Free Download

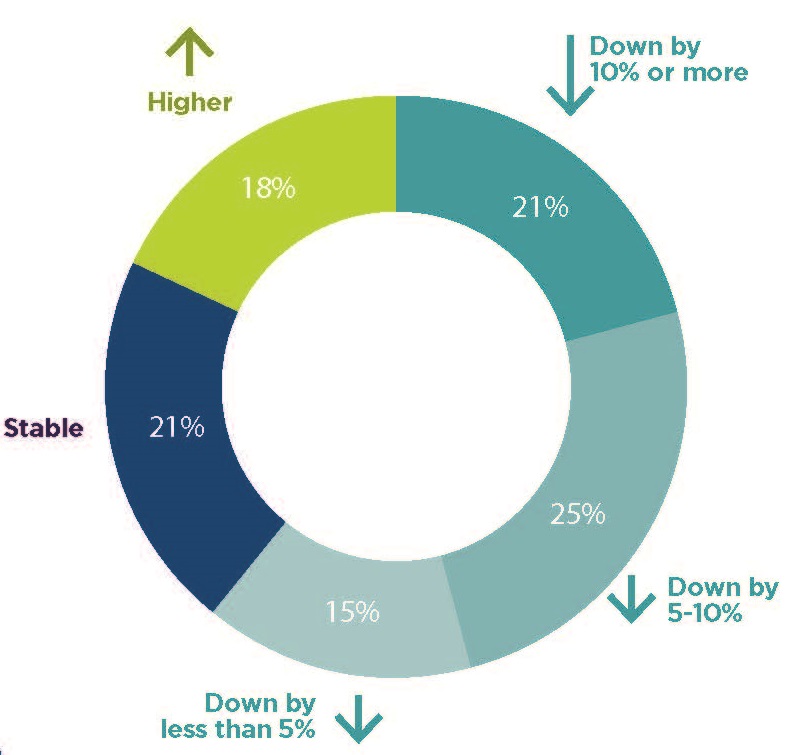

Six in 10 leaders of community colleges say their enrollments have declined in the past three years, including 21 percent who say enrollment is down by 10 percent or more, according to Inside Higher Ed’s 2017 Survey of Community College Presidents.

The survey, conducted by Gallup, is based on responses from 236 leaders of two-year colleges, who were queried about recruitment, the future of free community college and the emerging talent pool for new presidents, among other topics.

Although most presidents said their institutions have seen decreases in enrollment, 18 percent reported an increase compared to three years ago.

More About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed’s 2017 Survey of Community College Presidents was conducted in conjunction with Gallup. A copy of the report can be downloaded here.

Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys key higher ed professionals on a range of topics.

On May 10 at 2 p.m. Eastern, Inside Higher Ed editors Scott Jaschik and Paul Fain will present a free webinar on the results and take your questions. Sign up here.

The Inside Higher Ed survey of presidents was made possible in part by advertising from Ellucian, InsideTrack, Jenzabar, Pearson and VitalSource.

Many of these community college leaders say they’re focused on recruiting students and offering new programs.

Asked what steps they were taking to recruit more students, adding new campus programs drew the most response (81 percent), followed by adding options to ease student transfer (72 percent), increasing marketing spending (65 percent) and adding online programs (62 percent). Far fewer (38 percent) said they were freezing or cutting tuition.

Presidents who said their institutions had stable or increasing enrollment were more likely than their peers (48 percent to 34 percent) to say they were keeping tuition level or cutting it.

On the Campuses

At Michigan’s St. Clair County Community College, President Deborah Snyder has seen enrollment fall from about 5,200 in 2009 to about 3,700 this year. Some of that is due to the economy stabilizing and people preferring work to a classroom, but there are other reasons, she said.

“Community colleges by and large in the past have just figured that they’re going to draw from the community in which they reside,” she said. “What community colleges do is look at demographic numbers and project how many students they’ll get based on how many are graduating [high school]. But as the high school graduation number goes down, it’s no surprise our numbers are going down, too.”

Last year, the college began to boost recruitment in the area’s high schools by reaching out to counselors and making presentations to the traditional-age population, she said.

The college also decided to increase the number of sports offered to encourage more recent high school graduates to consider St. Clair as an option. The majority of students at the college are recent high school graduates. About 25 percent of St. Clair students are nontraditional.

“We’re adding sports and we built a big, beautiful field house,” Snyder said. “There are students who would come here if they thought there would be a real college experience. We’re trying to entice those students who maybe would be attracted to a four-year institution to come here first, and for parents the draw is financial. We’re saying you can save a lot of money coming to a community college for two years.”

St. Clair already offered athletics programs in men’s and women’s basketball, baseball, softball, volleyball and golf. But last year college officials added men’s and women’s cross country, and this fall men’s and women’s bowling and wrestling will be added to the list, said Pete Lacey, St. Clair’s vice president of student services. Tennis and women’s soccer are under consideration for the future.

Lacey said the college’s administrators are budget conscious and recognize their sports programs aren’t lucrative, but they’re optimistic the additional enrollment will offset any increases in cost.

Despite decreases in the number of high school graduates in the region, St. Clair is also seeing a boost from high school students taking dual credit courses at the institution. About 25 percent of St. Clair students, or about 1,000 students, are pursuing college credits while they’re in high school.

The Trouble With Transfer

The presidents’ focus on transfer appears to embrace cooperation over competition with other institutions.

“It’s so competitive,” said Snyder of St. Clair. “We’re not only competing with other community colleges [for enrollment], but we’re competing with online, state institutions and private institutions. I’d rather collaborate with them and work on articulation agreements than compete with the University of Michigan.”

Transfer does not always go smoothly, though, and far fewer students move to four-year institutions than initially say they plan to. Asked to rate the most significant barriers to transfer, 44 percent of two-year-college presidents cited as a “very significant” factor the lack of clear pathways to ensure the transfer of academic credit, followed by a lack of clear interest from public four-year colleges in supporting transfer students (26 percent) and in accepting such students (23 percent). Public colleges were rated more negatively on those counts than were private four-year institutions.

Transfer between Connecticut’s community colleges, the state’s regional public universities and the University of Connecticut has improved significantly over the years.

Manchester Community College’s students, for instance, are guaranteed admission to UConn if they meet a certain set of criteria, and legislation was passed a couple of years ago establishing seamless transfer and guided pathways for the state’s two-year students to about 20 programs in Connecticut’s four-year college and university system.

But problems may still arise, President Gena Glickman said, adding that it’s not uncommon for students to still lose credits when transferring or find they don’t have the right prerequisite courses to transfer despite articulation and seamless transfer agreements.

“It starts with the institution,” she said, adding that colleges have to clearly show students the program pathways they’ve created to ease transfer to four-year institutions, but it's also the responsibility of students to take advantage of those pathways.

Glickman said it’s her goal to eventually have an academic coach assigned to every one of her students at Manchester. Although that hasn’t happened yet, the college has been able to provide a coach for students on academic probation to help guide them through these choices.

Presidents’ Biggest Challenges

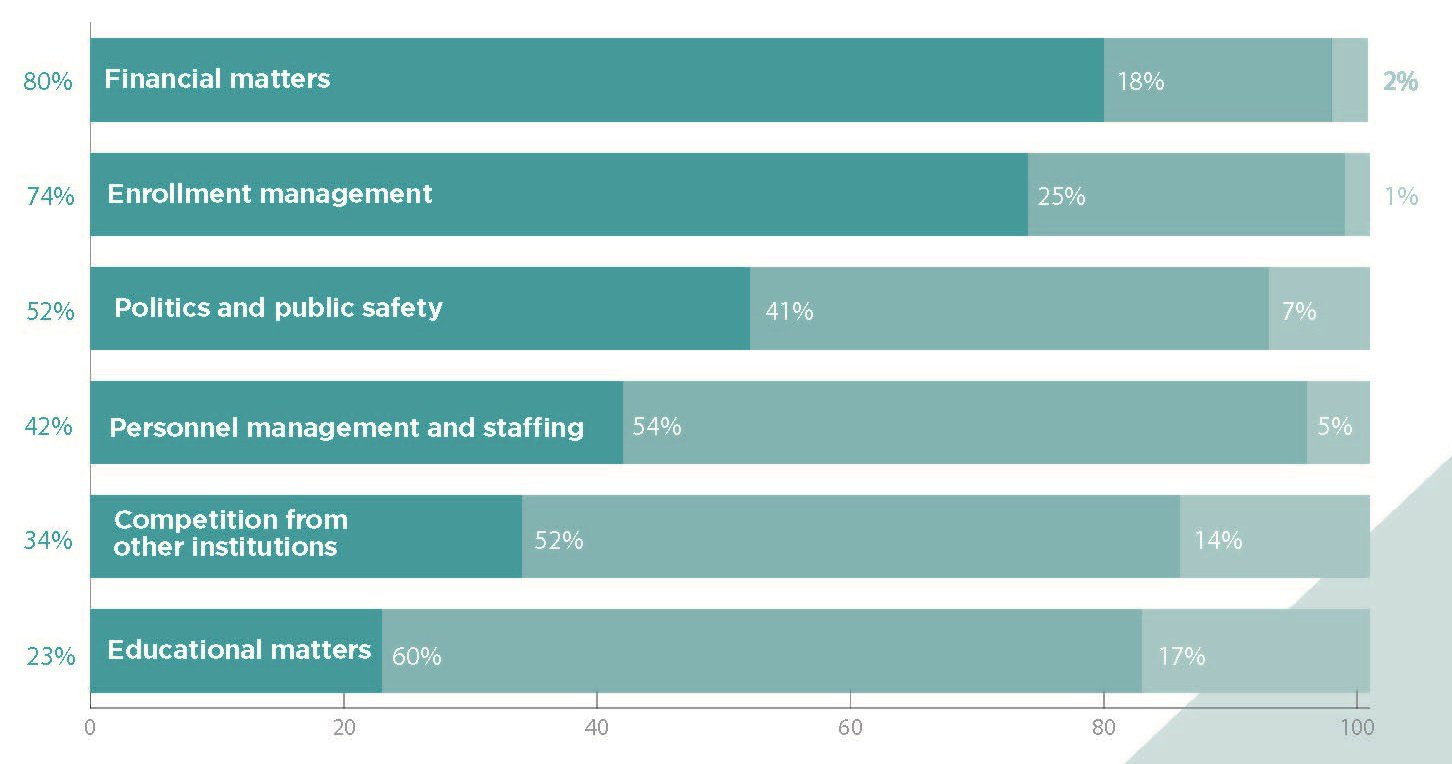

Asked to assess the significance of the challenges they face, money and enrollment topped the list.

Eighty percent called financial matters a “big challenge,” followed by enrollment management (74 percent), and politics and public safety (52 percent). Personnel, competition and academic matters lagged.

The Presidential Pipeline

The Presidential Pipeline

Beyond the challenges community college presidents are facing on their campuses, many leaders who responded to the survey said they are concerned about the future of their profession. Community college presidents were divided on the quality of the talent pool available to fill leadership positions like theirs.

Just 29 percent said they were impressed with the field of potential two-year leaders.

But Josh Wyner, executive director of the Aspen Institute’s College Excellence Program, said he’s not surprised that current presidents seem pessimistic about the talent pool for their profession. The Aspen Institute, which focuses on driving leadership to solve problems, also runs a fellowship to prepare aspiring or recently appointed community college presidents.

“There are a lot of very experienced presidents out there, [and] as people get more experienced and they look at the folks coming up behind them, they’re less certain those people are qualified,” he said, adding that the average age of presidents has increased by a decade in the last 20 years.

Seventy-seven percent of respondents to the Inside Higher Ed survey are between the ages of 50 and 69.

“The world in which community college leaders practice is changing fast,” Wyner said. “The complexity of the job makes it harder and harder to be prepared for the presidency.”

Wyner said today’s presidents are finding political discourse on their campuses becoming more difficult as the country divides along partisan lines, but they’re also facing an inability to control social media or messages during crisis moments and difficulties in lobbying for funding and state-based grants and appropriations.

“The expectations of all of the authorities that oversee community colleges are ramping up, and the demographics of communities are changing so more underprepared students are entering community colleges,” he said. “Being prepared in an environment where you’re asked to do more with less resources for a more diverse population is hard, and it’s hard to imagine people being prepared for that.”

Aspen recently completed its first fellowship for aspiring or new community college presidents. The highly selective yearlong program not only works to better prepare two-year leaders, but to also increase diversity in the field. Presidents surveyed said they were split on whether there are clear paths to the presidency, with 43 percent saying there aren’t.

The community college presidents surveyed said they were more pessimistic about there being a pool of qualified minority candidates than they were about the pool of qualified women candidates.

Aspen’s second-year fellowship class is made up of 68 percent women and 35 percent people of color, including 15 percent who identify as African-American, compared to 7 percent of sitting presidents. Ten percent are Latino, compared to 5 percent of sitting presidents, Wyner said.

“If sitting presidents believe they’re not seeing adequate talent in the pipeline and underrepresented minorities and women aren’t in the pipeline or in the presidency, then we have a lot of work to do with those groups so they’re prepared,” he said. “It’s about preparation and making sure our selection processes are equitable and fully consider the wide range of candidates.”

The Environment for Free Community College

Two-year-college leaders were also asked about how the changes in the national political landscape would affect the high-profile issue of free community college, like the plan President Obama suggested two years ago.

A majority of community college presidents -- 58 percent -- said there is very little chance of federal support for such a program, but that local initiatives like those in New York and California are likely to grow.

Forty-one percent of community college presidents said the idea is unlikely to spread at all.

Only 1 percent said they expected the idea to win continued federal support under President Trump.