trends we see in the rental market, which was kind of surprising to me because I thought for a lot of reasons—because of the different housing contexts of students and around college campuses—maybe we’d see something different there,” said Nick Graetz, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Minnesota and one of the report’s researchers. “Maybe there’d be some sort of protective buffering effects built in of different things about being enrolled in college, but we don’t really see that.”

Student parents who are threatened with losing their homes also face worse outcomes after they leave the program, whether by graduating or dropping out; on average, the total family salary of a student parent five years after they were last enrolled is $59,000 if they’ve faced eviction, versus $126,000 for student parents unaffected by an eviction. Most worrying, student parents threatened with eviction also have a much higher mortality rate in the 10 years postenrollment.

“It’s literally life or death that we’re talking about for these students,” said Nicole Lynn Lewis, founder of Generation Hope, a nonprofit that supports student parents. “These are really severe outcomes that all of us need to be paying attention to and taking very seriously.”

Lewis said the report reinforces what she has heard from student parents since Generation Hope’s founding about their struggles securing stable housing and paying their bills, which tend to be higher for parents of young children due to the high cost of childcare. It also resonated with her own experience as a teen mother who started college months after giving birth to her child, she said.

The report suggests several opportunities for institutions and governments to help students avoid losing their homes, including maintaining aid funds that they can tap to help pay rent or other expenses during emergencies. Lewis said that colleges should also build family housing on campus so that student parents have a convenient, stable housing option; currently, she said, only 8 percent of all colleges and universities in the U.S. have housing where students can live with their children.

It’s also important for institutions to be proactive in their support of student parents, Lewis said. At Generation Hope, staff members meet with students at the beginning of the term to try to anticipate whether they might encounter financial challenges later in the semester that could impact their housing.

“There are a lot of assistance programs that don’t start to kick in until an eviction notice is received by a family,” she said. “But for Generation Hope, we’re really intentional about helping students before they’re in that state of crisis … it’s important for us to create policy solutions—institutional policy and also public policy solutions—that are anticipatory, that are preventative, rather than waiting for that housing eviction and for that family to literally have nowhere to go.”