You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The 2023 Southern African Conference for Artificial Intelligence Research was held in Muldersdrift, South Africa, in December.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Google Deepmind

MULDERSDRIFT, South Africa—The University of Johannesburg might have selected Joburg, rather than the bush, for the most recent Southern African Conference for Artificial Intelligence Research focused on human-centered AI. After all, the city would have offered convenience for attendees from around the continent and beyond. Also, humans are decidedly not at the center of the Gauteng Province’s red-dirt landscape. Here, rhinos, giraffes, hippos, zebras, baboons, antelope, warthogs, ostriches, wildebeests, hyenas and cheetahs rule.

But the Cradle of Humankind—a paleoanthropological site with the world’s largest concentration of human ancestral remains—is a short drive away from Muldersdrift. Hominin fossils found there date back 3.5 million years. On that spot, Homo erectus first used fire one million years ago. Under the sun’s relentless glare, humanity’s long evolutionary timeline feels palpable. Finding a responsible AI path forward for all living things feels urgent.

D'Agostino for Inside Higher Ed

In North America, big tech drives AI, argued Avishkar Bhoopchand, a South African research engineer who works at Google DeepMind in London. In Europe, government policy largely drives AI, he said. But in Africa, the current boom is driven by what many here call “grassroots AI.”

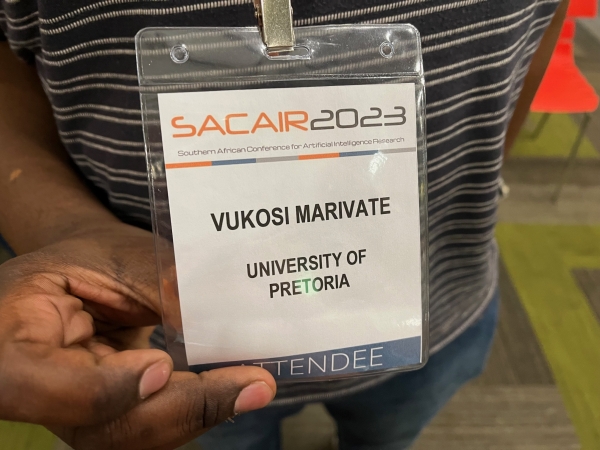

“It’s a broad church,” said Vukosi Marivate, associate professor of computer science and ABSA Chair of Data Science at the University of Pretoria. He was speaking of the self-organized continental network of AI students, professors, researchers, industry practitioners, entrepreneurs and even enthusiasts who offer mutual, homegrown support for accelerating AI in Africa.

Given the perfect storm of too few universities, racial inequities rooted in history, a critical mass of low-income students and a fast-moving global AI landscape that waits for no one, Africa’s grassroots AI movement fills in important gaps.

“We stretch our institutions in multiple ways,” Marivate said. “Anybody can help you at any time. There’s no university, private-sector business or government on this continent that is as far ahead as grassroots AI.”

But what started as a grassroots effort has since attracted attention from global tech companies like Google, Apple and OpenAI. Now, the challenge is to ensure that African AI researchers are, in the words of a prominent gathering on the continent, “not only observers and receivers of the ongoing advances in AI, but active shapers and owners of these technological advances.” The current moment, while fraught, holds significant promise.

Excellent Universities, Many Hurdles

South African universities hold eight of the top 10 spots on Times Higher Education’s rankings of African universities. But the country’s 26 universities can absorb only so many students. With a population of approximately 61 million, that’s one university for every 2.3 million students. That ratio hints at why many here consider university admission on par with winning a lottery.

Among South Africans between the ages of 25 and 64, only 8 percent have earned bachelor’s, master’s or doctoral degrees, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (Only 1 percent earn master’s or doctorates.) In contrast, half of U.S. adults have completed higher education degrees, facilitated by nearly 4,000 American universities. (U.S. universities admittedly have their own concerns; see Inside Higher Ed on any publication day.)

A view of the Upper Campus of the University of Cape Town, seen from the other side of the rugby fields.

Wikipdia Commons/Adrian Frith

“Our universities can’t absorb that many students,” said Marivate, who earned his computer science doctorate at Rutgers University, in New Jersey.

But South Africa’s higher education challenges go beyond available seats. The universities do not serve racial groups in proportions consistent with their presence in the population—a holdover from apartheid. Though South Africa is 80 percent Black, only 16 percent of Black South Africans enter higher education, compared with 55 percent of whites, according to a 2020 report.

“There’s a lot of history, especially with a population that has gone through colonialism,” Marivate said. “People self-organize and say, ‘This is not OK. We need to fix it. We can’t wait for somebody to give us permission to exist.’”

Also, educational inequities begin long before the university setting.

“There are many schools in South Africa that do not offer six school subjects,” said Emma Ruttkamp-Bloem, professor of philosophy at the University of Pretoria and chair of the UNESCO World Commission on the Ethics of Scientific Knowledge and Technology. The phenomenon is more prevalent at majority-Black schools, she added. “What happens at those schools doesn’t translate to what the universities expect.”

Beyond South Africa, though still on the continent, educational opportunities are generally more limited, according to a 2022 Brookings Institution report. Most sub-Saharan African universities lack sufficient computing curricula and manage unreliable and affordable infrastructure, including Wi-Fi and electricity. At the conference venue, the electricity went out a few times each day. Speakers continued without pause or a sound system, signaling familiarity with such episodes.

D'Agostino for Inside Higher Ed

For Africans eager to join the current global AI boom, limited university access and underresourced institutions can pose a problem. Google DeepMind, for example, looks to hire university graduates, according to Bhoopchand.

Those without university degrees “may be able to write fantastic code in circles around university graduates,” Bhoopchand said. “But they don’t have the underlying mathematical or statistical knowledge, which ultimately becomes a limitation.”

Building AI Capacity, One Student at a Time

Most of the students, professors and industry researchers who spoke at the conference hailed from the continent, and some reported on curiosity-driven AI research born from the local setting.

South Africans, for example, speak one or more of one of the country’s 11 official languages—English, Afrikaans, Zulu, Xhosa and seven others. Several of the established and rising computer scientists presented research on augmenting AI data for low-resource languages.

D'Agostino for Inside Higher Ed

Many sought to foster human flourishing, citing uses of AI that include misinformation detection, reducing poverty, diagnosing lung cancer and pursuing intergenerational justice, as a driver for responsible AI. One researcher addressed the potential for unregulated, lethal autonomous weapons to undermine human rights and global stability.

“We need to show up in our relationship with the West as equals,” Bhoopchand said. “Not one in which the West sees us as a charity case—or, worse, as a testing ground for their technology or one in which they can exploit or extract resources from Africa.”

Bhoopchand’s concern is grounded in a dark reality. In 2021 and 2022, for example, OpenAI—a U.S. company—contracted Kenyans (through a third party) to work as content moderators training ChatGPT. The workers reviewed texts and images, including those “depicting scenes of violence, self-harm, murder, rape, necrophilia, child abuse, bestiality and incest,” according to The Guardian. Many of the workers, who were paid between $1.46 and $3.74 an hour, were traumatized—and later fired.

“Because of the geopolitics, we can’t walk,” Marivate said. “We have to sprint.”

The Rise of ‘Grassroots AI’

The higher education community here has had to grapple with what Marivate called “the lived reality of the South African student.” Since 2018, the government has offered free university tuition and a living stipend to university students whose families earn under 350,000 rands (approximately $19,000). Most South Africans (90 percent) qualify for this National Student Financial Aid Scheme, according to the World Bank. But that has had unintended outcomes.

“For a lot of kids, getting that stipend makes them the breadwinner at home,” Marivate said, adding that acquiring high-level AI research skills takes four or more years. “It’s very hard for them to stay an extra year or two for a master’s degree. Now imagine asking them to do a Ph.D.” Those with AI skills can earn far more in industry than as students or faculty in academe.

Wikipedia/Mike-Prins/CC BY-SA 3.0

“My colleague in statistics has classes with 1,000 students,” Marivate said. “Then people quit, and it becomes crazier.”

Students who clear the access and financial hurdles sometimes discover that their institutions offer insufficient resources and faculty expertise to support their AI interests. That’s where grassroots AI offers a vital assist. A faculty member on the front line identifies resources or experts at another university, nonprofit or private business somewhere else in the country or continent—anything to ensure the student stays on an AI research path.

Marivate’s mental map of Africa, for example, appears to be overlaid with the names of individuals and institutions from academe and beyond that can support AI students in need. Tanzanians in AI, he offered as an example, are “very entrepreneurial” and can often offer expertise on building and scaling electronics in AI start-ups. Ugandans have specific strengths in AI for the internet of things, he said. If a Sudanese student needs help with a machine learning project or a Kenyan student needs help with AI for data science, Marivate and others stand ready to foster continental connections. Though Marivate is based at Pretoria, he advises AI graduate students studying at universities across the continent.

Grassroots AI—as a term and a phenomenon—was an open secret at the conference. Two South African computer scientists employed in industry, for example, mentioned serving as the primary dissertation advisers for several African computer science doctoral students focused on AI. The individuals, who asked not to be named given the nontraditional arrangement, acknowledged that both the universities and their employers are aware of their substantial—but uncompensated—work guiding African AI students toward degree completion.

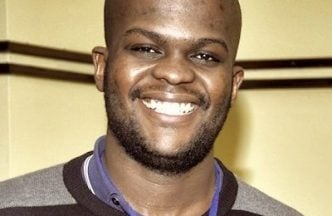

Benjamin Sturgeon, a master’s student at the University of Cape Town, is interested in adding moral reasoning to machine learning agents.

Susan D'Agostino for Inside Higher Ed

“I had to create this niche for myself,” Sturgeon said of his research interests at the intersection of computer science and philosophy. In South Africa, “there’s a sense that [AI ethics] is not our problem, that people in the first world are working on it.”

In short, grassroots AI seeks to create a bubble in which computer science students can focus on their research.

“If we don’t, only very privileged people make the choice to spend three, four or five more years” preparing to lead in AI, Marivate said. “This grassroots thing is important. It heals and removes bumps so that people can just be.”

But intracontinental networking on behalf of one student at a time can feel isolating. To see, feel and benefit from the macro view, many here head to the Indaba.

Indaba

Less than a decade ago, Marivate and colleagues imagined an indaba—Zulu for “gathering”—in which emerging and established African AI researchers could come together to listen, share news, discuss community interests and concerns, and mentor each other. They realized their dream in 2017 with the first annual Deep Learning Indaba conference. The community’s mission is “to strengthen machine learning and artificial intelligence in Africa by building communities, creating leadership, and recognizing the research and application excellence of African innovators.” What began with a few attendees now engages more than 3,000 people every year.

AI Expo Africa

Conference participants in Muldersdrift dropped frequent, glowing references to the weeklong Indaba conference and the IndabaXes—one-day Indaba-like events held in local African communities. But the grassroots gatherings still have some bugs to fix.

“I left IndabaX [in Cape Town] with a broken heart because this Ph.D. student in health care was trying to do [AI in medicine], and she had no access to medical data,” Eleanor Kedem, a computer science master’s student at the University of Cape Town, said. “The researchers were looking for collaborations that were very hard to find—both in terms of data and in terms of technologies.”

Nonetheless, many Africans credit Deep Learning Indaba—or Indaba, for short—with putting homegrown African AI on the global AI map. Marivate recalls when the organizers secured Jeff Dean, Google’s chief scientist focused on AI, to speak at the 2018 Indaba.

“Dean spent four days at Indaba, and he was like, ‘What?!’” Marivate said, widening his eyes in an imitation of Dean. Soon after, Dean announced that Google would open its first AI research center in Africa. Importantly, he referenced Indaba in the announcement.

“We’ve seen people across Africa do amazing things with the internet and technology—for themselves, their communities and the world,” Dean wrote at the time. “AI has great potential to positively impact the world, and more so if the world is well represented in the development of new AI technologies.”

‘Think Bigger—Much Bigger’

Marivate’s uplifting, if at times chaotic, vision for how African researchers will rise to this global AI moment was on full display in Muldersdrift. His conversations were often interrupted, and his talk was delayed as he fielded calls from foreign ministers and tech leaders wanting to discuss funding for African AI research.

“I’m at peace with my role as an AI politician,” he told the packed room upon arriving late to his talk, sliding his cellphone into his pocket and launching into a discussion of natural language processing for Setswana, a low-resourced language. This, apparently, was a normal day for him.

D'Agostino for Inside Higher Ed

In 2023, the United Kingdom announced plans to invest 80 million pounds (approximately $102 million) to “support home-grown AI expertise and computing power in Africa and help the continent’s AI innovators boost growth and support the continent’s long-term development.” The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is set to invest $30 million in “an AI platform in Africa that will provide African scientists and innovators with technical and operational support to turn ideas into scalable health and development solutions.”

By 2050, one in four people in the world will be African, according to a New York Times report. The continent’s population is expected to nearly double to 2.5 billion in the next quarter century, while birth rates in wealthier nations are expected to tumble. At the same time, Africa lags behind much of the world in AI, according to an index by Oxford Insights, a U.K.-based consultancy. Mauritius, the highest-ranked African country on this government-readiness index, ranks 57th globally. South Africa, the second-highest African country, ranks 68th.

But some foreign governments and big tech funders view Africa’s allegedly low AI readiness as an AI opportunity.

“There are other projects [beyond the U.K. and Gates Foundation investments] I cannot talk about,” Marivate told attendees. “There is a ridiculous amount of funding that is about to come … You’re not thinking big enough. Think bigger—much bigger.”

The message was clear: Africans need to build AI research capacity fast, lest they are left behind. But they also need to shape their own AI path.

Susan D'Agostino for Inside Higher Ed

Funders often seek assurance that recipients are poised to use donations within a short time span. That can sometimes present hurdles when an institution is starting from scratch in a given area. For African computer scientists who are unable to accept funding offers, Marivate offered direct, candid advice.

“Refer,” Marivate told the packed conference room. “Get the funds. Completely break that thing of saying, ‘No, because I can’t do it, it can’t be done.’ There are other people on the continent.”

Later, a source stopped this technology correspondent in the hallway. The source expressed thanks for having listened to her and others at the conference. In response, I expressed gratitude that attendees were willing to share. I had learned a lot, I told her, and anticipated using many of the quotes in a story. But the source was not concerned about publication.

“Someone, somewhere, thought it was important for you to come to Africa and listen to us,” she said. “Thank you for that, regardless of whether you publish a story.”

Roadside fruit stand on the road between Muldersdrift and Johannesburg.

Susan D'Agostino for Inside Higher Ed

On the road back to O. R. Tambo International Airport in Johannesburg, fruit stands overflow with watermelons and billboards advertise the likes of Galaxy Z flip phones. A lot has transpired in science since Homo erectus discovered fire.

Wildebeest and zebras crossing the Masai River during the great migration in Serengeti National Park, Tanzania.

Getty Images/nikpal

But the roadside herds of grazing zebras and wildebeests mirror the collaborative spirit of emerging and established African AI researchers amid the current tech boom.

Wildebeests, who can smell rain miles away, help zebras find water. Zebras, who have excellent eyesight, help wildebeests spot predators. Zebras also feed on the top of grasses, while wildebeests prefer the lower parts, ensuring they both thrive without competing for resources. By traveling side by side in a symbiotic relationship, they also find strength in numbers against predators.

“It’s not for us [Africans] to win the AI race,” Marivate said, confiding that he’s heard from senior researchers at world universities who were surprised to learn that South Africa has roads. “It’s for us to be counted.”