Free Download

About 7 in 10 college and university presidents believe that the past year's sports scandals have damaged all of higher education and that institutions spend way too much on intercollegiate athletics -- but barely a quarter say their own campuses are susceptible to such scandals or overspend on sports.

Roughly two-thirds of public and private college presidents say they plan to vote for President Obama in November, and only 1 in 10 believe the Republican candidates for the presidency have laid out a helpful vision for higher education. (For-profit-college leaders disagree on both counts.)

And declining government support tops the list of concerns for presidents at all institution types, with more than 80 percent of presidents saying that potential cuts to federal student aid programs will be a major challenge for their institutions in the next two or three years.

Those are among the findings of Inside Higher Ed's second annual Survey of College and University Presidents, released today in advance of the annual meeting of the American Council on Education, in Los Angeles. A total of 1,002 campus chief executives, nearly a third of the 3,145 invited to participate, provided their views, with hearty response from across higher education's sectors and segments. The presidents were granted complete anonymity so that they could answer frankly, but their answers were coded by institution type, allowing for analysis of differences by sector in responses.

A report of the survey's results, prepared by Kenneth C. Green -- founder of the Campus Computing Project and a senior research consultant to Inside Higher Ed -- can be downloaded here.

Find Out More

Inside Higher Ed editors and

reporters and three college presidents will discuss the survey's results on Monday at the annual meeting of the American Council on Education in Los Angeles. Click here for more information.

Inside Higher Ed sponsored

a free webinar on the survey's results on March 22. To view a

recording of the event, click here.

Among other key results:

- The financial outlook for public and private colleges and universities is diverging after several years of cuts for all institutions. Public college and university presidents were more likely than their private nonprofit and for-profit peers to say they expected to face budget shortfalls in the next few years.

- Reflecting pressure on institutions to prove their value and show that their students are learning, presidents ranked issues of academic quality and student learning just below a set of financial concerns at the top of their lists of the biggest challenges facing their institutions. But while half of all campus leaders listed "student assessment and educational outcomes" as a "very important" issue, fewer than a third of presidents of public and private doctoral institutions did so.

- Just over one-third of college and university presidents rated their institutions as very effective at using data to "aid and inform campus decision making." Leaders of private doctoral universities (26.7 percent) and public baccalaureate colleges (27.7 percent) gave themselves the worst marks on that front, while more than half of for-profit-college chief executives said their institutions used data effectively.

- Slightly more than a third (36.9 percent) of all college presidents say they would stop awarding non-need-based financial aid if their competitors did, too. A slim majority of private doctoral university presidents (51.6 percent) said they would abandon such merit-based awards -- but only 33.4 percent of the leaders of public colleges and universities said they would.

The Effect of Sports Scandals

The past year was an eventful -- and often disturbing -- one for many big-time college sports programs, with major scandals unfolding at some of the most visible universities in the country, including Pennsylvania State University, Ohio State and Syracuse Universities, and the Universities of Miami and North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Because of their often tawdry nature, most notably the allegations of child sex abuse at Penn State and Syracuse, the controversies drew headlines far beyond the sports pages, and attracted the attention of high-profile critics like the historian Taylor Branch and Joe Nocera of The New York Times.

The scandals, combined with escalating concerns about rapidly escalating athletics spending and increased questioning of the amateur status of big-time college sports, prompted aggressive responses by presidents through the National Collegiate Athletic Association, which approved a series of reforms last fall with what, for the sports governing body, was lightning speed.

Asked a series of questions about athletics in the Inside Higher Ed survey, presidents expressed real concern about the impact of athletics scandals on the credibility of higher education generally. But at the same time, in what some observers see as a contradiction, they displayed confidence about the soundness and integrity of their own individual programs.

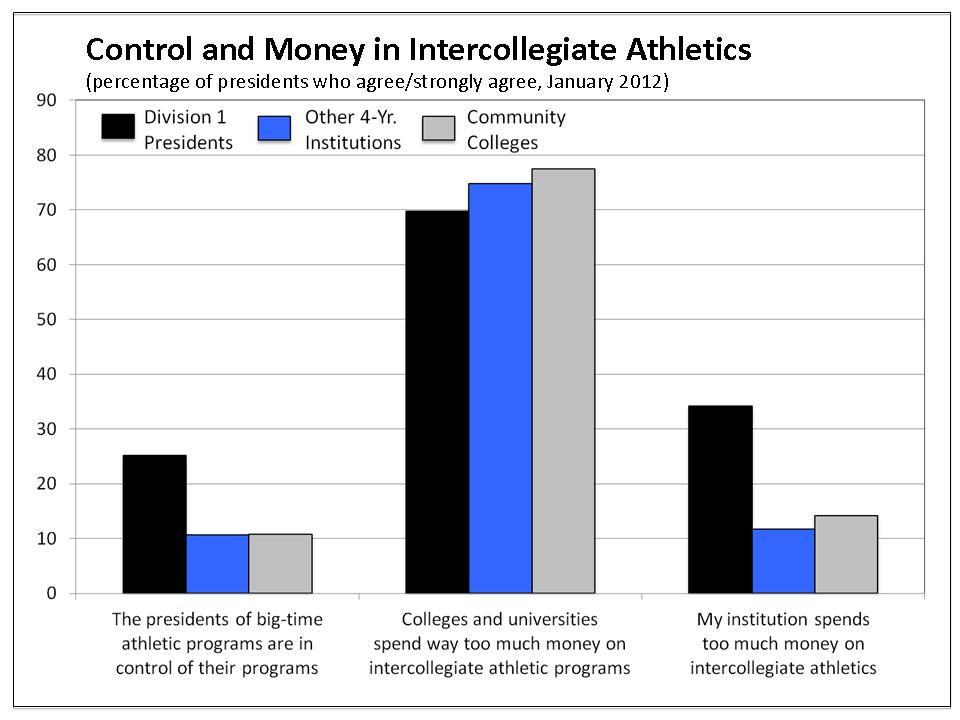

Roughly two-thirds of presidents over all said they believed the past year's scandals had "hurt the reputation of all higher education, not just the institutions involved," and an overwhelming majority (86.9 percent) said they did not believe that the presidents of institutions with big-time sports programs were "in control" of those programs. Three-quarters also agreed with the statement that "colleges and universities spend way too much money on intercollegiate athletic programs."

Those views were widely held across types of institutions, although some variation was evident. Presidents of the institutions most likely to have big-time sports programs -- public doctoral and master's universities -- generally agreed that the sports scandals had damaged higher education broadly, and even that college presidents are not in control of their athletics programs; a full 70.7 percent of presidents of public doctoral institutions and 86.3 percent of those at public master's universities said that presidents do not control their sports programs.

A smaller proportion of presidents of private doctoral institutions (58 percent), though, agreed or strongly agreed that recent scandals had damaged all of higher education, suggesting they may see themselves as less susceptible to sports-related taint than do others, despite the scandals that have unfolded at places like Syracuse and Miami.

About the Survey

The 2011-12 Inside Higher Ed

Survey of College and University Presidents is the latest in a series

of surveys of senior campus officials about key, time-sensitive issues

in higher education.

Inside Higher Ed collaborated

on this project with Kenneth

C. Green, founding director

of the Campus Computing Project.

The Inside Higher Ed survey

of presidents was made possible

in part by the generous financial

support of Datatel+SGHE, Hobsons, InsideTrack and Pearson.

That confidence was reinforced in the answers those presidents gave to a set of questions about the impact the sports scandals had had at their own institutions. More than 70 percent of private university presidents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that as the scandals at Penn State, Miami and elsewhere broke out last year, they were "confident that these types of events could not happen at my institution." (Another 13 percent of presidents of private doctoral presidents said the question was not applicable at their institutions, reflecting the fact that some of them do not sponsor highly visible or expensive sports programs.)

Public university presidents were less likely than their peers at private institutions to feel immune from sports scandal; fewer than half (46.8 percent) of public doctoral presidents (and 64 percent of public master's university presidents) said they were confident that scandals like those elsewhere "could not happen" at their institutions. But even at those institutions, the presidents appeared surprisingly confident about their ability to avoid sports controversies, given the 86.9 percent of chief executives who said presidents of big-time programs nationally are not in control of their programs.

That incongruity was also evident in the presidents' answers about sports spending. Compared to the 75 percent who said that colleges spend "way too much" on intercollegiate athletics, public doctoral university presidents were the only category of campus chiefs in which significant numbers said their own institutions spent too much on sports; 35.6 percent of them said so, compared to just 14.9 percent of all presidents, 19.2 percent of public master's college leaders, 16.2 percent of private doctoral university presidents, and 21.3 percent of private master's college presidents.

And in another section of the report, asked to assess a set of strategies that institutions might use to deal with budget limitations in the months ahead, just 19.8 percent of public college presidents and 14.2 percent of private college presidents said such cuts in athletics budgets were "currently under discussion" on their campuses; many more (30.5 percent at publics and 48.2 percent at privates) said sports budget cuts were "appropriately off the table."

The presidents of Division I institutions themselves displayed the same sort of disconnect about the conduct of their sports programs. Nearly 8 in 10 Division I presidents surveyed agreed that the past year's athletics scandals have damaged all of higher education, not just the involved institutions, and just a quarter (25.2 percent) agreed with the statement that "the presidents of big-time athletic programs are in control of their programs." A full half -- 51.2 percent -- also agreed that "scandals are inevitable in big-time college athletics," and 7 in 10 (69.8 percent) said colleges spend too much on intercollegiate athletics.

But nearly two-thirds of the 122 Division I presidents who answered the Inside Higher Ed survey expressed confidence that scandals like those of 2011 "could not happen" at their institutions, and 86.7 percent said their boards would back them if they had major conflicts with powerful coaches or athletics directors. Only a third agreed or strongly agreed that their own institutions spend too much on intercollegiate sports.

"The survey confirms the need for major reforms but demonstrates why they are so unlikely to occur," says William E. (Brit) Kirwan, president of the University System of Maryland and co-chair of the Knight Foundation Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics. "As long as the attitude is, 'Things are awful except at my institution,' the status quo will, unfortunately, prevail."

Adds James J. Duderstadt, former president and University Professor of Science and Engineering at the University of Michigan: "Most institutions believe they have in place systems to catch these things, until all of a sudden they come up short. If it can happen at Penn State and Ohio State and USC, it can happen to any of us." William C. Friday, president emeritus of the University of North Carolina and a founder of the Knight Commission, notes that an Inside Higher Ed review last year showed that nearly half of major college sports programs had been punished by the NCAA from 2001 to 2010. "It is just not accurate to say, 'College sports is in a terrible mess but my place is all right,' " Friday says.

Even as they concede that scandals in big-time college sports are damaging higher education, presidents appear to have little confidence that anything can be done about it -- and few seem interested in the government intervention that many outside observers believe is necessary to effect true change in collegiate athletics.

Fewer than a third of presidents in any sector agreed with the statement that "the NCAA's reform proposals for college athletics are likely to achieve meaningful success," and even the Division I presidents who approved those rules -- tougher academic standards for freshmen and for participation in NCAA championships, and moves to strengthen penalties against rule-breaking programs -- seemed pessimistic about reform, with 68 percent of Division I presidents disagreeing with that statement.

The chief executives soundly rejected the idea, embraced by many critics of college sports, that Congress or other government actors should step in in some way. A full three-quarters of all presidents disagreed with the statement that "Big-time college athletics cannot be fixed without government intervention of some kind."

The 2012 Election

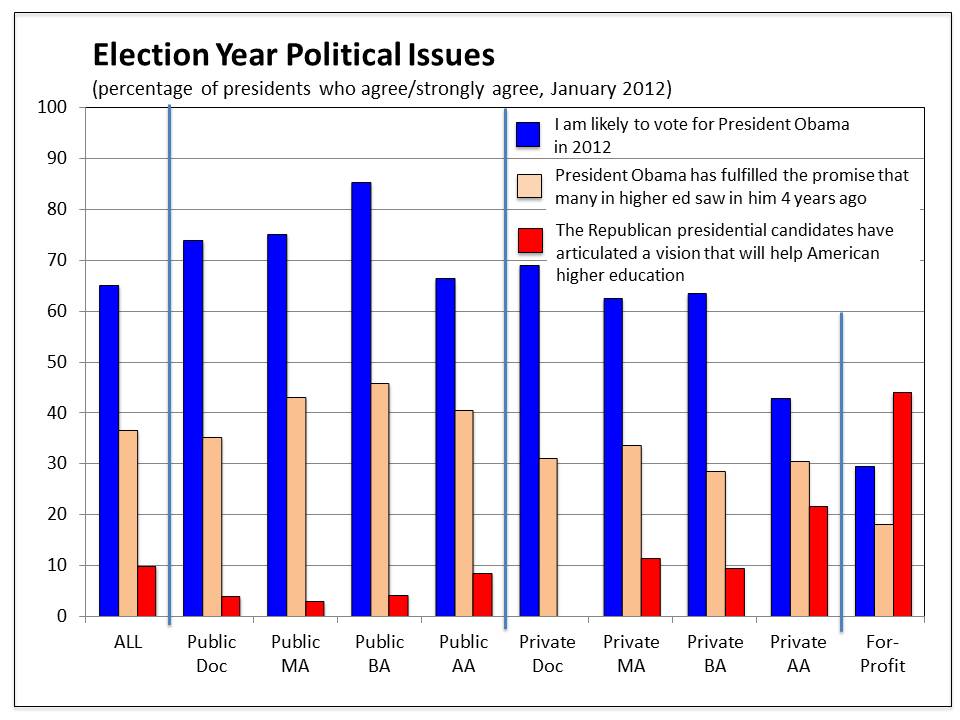

Most college presidents -- leaving aside those in for-profit higher education -- plan to vote for President Obama this fall, even if only a minority believe that he has fulfilled the promise for higher education that many of them saw four years ago.

President Obama has had strong ties to academe from the start, having taught at the University of Chicago, and gathering considerable talent from academe for his administration. He has also focused more than his predecessors on the goals of having more Americans go to college. He has backed huge infusions of funds, especially for community colleges, although Republicans in Congress have blocked much of what he has proposed.

In the Inside Higher Ed survey, 65.1 percent of college presidents said that they planned to vote for the president this fall. Among sectors, support was stronger in public higher education (75 percent at public doctoral and master's institutions, 85 percent at public baccalaureate institutions and 66 percent at community colleges). The lowest level of support was in for-profit higher education, where only 29 percent of presidents said they plan to vote for Obama this fall.

Asked if President Obama has "fulfilled the promise that many in higher education" saw for him four years ago, only 36 percent of presidents said yes. The figure was lowest in the for-profit sector (18 percent), which has clashed with the administration numerous times.

One reason American college presidents are backing Obama may be that very few of them see much of a higher education agenda coming from the Republicans. The presidents were asked to agree or disagree with the statement that "The Republican presidential candidates have articulated a vision that will help American higher education." (The survey was conducted before the recent controversy over one candidate, Rick Santorum, criticizing President Obama for urging all Americans to get a higher education, so those remarks didn't influence the results.)

Only 10 percent of all college presidents believed that the Republican candidates have offered a higher education vision, but that figure is inflated by a high proportion of yes answers from for-profit higher education (44 percent). The figures are much lower for the rest of higher education -- 4 percent among public doctoral institutions, 3 percent among public master's institutions, and not a single private doctoral university president agreeing.

Peter McPherson, president of the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities and former president of Michigan State University, is among those higher education leaders with strong Republican ties, having served in the Reagan and Ford administrations. He cautioned against reading too much into the view that Republicans have said little about higher education (which he didn't dispute). "The Republican primaries haven't focused much on education," he says. The Inside Higher Ed question "assumed that we would have had in the campaigns articulated a vision" on higher education issues by this point, and that just hasn't been the case, McPherson says.

He adds that there remains plenty of time for the Republican nominee to speak out on higher education -- and stresses the extent to which many higher education issues are bipartisan, noting the support of many Republicans for Pell Grants and research funding. McPherson also notes that -- however the campus presidents ultimately vote -- most of them "are very careful to be nonpartisan," and that (in the public sector especially) they seek to influence Republican and Democrat lawmakers alike.

McPherson says that he has reached out with ideas to some Republican candidates, but that this was in the same way he regularly reaches out to the Obama administration with ideas.

Steve Gunderson, a former Republican congressman from Wisconsin and the new president of the Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities, the chief lobbying group for for-profit colleges, says he too expected to hear more from the Republicans. But he cautions that the GOP candidate may not frame the issue as being about colleges. "For America to succeed economically, and for America to give everyone an equal opportunity, which are goals historically at the heart and soul of the Republican Party, you have to be willing to invest in education," he says. "But I think the GOP may come more [at these issues] by talking about meeting the skilled workforce needs of the American business community." For Republicans, a business-oriented approach to education is going to make more sense than going after "the higher education voting bloc, which is traditionally a Democratic voting bloc."

Gunderson says he isn't surprised that presidents of the for-profit colleges his organization represents are much more skeptical of President Obama than are their nonprofit counterparts. In part, he says, this is a logical outcome of the last four years. "The reality is that the Department of Education during the Obama administration has leveled some very strong attacks" on for-profit higher education, says Gunderson.

But he also says that -- regardless of the disputes of the last four years -- there may be a business orientation among many for-profit presidents that makes them more comfortable with Republicans. "By the very nature of being private sector," Gunderson says, "there tends to be a stronger allegiance and comfort with the private sector as opposed to the public sector."

A Split Financial Picture

Presidents have good reason to pay attention to politics this fall. When asked to list the issues that would be important to them over the next two to three years, financial concerns -- particularly the levels of government support -- topped their lists.

Across all sectors, presidents said one of the largest issues will be potential cuts in federal student aid, with at least three of four presidents at all institution types saying such cuts would be a highly important issue during the next two or three years. The number was particularly high among presidents of for-profit colleges, with about 89 percent of those institutions’ chief executives saying aid policies would be a major issue. Republican lawmakers in Congress have at various times called for cutting the Pell Grant program and ending subsidized loans, two changes that could dramatically alter almost all institutions’ bottom lines.

“The thing that worries me the most is really federal financial aid,” says John G. Morgan, chancellor of the Tennessee Board of Regents, which oversees six four-year universities and 13 community colleges. “If the Pell program is significantly limited or lessened, we’re going to struggle with that. We’re a relatively poor state, and we tend to attract more needy students than the University of Tennessee system tends to attract.” Morgan says he has told all of his presidents to develop plans for coping with potential reductions in federal aid programs, but notes that it would be a struggle for the state or for institutions to maintain current levels of access if the program erodes.

Few other financial issues cut across sectors and institution types the way federal student aid did, though about 65 percent of presidents of most types of institutions said that rising tuition prices and affordability, highlighted in President Obama’s State of the Union address, would be highly important issues in the next few years.

Elsewhere in the survey, aggregate data hide divisions across sectors and institution types, particularly between public colleges and universities, which are still dealing with the effects of the recession, and private institutions, many of which seem to have returned to stable footing, particularly doctoral and master's institutions. While most institutions took a financial hit in 2008 and 2009, this year’s survey results indicate that private institution presidents are much more optimistic than their public peers are.

Public institution presidents were more likely than other chief executives to cite budget shortfalls and cuts to state support as issues they are likely to confront in the next few years, a finding that comes as no surprise to those in higher education. About 85 percent of public institution presidents said they expected budget shortfalls in the next two or three years, compared to less than half of private college and university presidents. That number was even lower among private doctoral and master’s institutions. Public university presidents were also more concerned about federal research funding, which could be on the chopping block, than were private university presidents. While both depend on such funding, private universities are more likely to have alternative revenue streams funding research, such as corporate contracts and investment returns, Morgan said.

Colorado College President Jill Tiefenthaler said state cuts have undermined the financial model and public mission of public institutions. “Most publics are starting to look like the highly tuition-dependent colleges without significant endowments, which is a tough sector right now,” she said. While state cuts might be a reason for financially stable private colleges like Colorado to be optimistic -- after all, privates look like better bargains in the face of cuts to academic offerings and support services at public institutions -- the trends are bad for higher education in general, Tiefenthaler said.

While they may be less worried about budget cuts than are their public college peers, private nonprofit college presidents are plenty concerned about their ability to fill their classes. After potential cuts in federal student aid, private college leaders said they were most concerned about the not-unrelated issues of rising tuition/affordability (67.9 percent) and increased competition for students (66.5 percent).

Given the concern about budget shortfalls, particularly in the public sector, Inside Higher Ed asked presidents what strategies they used to reconcile their budgets. The most common response presidents listed was exploring collaboration opportunities with other institutions, which about 71 percent of presidents said their institutions were discussing.

Shifting more classes online (63.0 percent) and eliminating underperforming programs (62.6 percent) were also cited by many presidents. For almost every cost-cutting measure Inside Higher Ed asked about, presidents at public institutions were more likely to say their campuses were discussing the measure than were their private peers, again highlighting the divide between sectors. Presidents of public doctoral universities, which have received attention in recent years for what some say are bloated administrations, were also more likely than other leaders to say their campuses were in discussions about streamlining administrative positions (93.3 percent compared to a 58.8 percent average) and reorganizing and reducing administrative units (85.0 percent compared to a 55.6 percent average).

At the other end of the spectrum, presidents of private baccalaureate institutions were less likely than their peers to say their institutions were engaged in any given cost-cutting measure, which Tiefenthaler said is a combination of the fact that they started out with less to cut and the fact that many have been in a relatively stable financial position for at least a year. The survey did not touch on measures presidents took in the past few years to increase revenue, Tiefenthaler noted, such as expanding enrollment and creating new professional master’s and distance-learning programs. (Many presidents and business officers reported that their institutions had done so in Inside Higher Ed's 2011 surveys of those groups.) Given the resistance that cuts often face, she said, many presidents might have found more success pushing revenue-generating initiatives.

Asked to identify potential budget-balancing strategies that "should be but are not being discussed" on their campuses, presidents focused most heavily on employment policies and practices -- not surprising in an enterprise where a large majority of the money goes to compensating people. Aggressively promoting early retirement programs (28.7 percent), increasing teaching loads for full-time faculty (26.2 percent), and revising tenure policies (20.5 percent) were in the top six, along with exploring collaboration with other institutions on administrative services (27.1 percent), outsourcing more administrative services (24.3 percent) and eliminating underperforming academic programs (24.1 percent).

Presidents indicated that they are at a breaking point when it comes to cuts. Across the board, most presidents also said the budget cuts of the past few years did not do major damage to the quality of their academic programs (85.9 percent) and campus operations or support services (71.6 percent). The only major casualty of cuts so far, they said, was staff morale, which 48.7 percent of presidents said was damaged.

At the same time, about 80 percent of presidents said they could not make additional significant spending cuts without hurting quality. That number was higher at public institutions than private institutions, with 42 percent of private doctoral university presidents saying their institutions could take deeper cuts, a number that raises questions about the need for continued tuition increases.

“Forty-two percent of private doctoral university presidents say they can take significant additional spending cuts without hurting the quality of the academic enterprise,” said John F. Burness, visiting professor of the practice in the DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy at Duke University and a longtime administrator there and at other public and private colleges. “If that’s the case, why does tuition continue to go up?”

In general, presidents do not see the financial picture improving for public institutions any time soon. Eighty-eight percent predict that state budgets will remain flat over the next five years, and 74 percent said that state leaders should be more willing to consider tax increases to address shortfalls. Except for those at private associate and for-profit institutions, at least 74 percent of presidents said substantial tuition increases were the best way for public institutions to sustain quality programs.

Academic Quality

Significant attention has been paid in the last year to the academic quality of undergraduate education, driven in large part by the publication of Academically Adrift, which questioned the extent to which students were gaining knowledge as they progressed through higher education. The chorus of concern -- expressed by the Obama administration, leading foundations and a slew of allies -- about "college completion" has put pressure on colleges and universities, from another angle, to ensure that students are making progress toward credentials.

It stands to reason, then, that presidents put academic matters high on the list of challenges facing their institutions (topped only by the financial issues discussed above). Just over half of all presidents (53.8 percent) rate "maintaining the quality of academic programs" as a very important challenge for their institutions, with public college presidents likelier than their private college peers to think so (presumably because of pressing concerns that state funding cutbacks will erode their quality).

But the survey reveals that presidents of different types of institutions have differing concerns about academic quality going forward. Presidents of community colleges (83.3 percent) and for-profit institutions (63.6 percent), not surprisingly, are much likelier than their peers to say that "remediation and student readiness for college" is a very important challenge for their institutions, although more than 4 in 10 leaders of public master's and baccalaureate institutions say the same.

While more than half (53.4 percent) of all campus chief executives cite "student assessment and educational outcomes" as a very important challenge for their institutions, presidents of public and private doctoral institutions (32.2 percent and 32.3 percent, respectively) and private master's universities (42.7 percent) were far less likely than others to do so.

And while three-quarters of presidents graded their institutions as highly effective in "providing a quality undergraduate education," they were on the whole far less upbeat when asked about how they did on matters that students and parents might consider important elements of that education. For instance, 59 percent of presidents over all said their institutions were highly effective at preparing students for employment, and the numbers were much lower for public doctoral (36.2 percent) and public master's (48.2 percent) institutions. Those gaps could cause problems as more states move to fund institutions based on outcomes.

And asked to rate their colleges' effectiveness in offering advising and other support services for undergraduates, just 42.8 percent of presidents gave themselves high marks, with private institutions scoring themselves better than publics and for-profit presidents (at 58.8 percent) best of all.

Among other findings in the survey:

- Presidents did not give particularly high marks to their campuses' investments in technology. Asked to rate the effectiveness of technology-related spending in areas ranging from student recruitment to student services to data analysis, none of the categories had more than half of campus leaders score them "strongly effective." Library resources came closest, with 49.6 percent, followed by technology related to online (42.6 percent) and on-campus teaching and instruction (42.1 percent), and administrative systems (39 percent). Technology spending related to research and scholarship (21.3 percent) and development (23.7 percent) got the lowest rating. For-profit colleges were something of an exception here, with more than half of presidents of those institutions rating their investments as strongly effective in four areas: student recruitment, on-campus teaching and instruction, online/distance programs and library resources and services.

- Although critics outside and from within higher education have questioned the effectiveness of accreditation, more than 6 in 10 college presidents say both regional and specialized accreditation make "a significant contribution to the quality" of their academic programs. The leaders of public and private doctoral universities, however, are far more critical of regional accreditation, with just 43.4 percent of public doctoral university presidents and 35.5 percent of private research university chiefs agreeing with that statement. Two-thirds of presidents agree that in their efforts to assess student learning, accrediting agencies have "issued mandates without offering useful or viable methodologies to do so."

- Just one-tenth of presidents agreed with the statement that "my institution makes too many decisions mindful of our standing in the U.S. News rankings of colleges."

- Fewer than a third of presidents believe that in incidents involving the Occupy movement and other student-led efforts, "campus police at many colleges have been too quick to crack down on peaceful protests."