You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

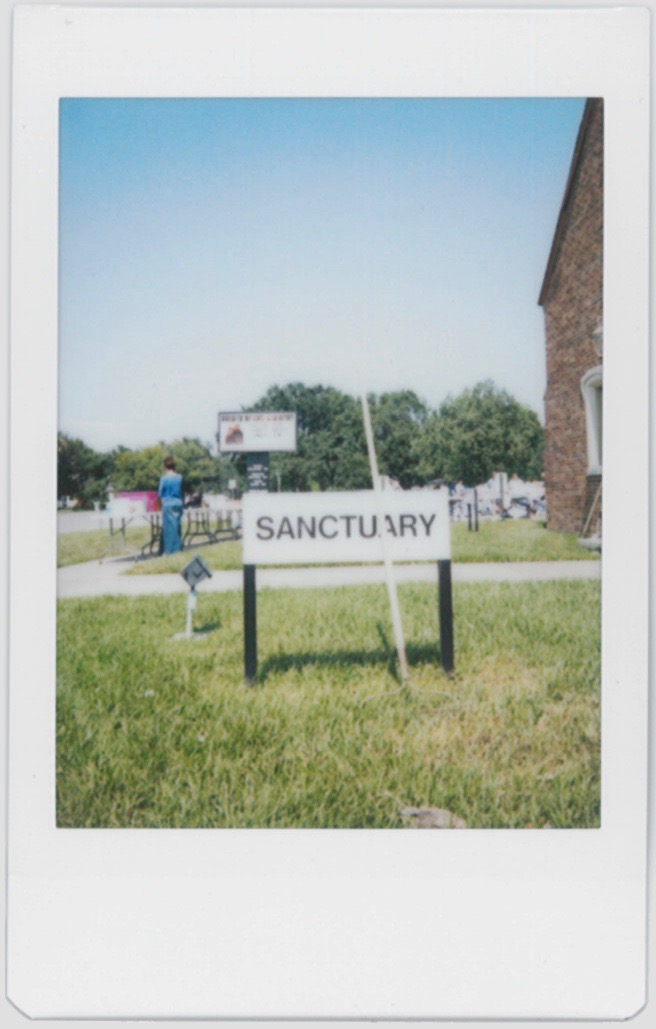

There is something inherently warm about a Polaroid photo. Maybe it’s the saturation of color in the print, the vividness of a moment we can hold in a square in our hands. Maybe it’s the camera’s non-critical eye, which can make even the most unphotogenic of us look like part-time models. Or maybe its warmth lies in its impermanence, the delicacy of the photograph invoking our sense of mortality in an age in which a photo can live in relative eternity, on social media or in the cloud. The format has the ability to bring out the most nostalgic side in all of us, a nostalgia that can put a rosy finish on an imperfect pose and obscure the darker shades of a particular moment in time.

I drove across the Louisiana border into east Texas, where Hurricane Harvey had passed just a few days before. There, I found shoes drying on doorsteps, rolled-up carpets on the curb, cars with doors spread open, trucks floating in still-flooded neighborhoods, people assessing what they could dry out, what they could salvage from the storm. I wanted to document what had happened, what was still happening, but I didn’t want to create another cell phone photo, the type of image that could easily become submerged on your social media feed.

For some, there is a desire to forget this disaster, to ignore the news articles shouting THIS IS CLIMATE CHANGE, to keep drilling the swamps and await the next cataclysm. Digital photographs of the flooded streets will eventually drift to the bottom of the news feed. On to the next disaster...

When you take a Polaroid, you take a part of the moment with you, literally: the light that bounces off of the subject gets imprinted in the photo itself. With a Polaroid, a moment cannot be easily scrubbed from memory. With a Polaroid, you have to take it with you. You can place it at the bottom of a drawer, hope to forget, but you will still feel it beating there, a heart under the floorboards.

There is something inherently warm about a Polaroid. These are not happy photos, though when you look initially it may seem that way. Sometimes, the easiest way to take your medicine is by masking its bitter taste in a gummy candy, to realize the harshness of our new reality through the comforts of a familiar white frame. You can put the Polaroid on your fridge, next to your friend’s engagement photo, and say, This too is reality. This disaster should not be forgotten. This act of devastation is not fake news. This is what the lives of our neighbors, students, friends look like now.

These photos were taken in two Texas cities, Port Arthur and Bridge City, days after Harvey struck.

***

Lee Matalone writes a column on death, loss and mourning for The Rumpus. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Joyland, Nat. Brut and the Heavy Feather Review.