Free Download

Fewer than 10 percent of college human resources administrators are greatly concerned that too many campus officials are retiring and taking their institutional knowledge with them -- while nearly three times that many worry that older faculty members are failing to make way for the next generation of professors.

Chief HR officers take a relatively dim view of the role of employee unions on their campuses and in higher education generally, with more than three-quarters saying that the unions hamper their institutions' ability to redeploy people and restrict their administrators' ability to reward strong -- and punish poor -- performance.

And while nearly 6 in 10 HR leaders say they are in the "inner circle of advisers" for their presidents and are sought out for strategic guidance on employee issues, just 43 percent are official members of the president's cabinet at their colleges and universities, suggesting that human resources administrators have a ways to go in achieving the status that many of them seek in higher education.

Those are among the findings of Inside Higher Ed's first-ever Survey of College and University Human Resources Officers, released today in advance of the annual meeting of the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources in Boston. (A PDF copy of the report can be downloaded here. The survey, conducted in July and August 2012, was completed by a total of 324 campus and system chief human resources officers. Few HR officers from for-profit and two-year private nonprofit institutions completed the survey, so their responses were not explored in depth.

Like Inside Higher Ed's other surveys of administrators in higher education -- presidents, provosts, chief business officers and admissions directors -- the survey of chief human resources officers aims to solicit the voices of key constituents of key issues facing an industry in transition.

About the Survey

The new Inside Higher Ed Survey

of College & University Human Resources Officers is the fifth in a series of surveys of senior campus officials about key, time-sensitive issues in higher education.

On Monday, Oct. 8, Inside Higher Ed will present a free webinar to discuss the results of the survey. Editor Doug Lederman will be joined by two thoughtful HR leaders -- Sabrina Ellis of George Washington University and Judi McMullen of Cuyahoga Community College -- to share and analyze the results and take your questions. To register, please click here.

Inside Higher Ed collaborated

on this project with Kenneth

C. Green, founding director

of the Campus Computing Project.

The Inside Higher Ed survey

of chief HR officers was made possible in part by the generous support of Ellucian and TIAA-CREF.

The HR survey, more than the others, also seeks to gauge how human resources officials see their own roles. That's partly because of a widespread sense -- shared by many HR administrators themselves, the survey data show -- that human resources leaders on some campuses are not seen as essential contributors to strategic missions and discussions, even though as much as three-quarters of their institutions' budgets are tied up in employee salaries, benefits and programs for which the HR directors are directly, and often primarily, responsible.

Of all the employee-related issues facing higher education right now, in this period of economic turmoil and retrenchment, none has as much visibility as retirement. But exactly what the retirement "issue" is depends on one's point of view. Many recent reports have expressed concern about the graying of the academic work force and the perception that colleges and universities are poised to lose too many senior-level workers with reams of institutional history and knowledge. Others paint a scenario in which too many older professors are staying on in their jobs longer and longer, creating a logjam that blocks the path for new Ph.D.s and inhibits colleges' ability to refresh their faculties.

And still others worry about the potentially huge financial liabilities that retiree health and other benefits pose for their institutions.

In previous Inside Higher Ed surveys, business officers and presidents put retirement-related issues relatively low on their lists of concerns.

The survey of chief HR officers follows that pattern: asked several questions about their levels of concern related to various retirement-related issues, survey respondents, by and large, expressed relatively little worry about most of them.

As seen in the chart below, chief human resources officers were far likelier to express little concern than they were great concern about a range of potential retirement issues, such as whether too many administrators and staff members were retiring, whether their colleges were offering sufficient incentives to their employees to retire, and whether pension costs for retirees "comprise a huge expense or balance sheet liability for my campus."

The issues about which respondents cited the most concern were that "too many of our faculty are staying on past the traditional retirement age, not making room for the next generation of professors" (29.2 percent great concern, 16.8 percent little concern) and that retiree health care costs pose a big financial problem (26.6 percent great concern, 39 percent little concern).

The numbers vary quite a bit by sector and segment of higher education. For instance, while just 9.4 percent of all HR officers in the survey said they were greatly worried about replacing retiring non-academic employees, about twice that many respondents at public doctoral institutions and public master's institutions said so, while fewer than 5 percent of HR directors at private doctoral and private baccalaureate institutions.

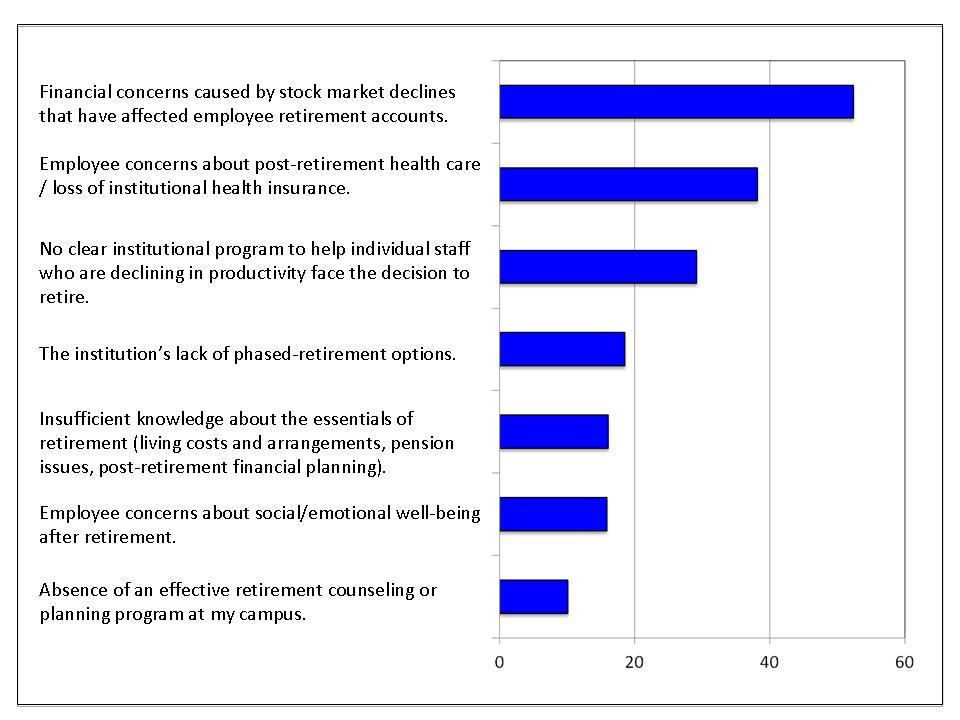

Respondents were also queried about the main barriers they saw to employee retirement at their institutions. In general they cited financial factors: employees' worries that their own retirement nest eggs had been reduced (if not devastated) by recession-related stock market declines (52.4 percent cited "significant concern"), and concerns about post-retirement health care or loss of institutional health insurance (38.2 percent), since many colleges do not offer post-retirement health benefits to their employees.

Assessments of the Barriers to Retirement

(percentage reporting 6/7; scale 1=not significant, 7=significant)

Just one in six respondents (15.9 percent) cited employee concerns about their emotional or social well-being as a barrier to retirement -- suggesting that in answering, HR officers were thinking far more about non-academic employees than faculty members, since this question didn't differentiate. "That is probably true on the staff side, but we know on the faculty side that it's really much more about their identity and their life's work," says Frank A. Casagrande, whose Casagrande Consulting works with colleges and universities on compensation, benefits and other employee matters. "For faculty members, work has never been about the money, so why should retirement be about money?"

Paul Yakoboski, a principal research fellow at the TIAA-CREF Institute, says that research it published last year on faculty motivations for retirement divides professors who plan to work past normal retirement age into two camps: those who are "reluctantly reluctant" to retire and those who are "reluctant by choice." Three-quarters of the former cite personal finances and about half cite the need for employer-provided health insurance as reasons for staying.

The latter group, however, is far likelier to cite the fulfillment their work provides (90 percent) and their belief that they remain effective (74 percent), and they are twice as likely as the "reluctantly reluctant" to say they would miss their colleagues and have "no attractive alternatives" for how they would spend their time. "It's not about the finances -- it's about 'who I am,' " says Yakoboski. That's why it's important for institutions concerned about faculty retirements to focus as much on helping would-be retirees with emotional and social issues as with providing financial incentives, he says.

Skepticism of Unions

If demographic trends and the decline in individuals' financial situations have put retirement in the spotlight, another set of forces -- state fiscal woes and political battles -- are likely to make employee unions a topic of contention in the months ahead. President Obama and his Republican opponent, Mitt Romney, have very different stances on the role of public employee unions, and their appointments to the National Labor Relations Board, depending on who sits in the Oval Office on January 20, could create drastically different climates for the state of collective bargaining for some groups of instructors and graduate students at private colleges.

And while it's possible that the November election may produce more governors who follow the lead of Wisconsin's Scott Walker and Ohio's John Kasich in seeking to rein in the influence of public employee unions, continued cutbacks in state funds and more years of no salary increases for campus employees may encourage more faculties and staffs to seek collective bargaining to try to bolster their causes.

If they do, they may find a chilly climate on campuses, if the survey responses are any indication. Between 10 percent and about a third of chief HR officers reported that they had unions on their campuses representing various groups of employees, with significant variation by sector and segment (almost two-thirds of community college human resources officers said their full-time faculties were unionized, compared with less than 7 percent of private colleges, for instance).

Respondents who reported that their campuses had unions were asked to assess the role they play locally, and all respondents were queried about the impact of unions in higher education generally.

The numbers were comparable -- and generally critical. More than 4 in 10 respondents said they believed that unions had "helped to secure better salaries and benefits than might otherwise be provided" (58 percent disagree), and roughly a third agreed that unions promote fairness in the treatment of employees.

But more than three-quarters of respondents in both groups said they believed that union agreements "restrict management's ability to redeploy people and redefine job tasks, that "unions discourage individual rewards for the best performing employees," and that "unions provide too much protection for poorly performing employees." The negative numbers were highest at public and private doctoral institutions and at community colleges -- the former where union representation was least common, and the latter where it was most common.

Richard Boris, director of the National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions, at the City University of New York's Hunter College, said he believed the HR directors' responses provided an "accurate snapshot of current attitudes" in higher education, although he suspected that further study might reveal a correlation to the age of respondents, with older HR officers looking more favorably on unions.

He said the results point to a need for "big conversations on most of our campuses where there is unionization, or the climate's going to deteriorate."

Ann Franke, a lawyer and consultant whose career included a 15-year stint at the American Association of University Professors, said she saw the responses as a warning. "Unions would do well to pay attention to their image as protecting poorly performing employees, depriving the most worthy folks from receiving rewards, and limiting transfers," even though "those may be badges of honor for them in protecting their people," she said via e-mail.

Strategists vs. Tacticians

It's hard to find a campus where the chief business officer doesn't belong to the president's cabinet. Same for the admissions director, and the chief information officer. But perhaps confirming the complaint of some HR leaders that they aren't sufficiently valued for their strategic contributions, just over 4 in 10 of the respondents to Inside Higher Ed's survey of chief HR officers said they were officially members of the cabinet at their institution, with a quarter or less at public and private baccalaureate colleges. The outlier was at community colleges, where a full two-thirds (67.9 percent) said they had that status.

More HR directors said they played such a role informally. Nearly six in 10 -- 57.7 percent -- of all respondents said that they considered themselves to be in the president's inner circle and that they were "sought out/listened to for guidance on strategic human resources issues ... as much as you believe is appropriate." The numbers were lowest at public master's institutions (about 40 percent) and highest at private doctoral institutions and community colleges.

Should all of those numbers be higher? Louis Freeh thinks so. The former FBI director -- and the man who investigated the child sex abuse allegations at Pennsylvania State University -- earned many fans in human resources circles when his report on the matter attributed at least some of the university's problems to the fact that its human resources department was left out of the loop. Among his recommendations was that the university upgrade its chief human resources official from an associate vice president reporting to the chief business officer to a VP reporting directly to the president.

Barbara Butterfield, a former HR director at Stanford University and the Universities of Michigan and Pennsylvania who now works for Sibson Consulting, said she agrees with Freeh in principle that HR leaders should be key players in their institutions' decision making, ideally reporting to presidents or provosts. But she said it's not surprising that large numbers of presidents -- by choosing not to put human resources directors in their cabinets -- appear not to see their HR officers that way.

"We're in the middle of a transition [in higher education] between the historic approach of HR as being about transactional employee relations, and the future where it has more to do with problem solving and consulting," Butterfield said. "It's clear that some presidents see their people as more strategic and forward-thinking, and want them on their cabinets, and that others seem to be hired to do transactions, do that well, and stay out of other business."

Casagrande drew a parallel to chief enrollment officers, who at many institutions have been elevated in importance because they are seen as a tuition engine, he said, so their role is directly tied to revenue. "Yet we don't seem to recognize that HR is managing 75 percent of the budget" -- the money tied up in salaries, benefits and employee programs.

Franke, of Wise Results, said no HR officer should report to a president or be on a chancellor's cabinet because of his or her title. "Within the HR field, people who have shown a capacity for issues including workforce planning, faculty/staff employment budgets, and macro ways to address the people needs of an institution would be valuable additions to the cabinet," she said. "But it should be earned."

Though they had slightly different ways of describing it, Franke, Butterfield and Casagrande all agreed about one key trait that HR directors must show to prove that they warrant a key leadership role at a college or university: an understanding and appreciation of the faculty.

"There's a rift between faculty personnel issues and HR in a lot of places, to the point that institutions have personnel positions in their provosts' offices," said Franke. HR directors must show, said Casagrande, that they have the level of emotional intelligence to be able to deal with faculty," just as hospital HR administrators must be able to deal with doctors and those at engineering firms must know that "engineers are the coin of the realm," said Butterfield.

The survey results suggest that many college HR leaders don't see things that way, Butterfield said. "The fact that so few of those surveyed perceived that it’s a problem that senior faculty are failing to retire -- thus inhibiting renewal of the faculty -- suggests that too many HR professionals don't recognize the nature of their institutions."

Added Franke: "If I had one piece of advice to HR people, it's: Don’t complain about faculty; learn to deal with them. Meet them on their turf."

Other Findings

Among other highlights of the survey results:

- Wellness programs are a growing focus. Given a list of issues and asked whether they were paying more or less attention to them than they were five years ago, more respondents (43.4 percent) said they were giving more attention to offering or promoting wellness programs than was true for any other issue. And 73.7 percent agreed that their institution should offer wellness policies that "reward real outcomes" (weight loss, quitting smoking, etc.) rather than just participation in these programs. "That's a good sign, because the only way to manage health care costs is to manage health," said Casagrande.

- Just over half of all respondents said they expected that the Affordable Care Act, when fully implemented, will change their institutions' health care coverage, and about one in six (14.9 percent) said their institutions would realize net savings on their health care costs as a result of the law. Kelly Jones, of Sibson Consulting, said he was not sure enough people are paying attention to complying with the ACA," possibly because of political uncertainty over what the law will ultimately require. "But there are real deadlines that need to be met, and campuses are not immune.”

- More institutions report having health-care coverage and other domestic-partner benefits for same-sex partners (55.2 percent and 49.4 percent, respectively) than for opposite-sex domestic partners (50 percent and 46.9 percent, respectively).

- As has been true for most of the other constituents Inside Higher Ed has surveyed, HR officers conceded that their institutions do not make particularly good use of data. Just 41.1 percent of respondents said they believed their institutions have good data on employee performance, productivity and satisfaction (a high of 51.8 percent at private master's institutions and a low of 28.6 at public doctoral universities) and just 29.3 percent said their colleges made good use of the data they do have.

.JPG)