You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

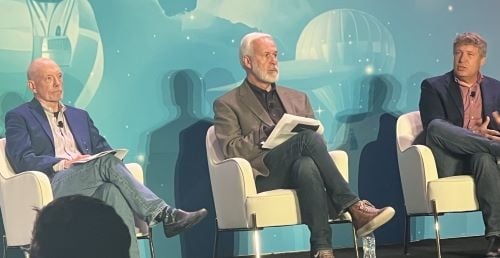

Ted Mitchell of the American Council on Education, Paul LeBlanc of Southern New Hampshire, and George Siemens of the University of South Australia, at this week’s ASU+GSV Summit

X

In an era of generative artificial intelligence (AI), data is king. The large language models on which AI tools are built depend on enormous volumes of data, training and managing AI tools requires powerful (and often expensive) computing power, and major tech providers are far ahead of everyone else in driving AI forward. That creates potential threats for everyone else.

A group of higher education leaders are joining forces to try to make sure colleges and universities—especially under-resourced ones—aren’t left behind as generative artificial intelligence transforms our work and our lives.

The American Council on Education (ACE) is leading the effort to establish the Global Data Consortium, through which participating colleges, nonprofit groups and others around the world would contribute institution-level datasets on learners to create an enormous body of information. Researchers, institutional leaders and, potentially, companies could tap into the consortium to build AI products and develop their understanding of what works (and doesn’t) in the student journey.

“The way higher education shapes its own future is by owning our data,” said Ted Mitchell, ACE’s president.

Officials at ACE and its partners emphasized that the envisioned technology that would be used to build the network (which involves the use of “synthetic datasets”—artificial constructs engineered to mimic the statistical properties of real-world data without compromising individual privacy—and “meshing”) would allow participants to glean insights from the data without actually giving them access to the underlying student information, which would remain firmly under the control of the participating colleges.

Paul LeBlanc, the departing president of Southern New Hampshire University who is focusing on artificial intelligence in the next act of his career, said that enough major institutions, governments and others have committed to the project that the database would already “have data on 35 million students the day we turn it on.”

“We seem to be overcoming the idea that your data is your [institution’s] competitive advantage,” LeBlanc said. “Right now we are having to be very reactive—what is Open AI making, how might we use that?”

Collaborating, he added, is higher education’s best chance to “own our own future” rather than let Google, Meta, Amazon and other major technology powers control the AI landscape.

This is especially important, said Scott Durand, a former Southern New Hampshire official who is overseeing the project for ACE, for “small and under-resourced institutions that would have the hardest time playing in the AI game.”

Major universities like Arizona State and the University of Michigan have struck agreements to collaborate with Open AI, and other major universities are creating their own AI tools, but not all institutions have the resources to do that well.

Colleges that don’t have significant institutional research offices could glean insights into how their own student bodies compare to learners at other institutions and benefit from AI tools the consortium’s members develop together. Durand also said the consortium envisioned providing technical support to needier colleges and universities.

College officials briefed on the project expressed excitement but acknowledged potential hurdles.

Dan Greenstein, chancellor of the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education, saw the potential for an “accelerated pace of innovation” through this sort of data-sharing and collaboration.

“We may be able to help people avoid going down blind alleys or replicating work others have already done,” he said.

But he emphasized that participating institutions would have to meet a high bar for ensuring the quality of the data they contribute and to agree to abide by the restrictions the consortium sets on how the data are used. “Membership has certain obligations,” he said.

“Data will be shared on a solution-oriented basis,” states a technical white paper about the project co-written by George Siemens, professor and director of the Centre for Change and Complexity in Learning at the University of South Australia. “This means that data is shared as it relates to a consortia project or to a particular capability that members want to realize. This ensures that data made available addresses a clear need, rather than sharing for the sake of sharing.”

The consortium is in discussions with leading foundations about initial funding, and the effort could ultimately be funded through membership fees, fees for access to the data or other methods.

Institutions interested in learning more can sign up for updates here.