Free Download

College and university presidents are deeply worried that the coronavirus crisis could wreak havoc on their institutions' finances in the near term and, especially, beyond.

But right now, they say they're most concerned about the toll the crisis could take on the mental health of their students and employees.

Those are among the key findings of a survey of 172 campus leaders Inside Higher Ed conducted with Hanover Research last week (March 17-19), as the sweeping scope of the COVID-19 situation began to come into clearer focus in the United States.

About the Survey

"Responding to the COVID-19 Crisis: A Survey of College and University Presidents" is available, free, for download here.

The survey was conducted by Hanover Research on behalf of Inside Higher Ed.

Inside Higher Ed's editors will lead a webcast discussion of the survey's results on Wednesday, April 1, at 2 p.m. Eastern. Please sign up here.

The survey was made possible by advertising support from Cengage Learning, Everspring, Huron, Liaison and Wiley.

The 172 presidents who responded to the survey answered a set of questions about their near-term and longer-term priorities, the actions they had taken thus far in response, and where they felt best equipped (and not) to handle the impact of the crisis. (Four-year public college leaders were underrepresented among the survey's respondents, at 17.4 percent, while they made up 23.6 percent of the invited sample.)

The questions were generally focused on operational strategies rather than long-term thinking about organizational transformation.

Among the findings:

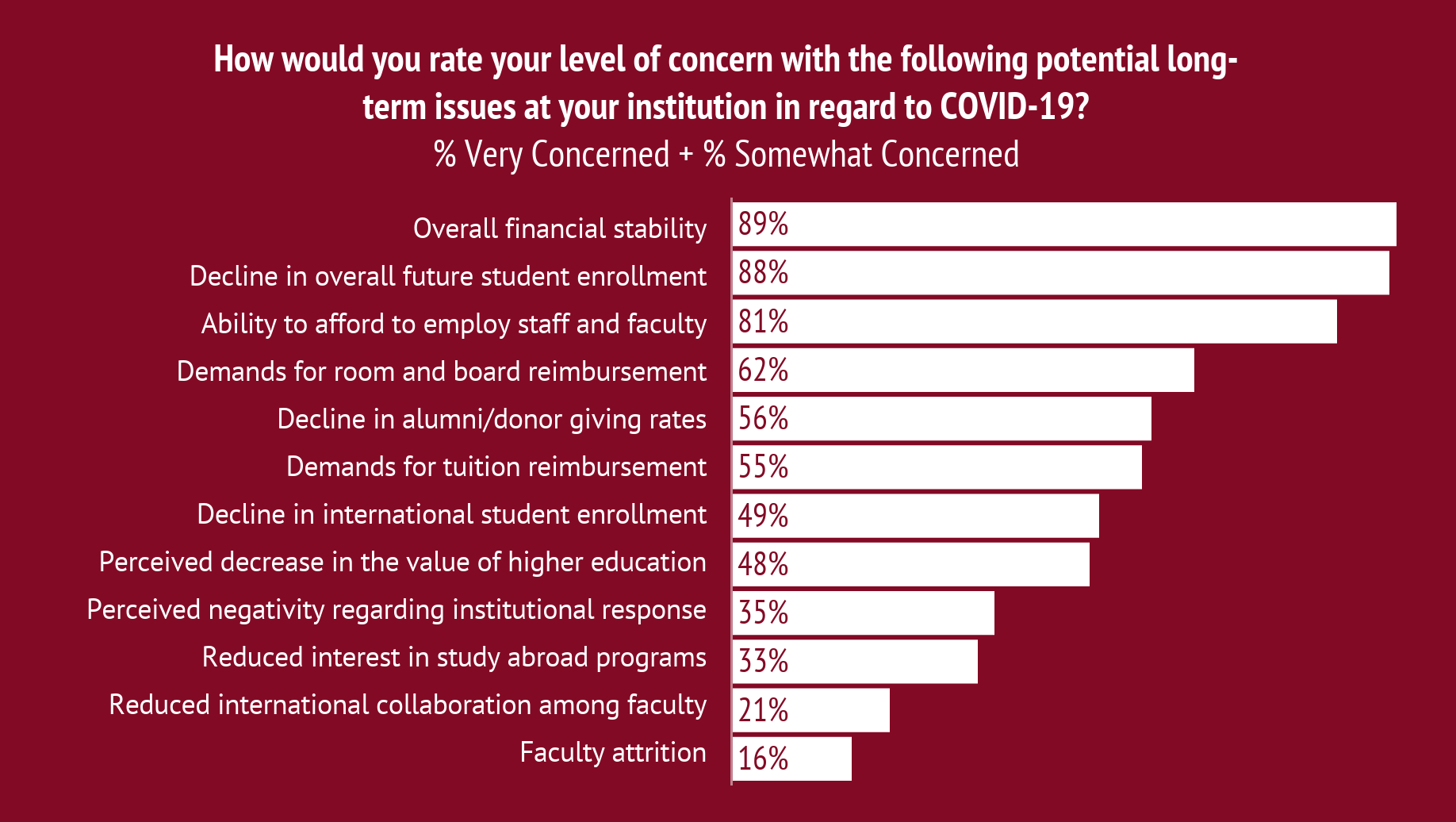

- Presidents put the mental health of students and employees atop their list of short-term concerns -- while their colleges' financial stability and potential enrollment declines are their top longer-term worries.

- While nine in 10 campus leaders say mental health is their top concern, fewer than two in 10 say their institution has invested in more mental or physical health resources in response to COVID-19.

- In the sudden, forced shift to remote learning, presidents' biggest concern is keeping students engaged (81 percent), followed by ensuring they continue to have access to the education (69 percent).

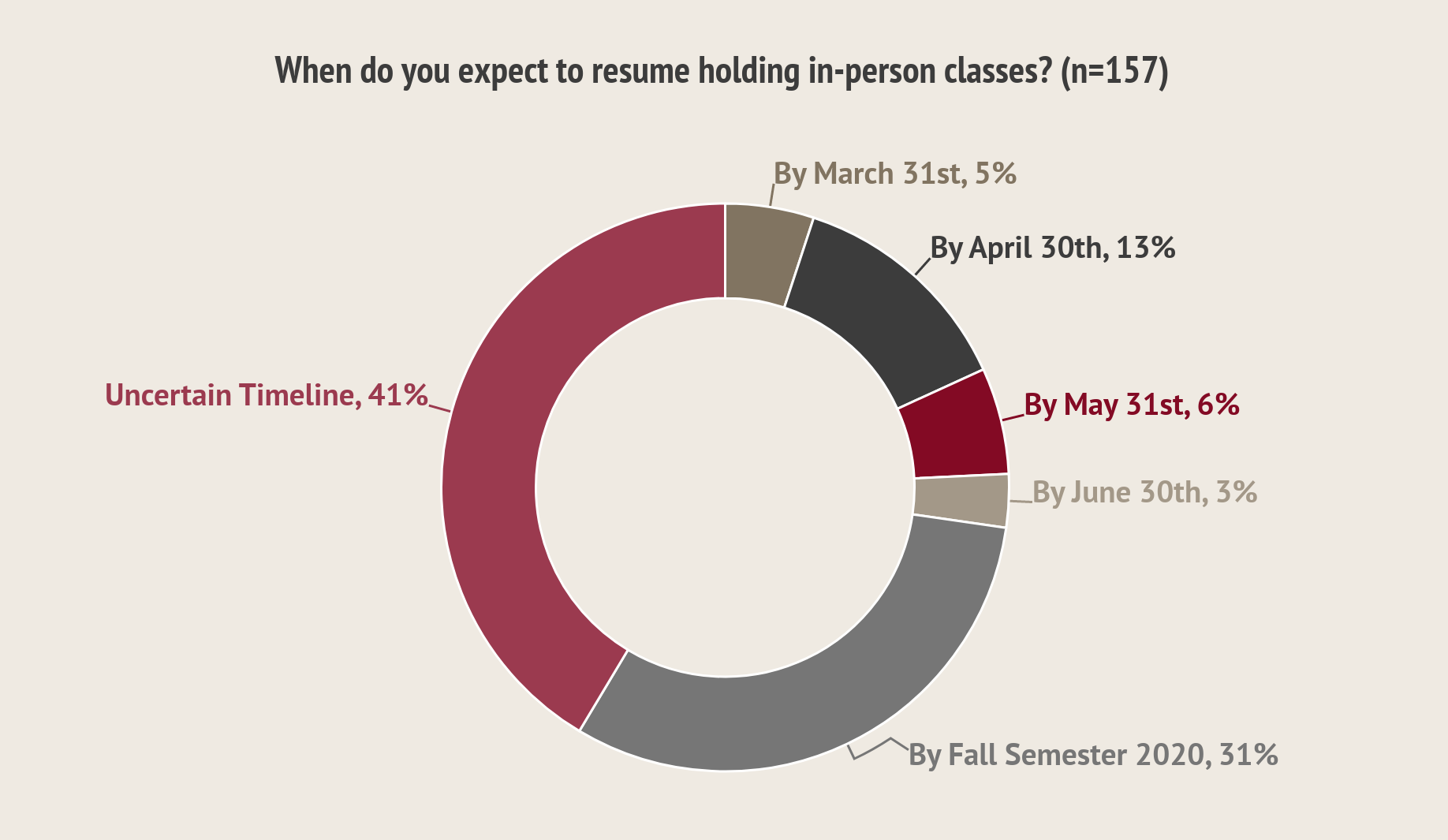

- About a third of presidents foresee in-person classes resuming by the fall semester, but about four in 10 say they can't predict at all.

- Asked where they need the most support from governments or others, presidents overwhelmingly cite federal stimulus funds to make up for losses and help with financial planning.

Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education, said the survey reinforced what the lead association of college presidents is hearing from its members, and showed campus leaders to be focused where Maslow's hierarchy of needs suggests they should be: "on the safety and security of their people, and on their ability to continue their operations."

"The things that lie ahead are ahead -- lots of gathering clouds on the horizon," Mitchell said. "But in the first instance, the students and stakeholder safety is the No. 1 priority of institutions."

The Focus Right Now

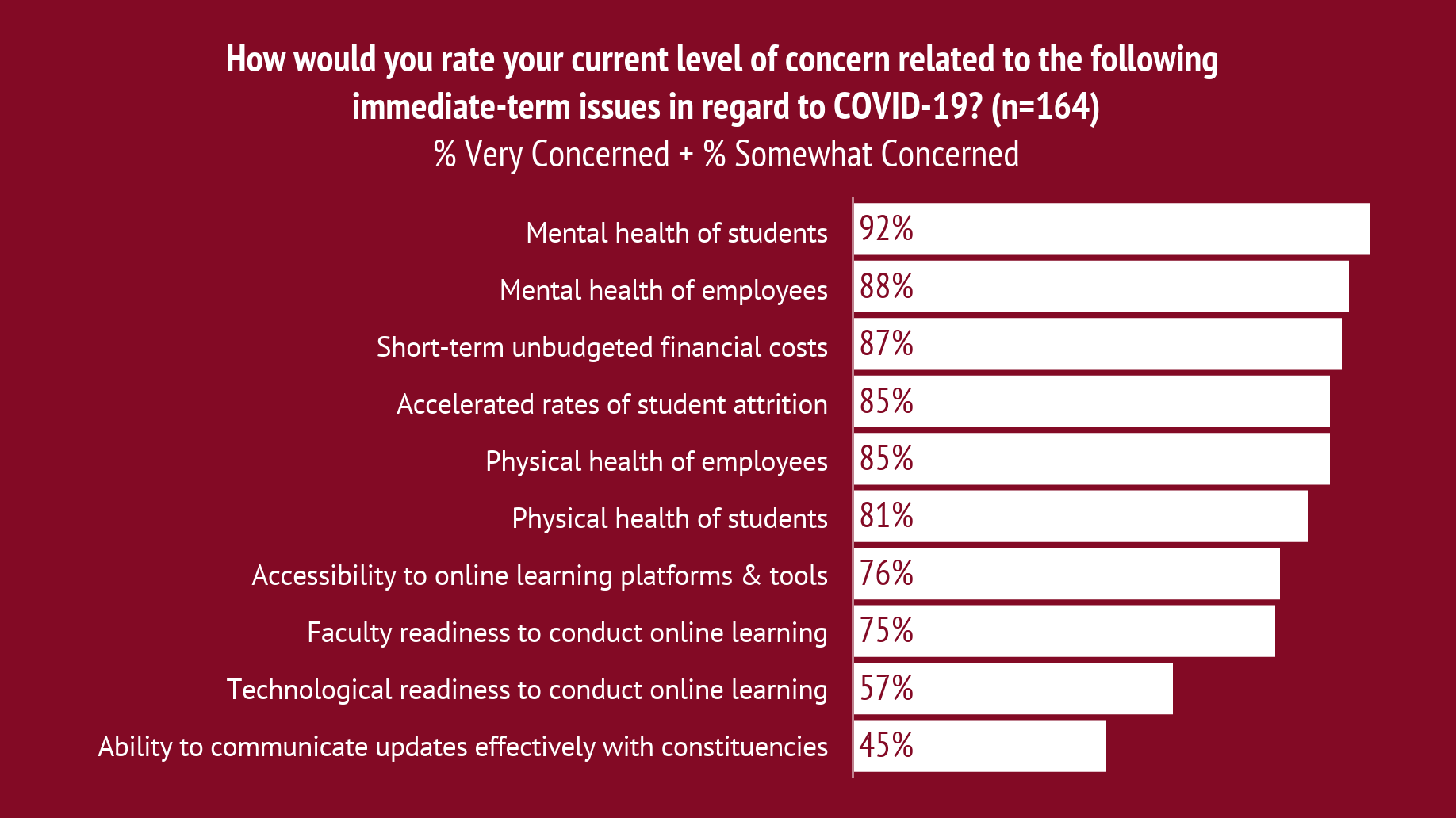

The survey first sought to gauge presidents' views on the burning platform issues -- those that were occupying their time and mindspace right now. Asked to rate their level of concern about 11 "immediate-term" issues, campus leaders appeared to prioritize the health and well-being of their people over what are clearly their anxieties about their institutions' financial security -- though only by a small margin.

The mental health of students topped the list of presidents' short-term concerns, cited by 92 percent of presidents, 37 percent of whom said they were very concerned. The mental health of employees followed next, at 88 percent. Two areas that could hurt institutions' near-term economic condition -- unbudgeted financial costs and accelerated rates of student attrition -- came next, followed by concerns about the physical health of students and employees.

About three-quarters of campus leaders expressed concern about students' ability to gain access to the technology tools and platforms needed to continue their education remotely (76 percent) and their faculties' preparedness to deliver virtual education (75 percent). They worried less (56 percent) about their institutions' technological readiness to deliver remote learning.

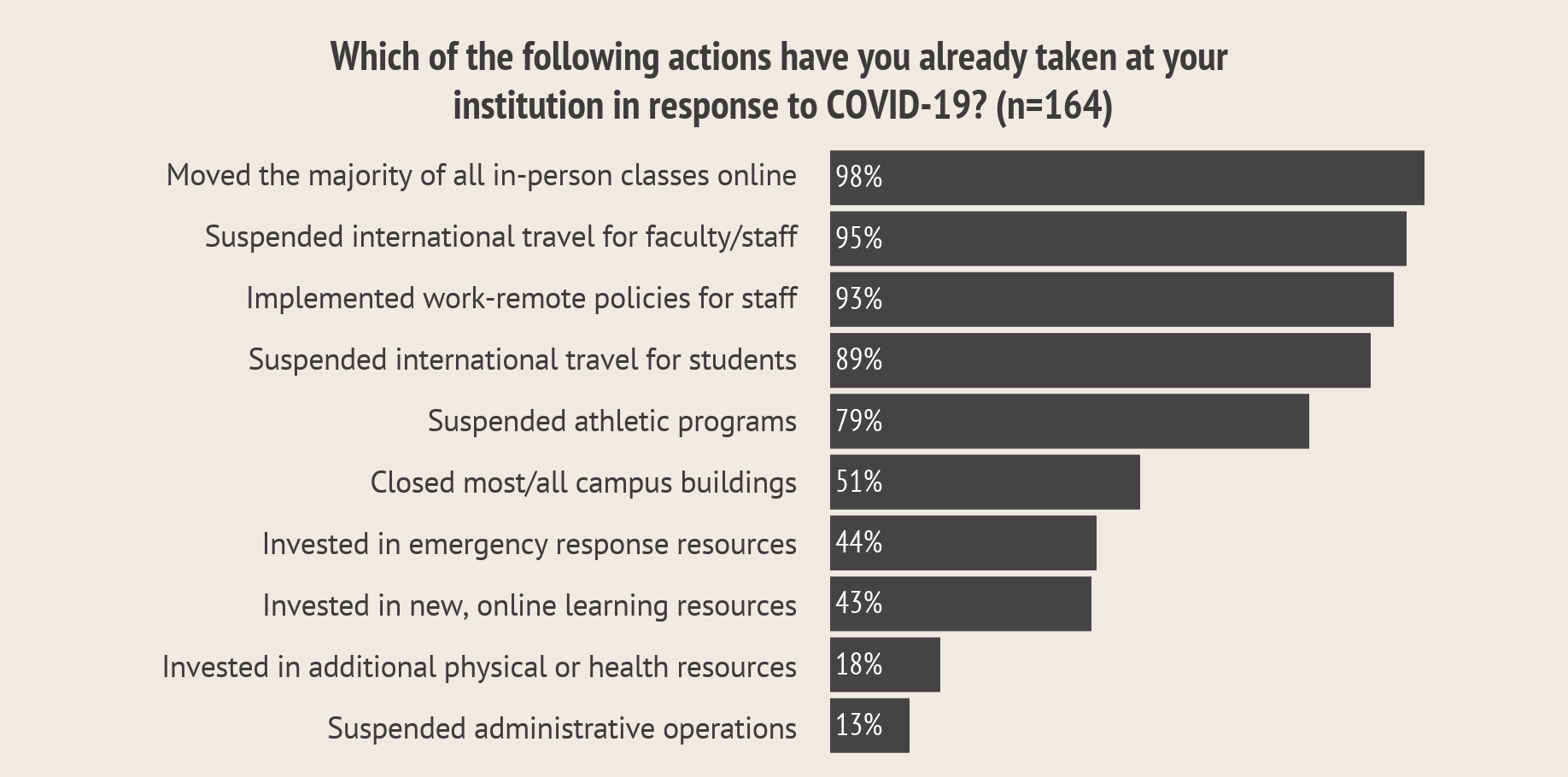

The survey shows possible mismatches between presidents' top concerns and the actions they've taken so far in response. Asked which steps they had taken (as of last week) as the coronavirus impact cascaded on their campuses, their overwhelming focus has been on closing down their campuses and bringing students and employees back from abroad (or barring them from going).

Far fewer, though (43 percent), said they had taken steps to invest in new online learning resources, which may be because they already had the technology to conduct the sort of remote learning most have embraced in the short term, focused on using videoconferencing technology to stream synchronous instruction.

But only 18 percent said they had invested in additional mental or physical health resources, which seems potentially at odds with their concerns about student and faculty mental health. That's especially true given that many colleges acknowledge having inadequate counseling and other resources to deal with mental health issues in the best of times.

That may not change any time soon.

Presidents who had not yet taken the actions outlined above were asked how likely their institutions were to take those same actions in the future. Of the large majority of presidents who said they had not yet invested in additional physical or mental health resources, fewer than half, 44 percent, said they expected to do so down the road.

Chuck Staben, a professor of biological sciences and former president at the University of Idaho, said it "didn't make much sense" to him that presidents were identifying mental health "as the key issue and not investing [in] it." He said he suspected campus leaders "also see this financial problem looming and don't want to invest at a time when they don't know what their finances will be," but added, "You have to invest to address your problems. If you all see this as the big problem, it's surprising you’re not investing."

Mitchell of ACE said he believed many institutions have invested significantly in student mental health pre-coronavirus, in response to growing demand for services. So "as institutions look at where are the holes they need to fill," he said, "happily student mental health is not at the front of the line because of the investments they’ve already made."

But that doesn't mean responding to student mental health concerns will be easy for institutions or presidents, Mitchell said. "Just as it's hard to move classes online, it's even harder to think about how you take all of your student supports and take them online," he said. "Presidents are grappling with taking forms of engagement that have formerly been campus-based and turn[ing] them into services online or at a distance."

Going Virtual in a Hurry

As seen in the chart above, almost every college ended in-person instruction as the coronavirus hit and moved all teaching and learning into remote or virtual settings, typically after pausing instruction over planned or extended spring breaks to help prepare professors and students alike for the transition. In general, Inside Higher Ed's reporting suggests that the process has generally gone smoothly in its early days, with relatively few complaints from students or significant interruptions in delivery.

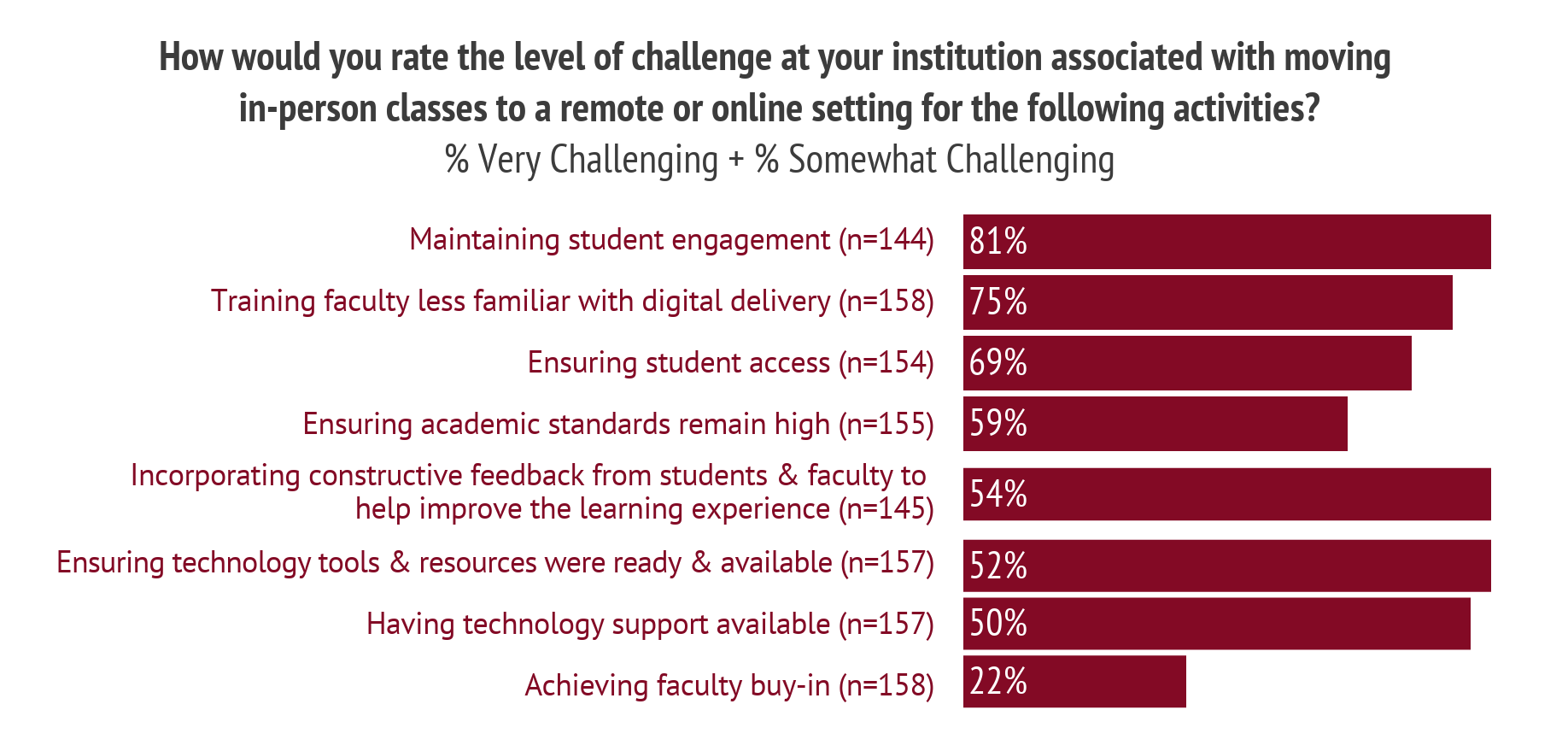

While faculty support for technology-enabled learning is historically very mixed, as Inside Higher Ed's annual surveys of faculty views on technology show, that does not appear to be the case in this situation, with fewer than a quarter of presidents saying they found it challenging to get faculty buy-in for the sudden move to remote learning.

But three-quarters of presidents said they found it either very or somewhat challenging to train instructors who are less familiar with digital delivery. Inside Higher Ed's 2019 Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology found that fewer than half of professors had taught an online course, and on some campuses that figure is likely to be much higher.

The other significant challenges presidents identified around the move to remote learning had to do with students. Slightly more than two-thirds of campus leaders (69 percent) said they viewed ensuring student access as a challenge, but a greater number, 81 percent, expressed concern about maintaining student engagement.

That's probably true, in part, because of the widespread acknowledgment that the brand of remote learning taking place in most classes at most colleges this spring isn't the sort of well-designed, active learning-focused digital courses that advocates for online education champion. They are more likely the best that the small band of hardworking instructional designers that most colleges have could build on the fly with a group of faculty members with greatly varying levels of familiarity and comfort with technology and digital pedagogy.

Those courses will probably get most colleges (and their students) through this spring semester, especially with relaxed grading standards and greater-than-normal understanding on all sides that these are extraordinary times. But come summer, or certainly fall, if campus classrooms are still closed, the pressure will be on institutions to ensure that they've created online courses that keep students engaged and are of high-enough quality to avoid the worries the presidents expressed about student attrition when asked above about their short-term concerns.

About a third of presidents, 31 percent, said they expected to resume in-person classes by the fall, and about one in five predicted before that. But 41 percent said they weren't sure, and the prospects for a quick turnaround have arguably darkened even since the campus leaders were surveyed a week ago.

That question -- will colleges be able to create an online learning experience that satisfies and serves students well if the coronavirus continues to curtail traditional enrollment? -- may at least partially underlie some of the presidents' long-term concerns for their institutions.

Rumblings have been heard in some quarters about student -- and perhaps more so, parent -- dissatisfaction with the idea of paying the same tuition rates that they paid for an immersive, on-campus education when their children are taking classes via Zoom in their childhood bedrooms.

Barely more than half of presidents surveyed, 55 percent, said they're worried about demands for tuition reimbursement, and it's probably true that most reasonable people will understand that most institutions couldn't flip a switch in the middle of this crisis and magically produce an entirely new and high-quality learning experience within days or weeks. But the view might change if that's still the case by fall.

Presidents' most significant long-term concerns related to COVID-19 relate to broader financial and enrollment issues, with 89 percent saying they are concerned (46 percent very much so) about overall financial stability and 88 percent (57 percent very concerned) about declines in overall enrollment.

The enrollment questions are plentiful. Will existing students, once they've spent the spring term learning from their homes, choose to enroll at a college closer to home (and potentially a lower-cost local one) than return to their residential college in another state, especially if the health situation remains unsettled?

Will incoming freshmen be so frozen in their decision making this spring that they postpone enrollment for a year or, again, opt to enroll at a local community college while the situation resolves it? (About half of presidents also express worries about an almost-certain decline in international enrollment.)

The overall financial questions are even more varied. In addition to whatever enrollment hit colleges might take, institutions almost certainly face a wide array of unexpected expenses from the onset of the coronavirus situation, from demands for room and board refunds (which concern 62 percent of presidents, and which numerous institutions are already paying) to increased cleaning bills.

Layer on top of that lost revenues for auxiliary enterprises such as parking and summer facilities rental, and any of a slew of other possible unexpected or additional costs, and the financial picture for many institutions will have worsened -- potentially very dangerous for the 20 to 25 percent of colleges and universities that ratings agencies and others have tended to view as living on a razor's edge.

Help From Elsewhere

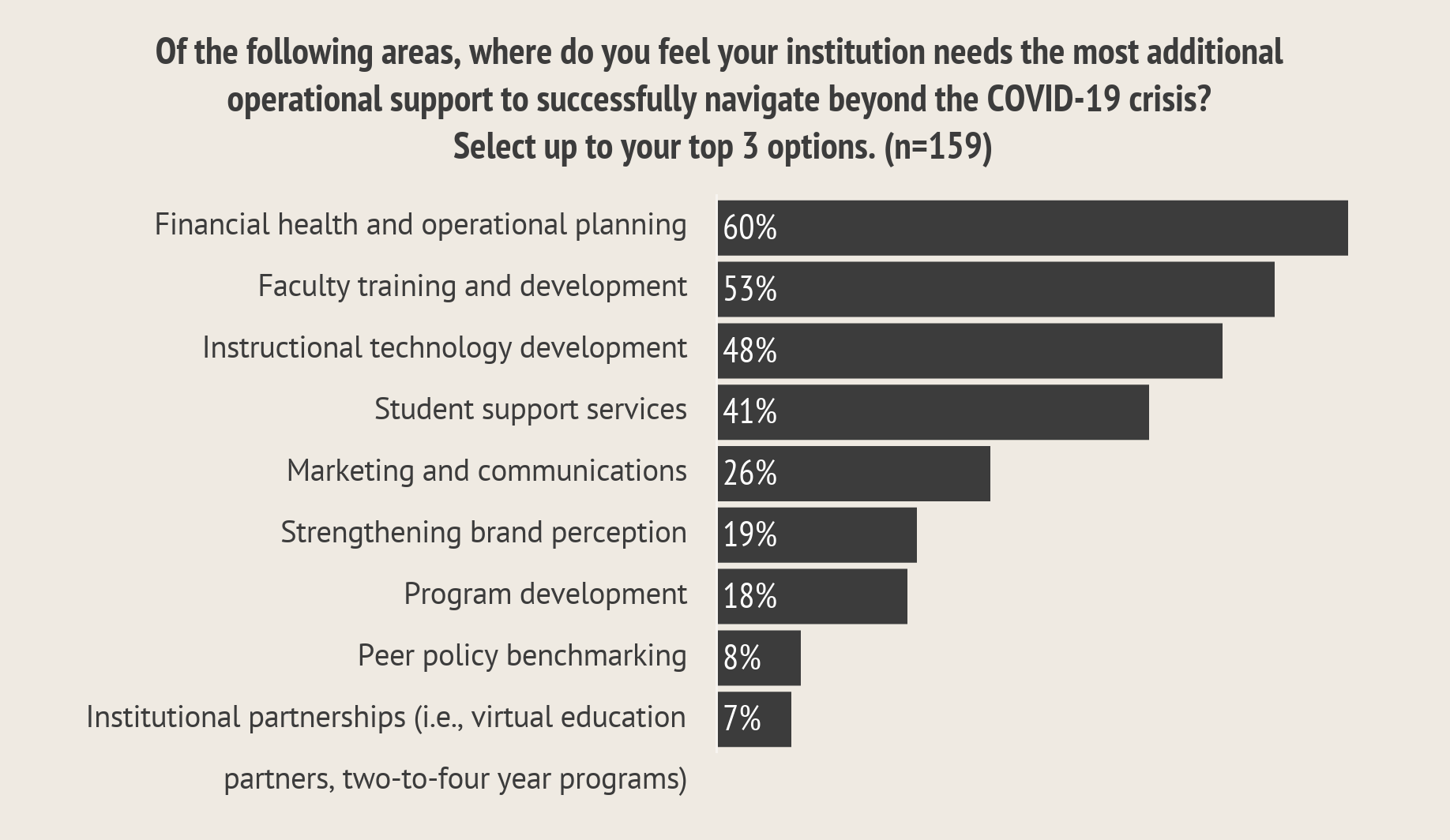

The focus on finances is amplified by presidents' answers to questions about where they most need or would like additional operational or government support to "navigate beyond the COVID-19 crisis."

More presidents cite a desire for financial health and operational planning support (60 percent) than for anything else, followed by help with faculty training and development (53 percent), and instructional technology development (48 percent).

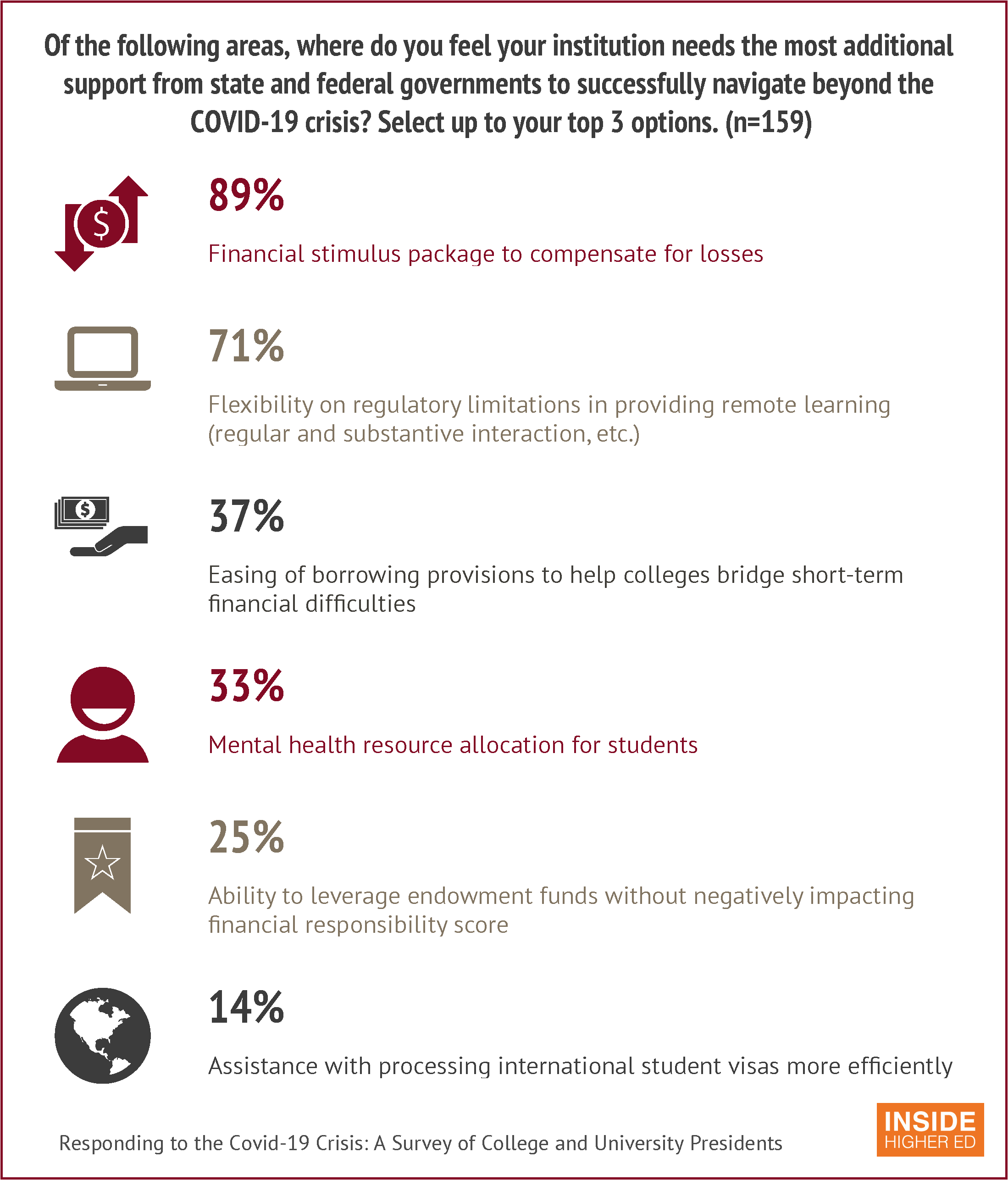

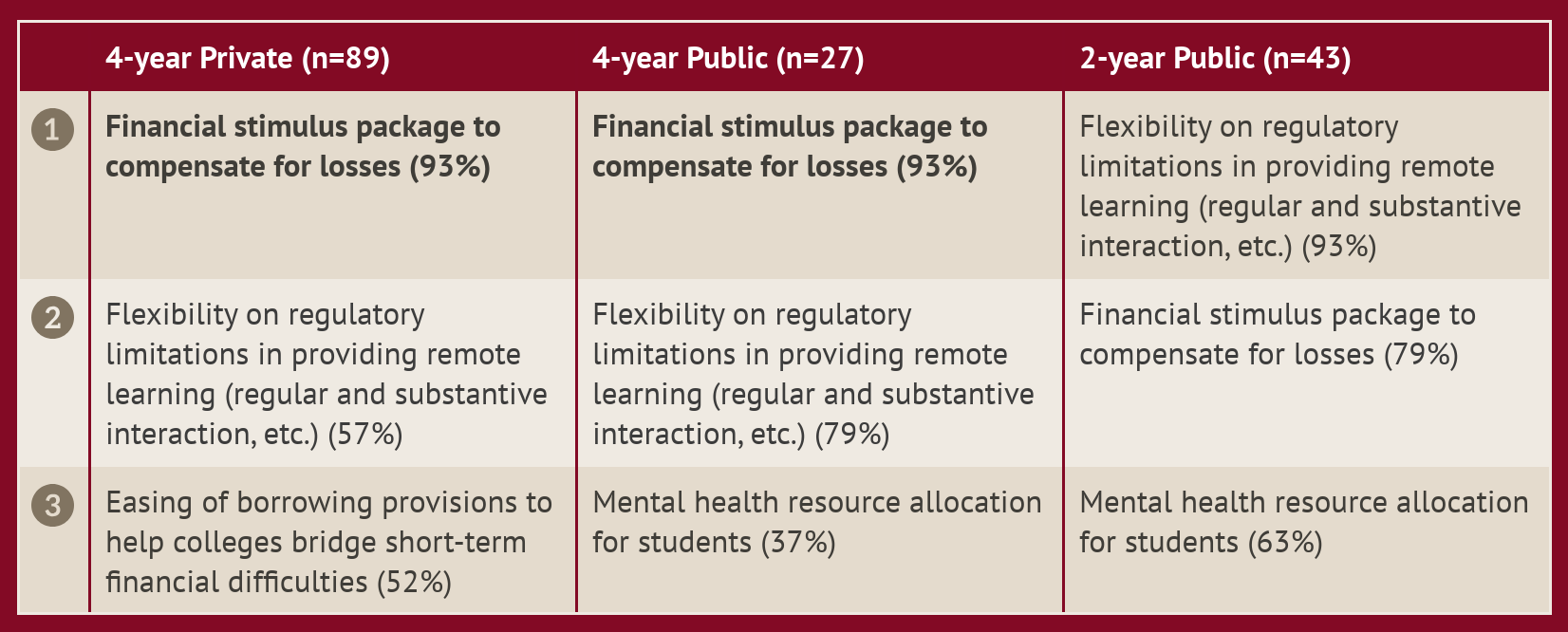

And when it comes to support from state and federal governments, as Congress and the Trump administration aim to put the finishing touches on a $2 trillion economic stimulus bill, presidents want two things above all others: money and regulatory relief.

Presidents of four-year public and private colleges overwhelmingly prefer stimulus money. That's not unimportant to community college leaders, but their greater preference right now, they say, is relief from regulatory requirements governing online and distance education, such as rules on regular and substantive interaction between instructors and students.

What's Ahead

Staben of Idaho said that while the survey seems to suggest that presidents are, by and large, focused on the right near-term issues and making the right calls so far, it didn't reflect the extent to which campus leaders should be looking ahead.

"The president needs to understand the operational situation and capture the things we've got to do now and delegate dealing with those things to the people responsible for them," he said. "What the president needs to do as a leader is insulate himself from the current crisis and ask, 'What is the future for my institution?' It's important to move the conversation to that vision piece."

Peter Stokes, managing director focused on higher education at Huron Consulting, said via email that the survey reflected what he and his colleagues are seeing in the market: "a mix of all-hands-on-deck to triage immediate challenges, coupled with a desire to push forward to important initiatives (especially related to enrollment strategy and professional program growth), along with a recognition that some of the changes perpetrated by this event may well be lasting and therefore folks may need to develop some new business models to accommodate the new reality."

Mitchell of ACE agreed with Staben that presidents need as soon as possible to "look out of the foxhole" and turn their attention to the future, beyond the immediate priorities. But that's hard when the future is as uncertain as respondents to the survey shows they clearly are, with 41 percent having no sense when on-campus operations will resume, Mitchell said.

"That really compromises the ability to do strategic planning."

When the presidents do look ahead, said Paul N. Friga, clinical associate professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a consultant to colleges on financial issues, their focus seems -- appropriately -- to be on financial issues. "The fiscal pressure is at a breaking point and it is time to make real change in higher ed spend -- administrative and academic," he said. "The crisis can break inertia that has resisted such change over the past decade since the last major recession."