You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

People watch the solar eclipse at Saluki Stadium on the campus of Southern Illinois University on August 21, 2017 in Carbondale, Illinois.

Getty Images/Scott Olsen

On April 8, a total solar eclipse will pass over the United States, prompting teams of physicists and astronomers to take the spotlight normally reserved for star quarterbacks in college stadiums around the country. Concession stands will serve Moon Pies, Sun Chips, Milky Ways, Mars Bars, Sunkist lemonade, Starry soda, and Eclipse and Orbit chewing gum.

Sound systems will blare Bill Withers’ “Ain’t No Sunshine,” the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun,” and the Rolling Stones’ “Paint It Black.” Students, faculty and staff will distribute protective eyewear, oversee public access to astronomical equipment and facilitate citizen science projects. Security—enhanced for the day—will direct traffic, monitor walk-through metal detectors and screen bags for weapons.

“We approached it as a major football game,” Michael Johnson, chief marketing and communications officer at Texas A&M University–Commerce, said of this astronomical event for which the university did not otherwise have a playbook.

The mood on campuses around the country should be festive, if eerie. Birds may stop singing. Spiders may dismantle their webs, and nocturnal bats may emerge from daytime roosts. In the United States, the moon will first block the sun in Texas before doing the same in Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois, Kentucky, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine. That puts an estimated hundreds of higher ed institutions along the path of totality.

Many colleges will serve as ground zero for public eclipse watch parties in their regions, with most eyes on physicists—and, briefly, the sky. Higher ed institutions have spent years planning for April 8, including by optimizing strategies for safety and access. The programming aspires to instill awe, enhance public science literacy and foster community both on and off campus.

But a lot could go wrong. Crowds could overwhelm some campuses. Medical supplies, fuel, food and water could run short. Also, the potential for less-than-ideal weather has many holding their collective breath.

“My biggest worry is clouds,” said Aileen O’Donoghue, the Henry Priest Professor of Physics at St. Lawrence University, in northern New York. “I really, really, really, really, really want to see the corona,” referring to the hot, ionized gas or “ring of fire” that is expected to surround the moon during totality.

O’Donoghue had tried to see a total solar eclipse in Kansas in 2017, but clouds got in the way. Should the same happen this year, she has contingency plans. Australia will experience total eclipses in 2028, 2030, 2037 and 2038; she’ll go to as many as necessary in the hope of viewing at least one totality.

“Ninety-nine percent of totality is as different from totality as day is from night,” O’Donoghue said, echoing a sentiment expressed by many other physicists with whom Inside Higher Ed spoke. “At 99.9 percent of totality, it’s still daytime. You don’t get night until the entire sun is covered.”

Baily's Beads (also known as a "diamond ring") appear as the Moon makes its final move over the Sun during the total solar eclipse.

Munizaga/Wikipedia

Indeed, physicists speak of totality much in the way football fans speak of winning Super Bowls. Only totality reveals visible stars and planets. Only totality produces Baily’s beads (a “necklace” of light “beads” around the moon from sunlight interacting with the moon’s uneven surface) and shadow bands (wavy stripes of light and dark on solid-colored surfaces), according to LiveScience. Also, only those in the path of totality will see the rarely seen sun’s corona.

But for this rare celestial event, colleges have also adopted a robust, American-style consumerism. They will distribute and sell heaps of “must-have” college-branded eclipse merchandise. This includes T-shirts (some glow in the dark), stickers, keepsake guidebooks, picnic blankets, buttons, cups, photo-booth style pictures of friends superimposed with an eclipse image, and party kits that include “eclipse glasses, sunscreen, a reusable water bottle, educational materials, and lots of fun swag,” in a university-branded tote bag.

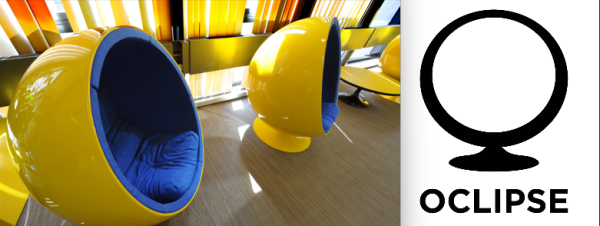

Though the natural phenomenon transcends institutional and political boundaries, some colleges have claimed pieces of it as their own. St. Lawrence University, for example, has dubbed itself the “Gateway to the Path of Totality.” (Those who agree may commemorate the sentiment with a hoodie.) Oberlin College has rebranded the celestial event “Oclipse,” which includes a logo inspired by their library’s moon-like “womb chairs.” Dallas College has labeled the phenomenon the “Big D Eclipse.” The University of Texas invites visitors to experience the “UTotal” phenomenon “the Longhorn way!”

Oberlin College has rebranded the celestial event “Oclipse,” which includes a logo inspired by their library’s moon-like “womb chairs.”

Oberlin College and Conservatory

Next week will also bring a wave of solar eclipse closures at colleges around the country. At the same time, remote learning options mean that students and instructors who elect to view the eclipse may be held accountable for learning that otherwise might have occurred. The University at Buffalo, for example, has canceled in-person classes on April 8, citing an expected “more than one million visitors to the Buffalo region.” But the institution has encouraged instructors to offer remote instruction with asynchronous options for students who cannot attend in real time. (Inside Higher Ed anticipates a smattering of opinion pieces in defense of “total eclipse days,” analogous to “Let Snow Days Be Snow Days.”)

Some colleges have opted to cancel class for a few hours on the day of the eclipse. Gannon University, for example, will close from 1:20 p.m. to 4:30 p.m., and the University of Dayton will cancel class from 1:25 p.m. to 4:50 p.m.

Other university class cancellations are generous. Indiana University, for example, has canceled classes on all campuses throughout the state for the entire day—with no mention of make-up work—to “ensure that as many of our IU community members as possible can experience the eclipse.”

Spider and total solar eclipse with diamond ring effect.

kdshutterman/Getty Images

Those at colleges whose colors are red or green may witness an enhanced Purkinje effect in which, minutes before the totality, color saturation may appear off. Reds will darken, and greens will brighten in “otherworldly” ways. Wildlife reactions, changing winds, and scrambled radio waves may also be more pronounced during totality. But community members at Duke University, whose main color is a shade of navy blue, may hesitate to wear the red of their rivals at North Carolina State University (especially after Sunday’s NCAA tournament game).

For many physicists, the eclipse also presents a welcome opportunity to depoliticize science.

The corona of the sun visible around the moon during a total solar eclipse.

Space Frontiers/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

“I was not happy with a lot of the way science was presented during the pandemic. People tried to use it to push agendas,” said David Donovan, professor of physics and department head of physics at Northern Michigan University. With the eclipse, “you see something neat, and it doesn’t matter what your politics are.”

In anticipation of April’s total solar eclipse, Inside Higher Ed offers a Harper’s Index-like statistical poem for physics and astronomy teachers and students around the country. Many have spent years preparing for this minutes-long, community-minded event that, in large part, relies on clear skies.

A Statistical Ode to Physicists Before the Solar Eclipse

Number of total eclipses Rice University professor of astronomy and “eclipse junkie” Patricia Reiff has seen: 17

Number of total solar eclipses University of Arizona emeritus professor of astronomy Glenn Schneider has seen: 33

Number of public guests Indiana University is prepared to host during the April 2024 total solar eclipse: 52,626

Number who should experience the eclipse as a spectacle, according to Navajo culture: 0

Number of tribal colleges and universities in the path of totality: 0

Historical average cloud cover on April 8 at the University of Texas, San Antonio: 54%

Historical average cloud cover on April 8 at the University of Maine, Presque Isle: 80%

Height in feet of the University of Maine, Presque Isle’s 3-D sun model to be unveiled on the day of the eclipse: 23

Number of free protective glasses the University of Arkansas at Little Rock plans to distribute: 30,000

Number of seconds during which a glance at the sun without proper eye protection is safe: 0

Cost of university-branded eclipse glasses at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: $0.50

Cost of such “shades” at Ohio State University: $5

Number of years Southern Illinois University has had an eclipse steering committee: 9

Number of members in the State University of New York at Plattsburgh’s Eclipse 2024 Steering Committee: 24

Number of Texas counties that have issued disaster declarations ahead of the eclipse: At least 7

Number of expected visitors to Central Texas College, whose county has preemptively declared a disaster: 320,000

Number of enrolled students at White Mountain Community College in Coos County, N.H.: 617

Number of expected visitors to Coos County, N.H., during April’s eclipse: 50,000

Rank of the month of April in New Hampshire’s mud season, when many roads are impassable during the day: 1

Number of opinion articles in The Colgate Maroon-News arguing that class should be canceled because “the eclipse fits in with—and even transcends—the goals of a Colgate education.”: 1

Number of opinion articles in The Middlebury Campus arguing class should be canceled “to maximize our collective experience of this rare event.”: 1

Percentage of people with less than a high school degree who say that the benefits of scientific research outweigh the harmful results: 52

Percentage with a bachelor’s degree who say the same: 84

Percent increase in cannabis sales at some Oregon dispensaries prior to the 2017 solar eclipse: 500

Number of college spokespeople (out of six) who acknowledged concern about a potential rise in student cannabis use during the eclipse: 0

Cost in dollars of a university-branded eclipse T-shirt at Hendrix College in Arkansas: 17

Number of porta-potties planned for Hillsboro, Tex., home of Hill College, during the eclipse: 200

Years since Kenyon College in Ohio has been in the path of totality: 218

Years since Southern Illinois University has been in the path of totality: 7

Number of Nationwide Eclipse Ballooning Project participating institutions across the path of totality: 75

Percentage of those institutions that are minority-serving: More than 30

Percentage that are community colleges: 15

Number of tactile 2024 eclipse books astronomers at the College of Charleston, Pennsylvania Western University, and NASA distributed for low-vision individuals: 11,000

Number of physics and astronomy degrees awarded at U.S. institutions in 2021: 13,674

Number of astronomy Ph.D.s awarded in 2021: 171

Median annual wage for astronomers: $128,330

Length of time the April 2024 total solar eclipse will take to cross the United States: 68 minutes

Duration of totality in minutes at Southeast Missouri State University: 4 minutes, 6 seconds

Duration of totality in minutes at the University of Akron, in Ohio: 2 minutes, 48 seconds

Percentage of people in the United States and Canada who may experience a partial eclipse on April 8: 100

Percentage of North Americans who may experience totality: Less than 1

Number of other planets in the solar system that experience total solar eclipses: 0

Number of years from now after which Earth’s total solar eclipses will cease: A few hundred million

Number of minutes Clemson University adjunct professor of physics and astronomy Donald Liebenberg spent in the path of totality of a 1973 eclipse aboard the Concorde supersonic jet: 74

The Concorde supersonic plane, circa 1969.

Andre Cros/Wikipedia