You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

How the World Became Rich: The Historical Origins of Economic Growth by Mark Koyama and Jared Rubin

How the World Became Rich: The Historical Origins of Economic Growth by Mark Koyama and Jared Rubin

Published in May 2022

The core questions at the heart of much of the social sciences are about inequality. Why are some people poor and others rich? Why are some countries low income and others high income? When, if ever, will the people living in currently low-income countries transition to middle and high income? Why did some parts of the world become rich when they did, ahead of everyone else? What determines if a country is rich or poor?

How the World Became Rich ignores the first question about individual wealth and poverty, instead taking the country (or region) as the unit of analysis. The book aims to synthesize the major theories on comparative national economic development and then bring these theories into conversation with one another.

In these days of doom and gloom (climate change, erosion of democracy, rising economic inequality, etc.), it is good to remind ourselves just how fortunate we are to be born when we were. Some of the historical economic data cited in How the World Became Rich is from the site Our World In Data, so I thought we’d start there.

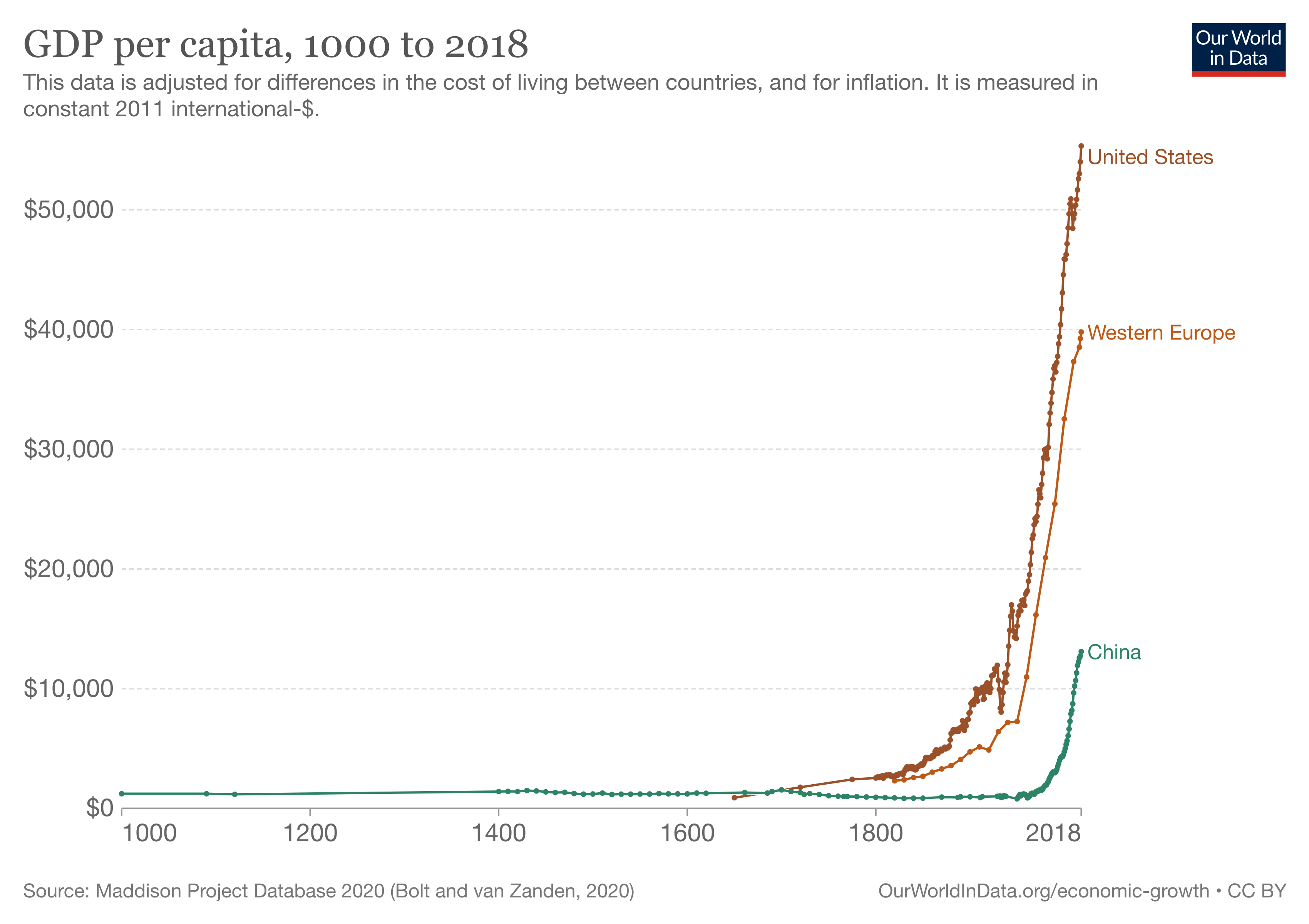

The graph below shows GDP per capita (in constant 2011 dollars) from 1000 to 2018 for China, the U.S. and Western Europe.

Three things are immediately apparent:

- GDP per capita was extremely low and highly stable for most of the centuries from 1000 on.

- The slope of the GDP per capita line is exceptionally steep, with income per person rising sharply in Western Europe and the U.S. both in the 19th and 20th centuries and in China late in the 20th.

- While China’s rise from poverty to middle-income status has been rapid, the country is still relatively poor on a per-capita basis compared to the West.

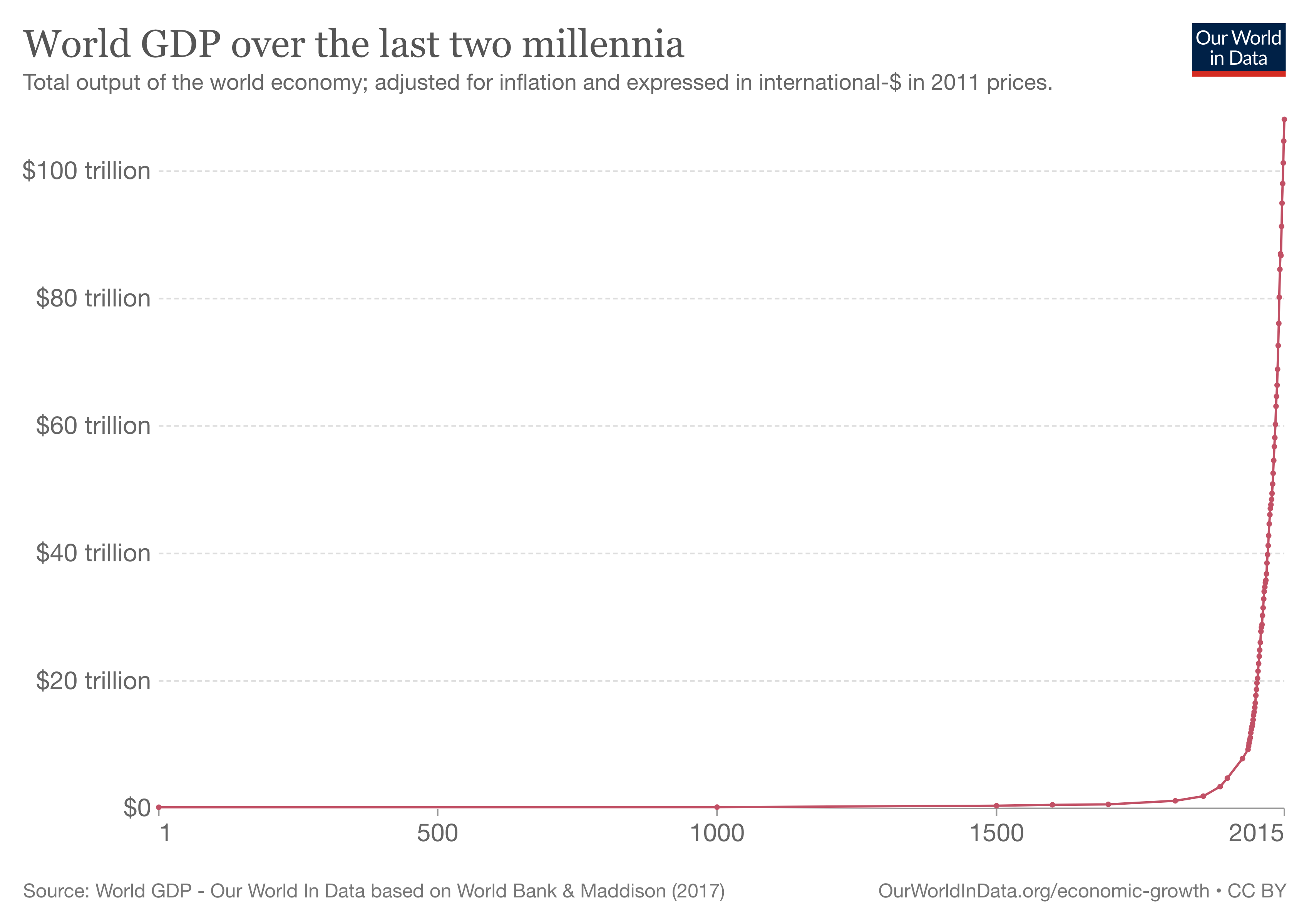

Another way to visualize the story of wealth is to look at the change in the total value of all goods and services, the world GDP, over the past couple of thousand years. The graph below starts in year 1 and takes us to 2015. Almost all the accumulation of world wealth has occurred in the last two hundred years, with most of that change coming in the previous 50.

So why was it that the world was always poor and suddenly became rich?

How the World Became Rich traverses the major theories to answer this question while leaving out one.

Theories of differentials in comparative national economic development include geography, institutions, culture, demography and colonization. Universities are the one theory not considered in this otherwise comprehensive, fair-minded and balanced synthesis of global economic history.

Why should we consider the development of an ecosystem of universities as the cause, rather than the effect, of the rise of global wealth?

The preferred explanation of Koyama and Rubin for how the world became rich is institutions. Institutions enable a stable foundation for the technological progress that drives the productivity gains on which economic growth depends. When the authors of How the World Became Rich talk about institutions, they speak broadly of the systems of government, law, political economy, education and market structures in which economic life is embedded.

Might the ideas of what constitutes good institutions come from thinkers based at universities?

Would liberal democracies exist in the absence of institutions of higher education?

Even if you don’t believe that ideas drive the world (I do) and that the great incubator of ideas is universities, you might concede that productivity gains require innovation. An incomplete list of innovations that came from university research (almost always funded by government dollars) includes:

- Telescopes

- Radio

- Television

- Computers

- The internet

- Web browsers

- Programming languages

- Computer games

- Spreadsheets

- Hypertext

- LCD screens

- LEDs

- Plasma screens

- Touchscreens

- E-ink

- GPS

- Lithium-ion batteries

- Lasers

- Electron microscope

- Solar power

- Nuclear power

- Insulin

- Antibiotics

- Chemotherapy

- Ultrasound

- MRI

- X-ray

- Fluoride toothpaste

The authors of How the World Became Rich make a strong case for the interaction of demographics and culture, geography and colonialism, in shaping the institutions that determine differential national economic development. Any reader interested in understanding the reasons behind the graphs above will gain enormous insight by investing time in reading this book.

At the imaginary dinner party that I’m conjuring with Koyama and Rubin, I’d press them on my hypothesis that universities are as much the source as the beneficiary of national economic growth.

What are you reading?