Free Download

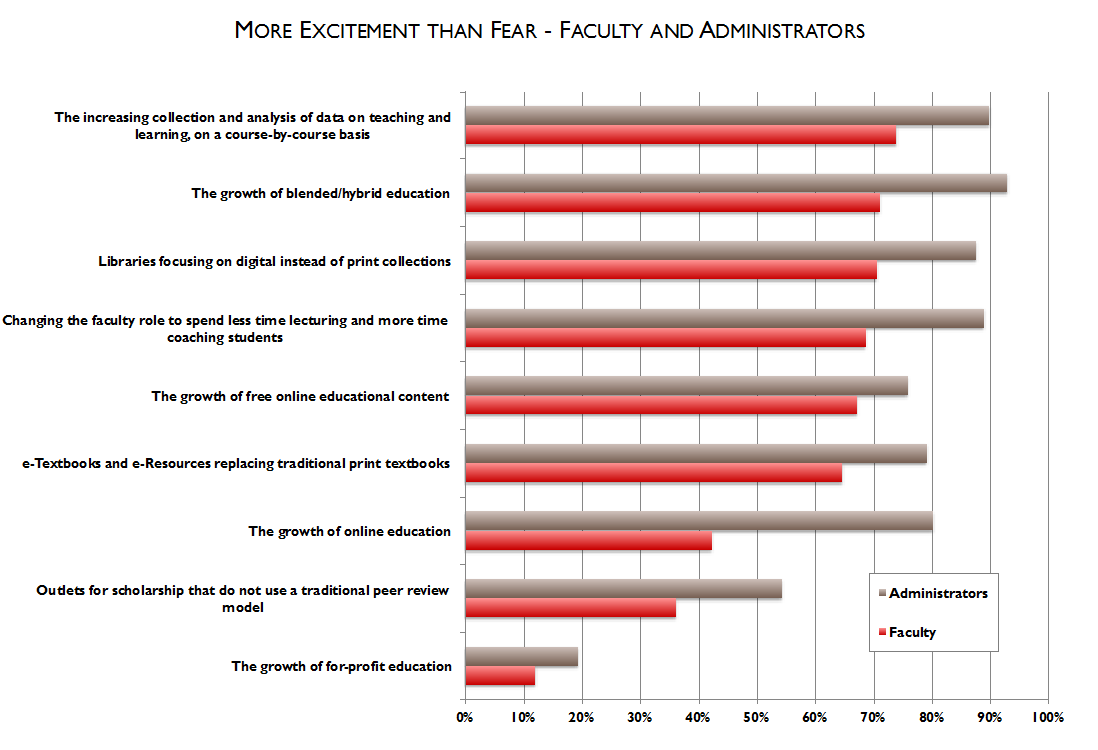

Professors occasionally get lampooned as luddites responsible for the famously slow pace of change in higher education. But in truth the majority of professors are excited about various technology-driven trends in higher education, including the growth of e-textbooks and digital library collections, the increased use of data monitoring as a way to track student performance along with their own, and the increasingly popular idea of “flipping the classroom.”

However, other technology trends are more likely to make professors break into a clammy sweat. These include the proliferation of scholarship outlets operating outside the traditional model for peer review, the growth of for-profit education, and the intensity of digital communications. The digital era has brought to the surface other tensions as well, particularly differences in how professors and academic technology administrators perceive how broader technological changes are affecting their campuses and how they should feel about it.

These are some of the findings in the second of two reports from surveys conducted by Inside Higher Ed and the Babson Survey Research Group. The first report, focusing on faculty views of online education, was published in June. A PDF of the new, second report can be downloaded here; the text of the report can be viewed here.

The survey relied on the responses of 4,564 faculty members, composing a nationally representative sample spanning various types of institutions; and 591 administrators who are responsible for academic technology at their institutions.

The faculty members’ net-positive outlook on several tech-related pedagogical trends suggests that student performance feedback loops and “flipping the classroom” are durable enough to outlast their current buzz. “The increasing collection and analysis of data on teaching and learning on a course-by-course basis” garnered the most enthusiasm of any of the excitement/fear questions in the survey, with 74 percent of professors saying it is, on balance, a good thing.

"Digital Faculty: Professors and Technology, 2012" is the second of two surveys of college professors and academic technology administrators about faculty attitudes about and approaches to technology. A PDF copy of the study report can be downloaded here. To read the text of the report, click here.

On Sept. 24, Inside Higher Ed sponsored a webinar to discuss the results of the survey of faculty views on technology, with Inside Higher Ed editors and bloggers analyzing the findings and taking audience questions. The recording can be viewed here

Inside Higher Ed collaborated on this project with the Babson Survey Research Group.

The Inside Higher Ed/Babson survey of faculty views on online education was made possible in part by the generous financial support of CourseSmart, Deltak, Pearson and Sonic Foundry.

The counterargument has been that this trend could lead to an overreliance on data-based metrics to assess not only student performance but teacher performance, leading to a No Child Left Behind-like regime at many colleges, especially public ones. But the vast majority of professors seem to think that the advantages of Big Data in the classroom outweigh the hazards.

As for “flipping the classroom” -- that is, banishing the lecture and focusing precious class time on group projects and other forms of active learning -- a decisive majority of professors seem to be on board. Asked their feelings on the notion of “changing the faculty role to spend less time lecturing and more time coaching students,” 69 percent said they were excited more than fearful.

The survey did not ask about the specific anxieties behind these responses. Perhaps some professors feel more comfortable doing research than engaging with students, and use the lecture as a crutch. In any case the findings of this survey suggest that most faculty members do not fear the prospect of “coaching” students rather than talking at them.

Ambivalence about Digital Content

Some technology-driven movements have caused tension, particularly in academic publishing.

In general, professors are pro-digital. A decisive majority, 71 percent, said the prospect of “libraries focusing on digital instead of print collections” makes them more excited than fearful (which may come as a surprise, given occasional reports of faculty protesting the removal of print collections from campus libraries). And 65 percent said they were excited about “e-textbooks and e-resources replacing traditional print textbooks.”

But professors remain uneasy about scholarly publishing outlets that eschew “traditional” models of peer review. Asked for their gut reaction to the emergence of “outlets for scholarship that do not use a traditional peer-review model,” 64 percent of professors said it mostly filled them with fear. (Administrators were far more enthusiastic, with 54 percent saying they are excited about this.)

As “open peer review,” post-publication review and other alternative models have gained momentum, would-be reformers have occasionally called for an end to the old system -- calling it tedious, cabalistic and, by now, unnecessary -- and inevitably provoking a heated debate about quality control.

Kathleen Fitzpatrick, the director of scholarly communication at the Modern Language Association, has been at the center of such debates. In her latest book, she argued for a new model of peer review that leverages wikis and other technological apparatuses to improve the process.

Fitzpatrick says that when considering "outlets that do not use a traditional peer review model," many professors might be failing to distinguish between alternative models of peer review and no peer review at all. "Frankly, though, I'm quite enthused to hear that over a third of respondents are excited by the possibilities of publications that use something other than a traditional peer review system," she told Inside Higher Ed via e-mail.

For the rest, it is reasonable to assume that much of their fear revolves around the assumption that alternative methods of vetting or filtering academic articles will not be as reliable as traditional peer review.

Textbook companies have tried to fuel similar skepticism about the quality of open educational resources, or OER. But according to the survey professors seem to be less concerned about quality control in the context of OER: 67 percent said they are excited about "the growth of free online educational content."

Fewer seem interested in producing such content, though. Just under 50 percent said they “created digital teaching materials/open educational resources,” such as lecture recordings, even occasionally. Only 20 percent said they do so regularly.

This does not necessarily amount to hypocrisy on the part of professors. Just because they are excited about a trend does not mean they have to participate. In some cases it might not be appropriate. In others it might not be an option.

But it could be that colleges are just not making it worth their while. Only 27 percent of faculty respondents said they believe their institution “has a fair system of rewarding contributions made to digital pedagogy.” That roughly accords with the proportion who regularly record and share lectures and other digital resources (20 percent) and those who have ever published novel forms of digital scholarship such as visualizations or game-based projects (22 percent).

Producing digital work also might not be the best career move. While 65 percent of professors said that online-only scholarship “can be equal [in quality] to work published in print,” only 13 percent said they believe such work is given the same respect in tenure and promotion decisions. Meanwhile, 57 percent of professors said online-only scholarship should be given equal respect, with only 13 percent actively disagreeing.

Using the LMS

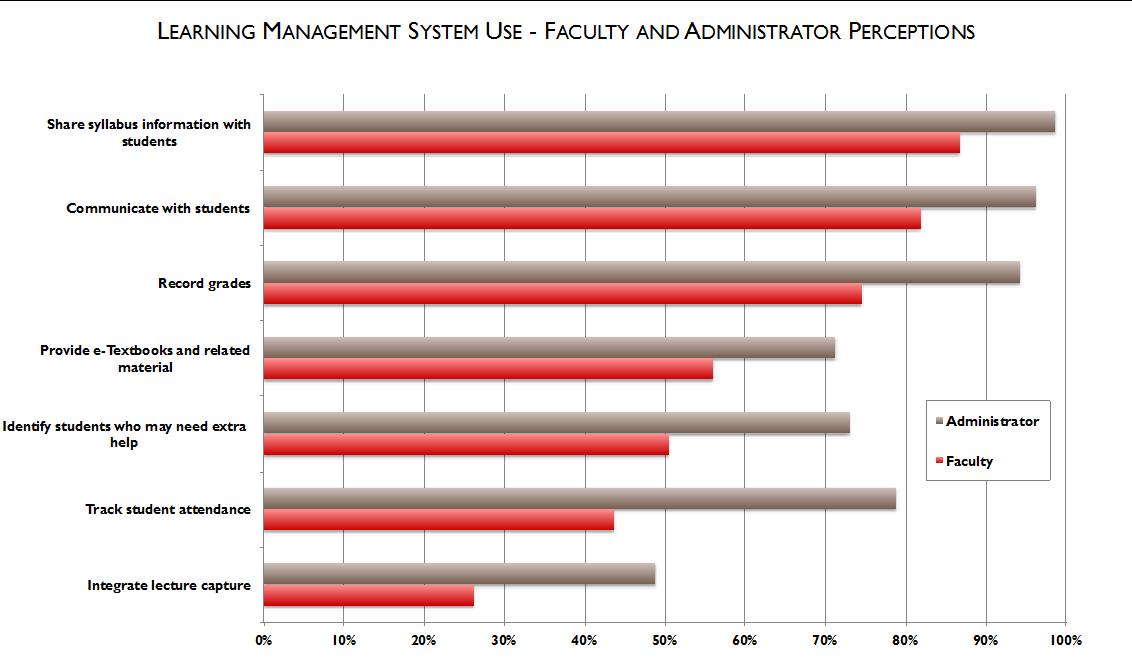

The learning management system, or LMS, is the nexus of traditional and online education. Not all colleges hold courses online, but virtually every college has an LMS. And since the online platforms can serve as a vehicle for other digital teaching tools, the ways the LMS are being used on a particular campus -- and the ways it is not -- are a pretty good indicator of technology buy-in of an institution and its faculty.

But fewer professors are using the LMS than administrators think.

Administrators believed that 73 percent of the professors at their institutions used data logged by the LMS either “regularly” or “occasionally” to identify students who need extra help. This would be true if every professor who expressed enthusiasm about the availability of fine-grained classroom data actually used those data. In fact, only 51 percent of faculty reported doing so.

About half of the administrators estimated that professors regularly or occasionally posted video-recorded lectures into the LMS, but just 25 percent of the faculty respondents actually do. Nearly 80 percent of administrators said their faculty members regularly or occasionally used the LMS to track student attendance; the professors clocked in at 44 percent. A whopping 94 percent of administrators believed professors recorded student grades in the LMS; the actual faculty rate was 75 percent -- high, but hardly unanimous.

“Institutional administrators’ perception of faculty use of LMS systems is not a good match to the reality of faculty usage,” wrote I. Elaine Allen and Jeff Seaman, co-directors of the Babson Survey Research Group, in a summary of the findings. “Administrators perceive a much higher degree of faculty use of LMS systems for every dimension than faculty actually report.”

At the same time, the administrators did seem to have a pretty good idea of how many professors were devoted LMS users. For example, while administrators overestimated by 22 percent the rate at which instructors use the LMS to identify struggling students, their guess about how many do so “regularly” (31 percent) was spot-on. They underestimated the percentage of instructors who upload lecture videos to the LMS by 3 percentage points, and they lowballed the percentage who were assigning e-textbooks through the LMS by 13 percentage points.

Over all, the discrepancies between administrative and faculty perceptions of LMS usage were largely in their estimations of “occasional” usage. In many cases, the administrators’ estimates for such casual LMS usage were vastly optimistic.

Over all, the discrepancies between administrative and faculty perceptions of LMS usage were largely in their estimations of “occasional” usage. In many cases, the administrators’ estimates for such casual LMS usage were vastly optimistic.

The 'Always-On' Lifestyle

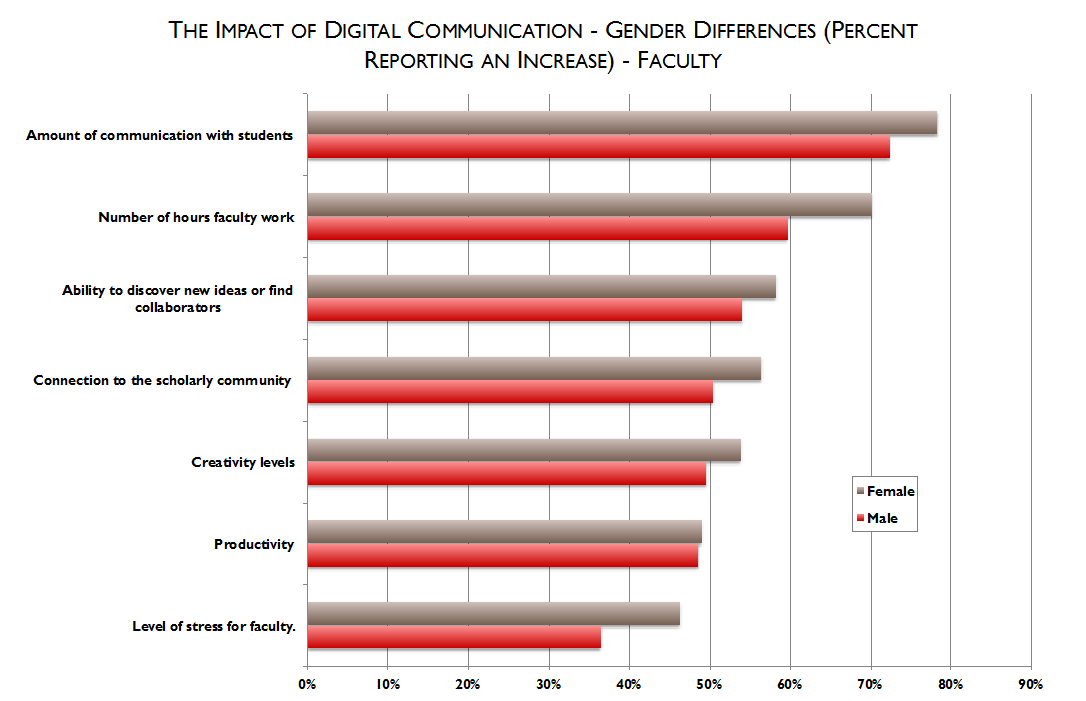

The advent of the “digital era” has not made every professor’s job more stressful, but 41 percent said it has done so for theirs. And while nearly half the faculty respondents said digital communications have made them more productive, very few said it has reduced their stress levels (16 percent) or hours on the job (19 percent).

This was particularly true of the women in the survey. Female professors were 10 percentage points more likely to report higher stress and hours worked as a result of digital communications.

Cathy Ann Trower, director of the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education at Harvard University, says it makes sense that the ease and expectations around digital correspondence would affect the professional lives of female academics disproportionately.

“I think women often feel more compelled to be immediately responsive to students and colleagues than men do,” she wrote in an e-mail.

“Quite frankly, women tend to have more difficulty saying no -- and that includes demands that are now being made via technology,” added Trower. “I know that, personally, I'm getting more requests than ever (to review papers for publications, to speak, online surveys, etc.) and I think that's in part a function of how much easier it is to reach out, quickly, to people.”

“Quite frankly, women tend to have more difficulty saying no -- and that includes demands that are now being made via technology,” added Trower. “I know that, personally, I'm getting more requests than ever (to review papers for publications, to speak, online surveys, etc.) and I think that's in part a function of how much easier it is to reach out, quickly, to people.”

As for many working people, the intensification of the professional lives of college professors can be measured by the length of their e-mail queues. In general the faculty respondents guessed that they received between 11 and 50 work-related e-mails per day — with 33 percent receiving fewer than 26 e-mails and 34 percent getting 26 to 50. (More than 20 percent of professors said they got north of 50 e-mails on a typical day, and an unfortunate 6 percent said their daily haul exceeded 100.)

About 37 percent of professors said they got more than 10 e-mails per day from students. (Most got fewer than 25.) Most felt the need to reply briskly: most return at least 90 percent of student e-mails within 24 hours.

Professors teaching online or “blended” courses reported getting more daily e-mails from students, but even among them it was rare to get more than 25 student e-mails per day.

In terms of discipline, the daily onslaught heralded by the digital era seems to have been most merciful to professors of the natural sciences. They reported increases in stress at a rate of 33 percent — low, especially when compared to the 47 percent of humanities and arts professors who said their lives had become more stressful. Social science professors reported similarly high levels of stress, while math and computer science professors were largely spared.

Adding insult to injury, the social science, arts and humanities professors who reported the greatest increases in stress also reported relatively low gains in productivity and creativity compared to their colleagues in other disciplines — particularly those teaching in professional and applied science programs.

For the latest technology news and opinion from Inside Higher Ed, follow @IHEtech on Twitter.