You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

What does the exchange of ideas across our Inside Higher Ed community look like without comments?

As you know, the leadership of Inside Higher Ed decided to eliminate commenting and replace comments with letters to the editor. At the time of this decision, I wondered if some of the conversations about Inside Higher Ed news and opinion pieces that had previously occurred in the comments would migrate to Twitter?

In responding to that question (in comments), many of you were skeptical about the utility of tweets as a means of dialogue and exchange. Some examples:

"Twitter does not encourage constructive discussion." (MarkRoulo)

"I have a Twitter account but I would never use it for the purposes we are discussing here. Twitter is definitely not structured for such conversations. Besides, being academics, we often need more than 240 characters to express our thoughts. Further, it doesn't the threaded architecture that is called for." (murliman)

"Twitter is awful. Its threading is awful. Its readability is awful. Its character limit is awful. Its community is awful. Everything about it is awful." (Unemployed_Northeastern)

"The community on Twitter can be awful. But that's what the block function is for." (Elaine Vincent)

"So, ah, where can this group go? You are closer to the technology. Is Twitter the only option? Yuck." (Glen_S_McGhee_FHEAP)

This week, we have had the opportunity to watch a small natural experiment unfold regarding responses by tweets and replies by letters to the editor.

On July 6, I published a piece titled "Where 'Generals Die in Bed' Gets Online Education Wrong." My blog post was a response to Jeff Kolnick's Views article, "Generals Die in Bed."

My blog post generated a number of both letters to the editor (which were published), and tweets.

The letters to the editor included:

- Kim Versus the Generals by Glen S. McGhee, director, Florida Higher Education Accountability Project

- Why Normal Arguments for Online Education Don't Apply Right Now by Ron Giordano, college parent

- Criticizing Without the Facts by Donald F. Larsson, Ph.D. emeritus professor, Minnesota State University, Mankato

What is fascinating is how the letters and the tweets differed. Almost universally, the letters were critical of my piece, and the tweets were positive. Why might this be so?

I can make some guesses, but this little unintended experiment in letters vs. tweets has gotten me thinking that we need a theory of academic social media. Or maybe a theory of social media in general.

Without a theoretical framework to understand the structure, value and meaning of social media exchange, we will find it challenging to build testable hypotheses.

Why do tweets in responses to articles or opinion pieces tend to skew more positive?

I'd say the answer is twofold: connectivity and reputation.

The Twitter connectivity argument for positive skewing tweets likely has the most explanatory value. Those who follow me at @joshmkim are people in my network. I'm connected to them, and they to me. We are likely to be more favorable to those in our network.

By reputation, I'm thinking of the importance of the tweeter's reputation and the impact of that reputation on subsequent tweets.

The first person to tweet about my article was @PhilOnEdTech. Phil, who is widely respected (and followed by over 7,770 of us), likely set of a cascade of positive reactions. (Disclosure: Phil is a friend -- and a colleague that Eddie Maloney and I wrote about in our recently released book, Learning Innovation and the Future of Higher Education).

Phil tweeted:

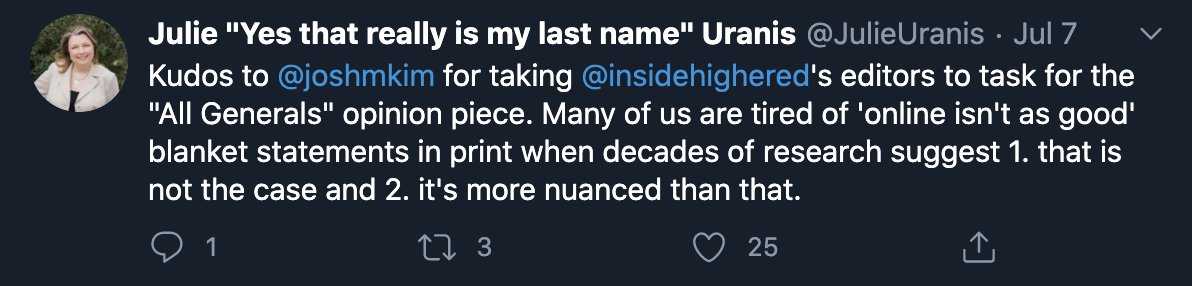

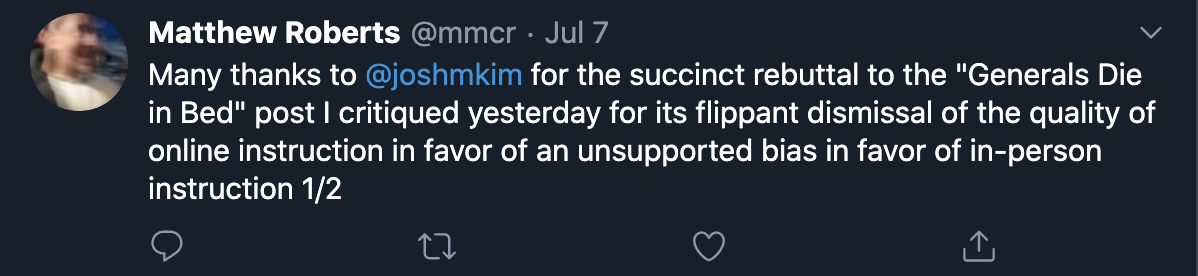

Following Phil's tweet were a series of other positive tweets about my article, some of which I'll reproduce here:

What to make of all this?

The critical letters to the editor were well reasoned, collegial and persuasive. A letter to the editor seems to give space to build an argument and engage in a respectful discussion.

It may be that letters to the editor are more likely to be critical, as why take the time to craft a letter if all you are doing is agreeing with the original article or opinion piece?

Alternatively, the barriers to tweeting are low. It is a simple matter to signal alliance, support and solidarity in a tweet.

Tweets are less about persuasion and more about signaling. Tweets are read by followers within your network. Letters to the editor can be read by everyone.

What neither tweets nor letters to the editor provide is a space for conversation. The structure and format of Twitter is suboptimal for collegial conversation across people who disagree with one another.

Twitter might be better for talking than it is for listening. Or at least the sort of listening we need to do when we disagree with what the speaker has to say.

It is a shame that our Inside Higher Ed community could not find a way to make comments a force for collegial exchange, debate and listening.

Thank you to everyone who took the time to write, tweet and read. Your time and attention are all hugely valuable, and your perspectives and expertise are appreciated.