You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

In January 2014, HASTAC, the nonprofit open learning network we founded in 2002 and now 12,000+ network members strong, will be mounting an international #FutureEd initiative designed to inspire thousands of students and professors to think together in innovative ways about the “History and Future of Higher Education.”

In times of tremendous social and political change, such as during the Industrial Age—especially in those eras where radical new technologies rearrange the conditions of labor and the connections between areas of knowledge—education often is the means by which a new generation can be prepared for the challenges ahead.

Oddly, in the current era, the Internet has changed our world faster and more extensively than anything we’ve ever seen before. But the biggest drivers to change have come from outside rather than inside higher education. And not necessarily in a good way.

Legislatures incongruously slash public funding to education right when more, not less, investment in public education is necessary. At the same time, venture capitalists are clamoring to MOOCs. It's not clear if that is from a desire to find the best ways to promote future learning or merely done with the hope of short-term profits.

Our #FutureEd Initiative is based on the idea that higher education today needs serious transformation, and that innovation should be led by the most serious stakeholders in higher education: namely, students and professors.

Let me be clear: I am not pro- or anti-MOOC.

In fact, as part of this initiative, I’ll be teaching a MOOC on “The History and Future of (Mostly) Higher Education.” I’m doing this for many reasons, chiefly wanting to learn what, if anything, we can learn about learning from this form.

(Spoiler alert: my preliminary intuition is that the business and learning models of this generation of MOOCs are too crude to pose a serious threat to higher ed nor will they magically bring down costs.)

But I do think MOOCs have the potential to expand access to education to many who are normally excluded (for reasons of funds, location, work or family life, prerequisites or physical or cognitive abilities). And it is exciting to include this “massive” community in our thinking about the purpose and design of higher education.

#FutureEd isn’t just a MOOC. It’s a movement.

Like all of HASTAC, #FutureEd is open, free, user-generated. One of our mottos is that difference isn’t our deficit; it’s our operating system. Anyone can go to the website and add a course, a webinar, an onsite or online public event, and be part of our listservs to receive newsletters and updates of events.

In January, HASTAC will post three different wikis: one for crowdsourcing bibliography (books, articles, videos, url’s); another for learning methods, teaching, and pedagogy; and yet another for models of successful institutional change.

Not everyone will like every idea. But we hope everyone will find something that inspires creative thinking.

We are not advocating any one model. For example...

- Professor Steven Berg of Schoolcraft, a community college in Livonia, Michigan, is leading the Ocelot Scholars #FutureEd project.

- In Europe, the Coimbra Group (GC) Association of 40 European Universities is hosting a video seminar series "eLearning and eTechnology Taskforce."

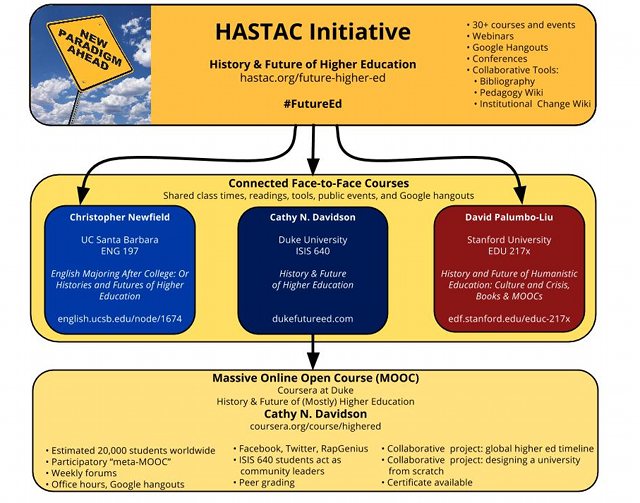

- And I’m involved in a complicated range of experiments (see infographic below) both in a graduate class at Duke University and in partnering with Profs Christopher Newfield at University of California Santa Barbara and David Palumbo-Liu at Stanford. We are teaching at the same time, creating listservs for our students to communicate across institutions, teaching some of the same texts, and arranging Google Hangouts for our students and a larger public.

My onsite students will also be learning by doing, acting as “community wranglers” in the MOOC where, each week, they will participate in online and face-to-face dialogue about what they are reading, thinking, and making. They will also work in teams to “Design Higher Ed from Scratch,” coming up with four or five models of extremely diverse kinds of post-secondary learning, and disseminating those for feedback and amplification to the largest possible audience, including in the MOOC.

I don’t know if legislatures and VC’s will be rushing at us with open pocketbooks to fund our ideas, but I do know that students, parents, and the general public will welcome productive, thoughtful, reflective change on the part of dedicated educators and future-looking students.

With that sentiment in mind, I want to conclude by dispelling a myth of the so-called MOOC era.

It is commonplace for would-be educational reformers to say higher education hasn’t changed in 2000 years, since the Greek Academy. That’s wrong.

Notably, the period between roughly 1865 and 1925 saw a crisis in confidence around the purpose of higher education for the industrial world, and, in response, educators came up with many of the innovations that we now think of as the apparatus of higher education: electives, requirements, majors and minors, semesters, divisions, land grant universities, professional schools, graduate schools, correspondence schools, IQ tests, multiple choice tests, grades, class ranking, school rankings, productivity metrics, modern statistical analysis, tenure, and much more.

Transforming education for our age is less about knocking Socrates off his pedestal than knocking a bit of the stuffing out of Frederick Winslow Taylor and his ideas of scientific labor management—and its learning equivalents.

If ever Taylorism was a good model for learning (and, personally, I have my doubts), it is certainly not a very good way to train independent, connected ways of thinking in an era when anyone with access to the Internet can communicate anything, instantaneously, to anyone else with access to the Internet.

That is a new human capacity.

We need to rethinking the best forms of learning for this tremendous opportunity and enormous responsibility. That’s what #FutureEd is about. We hope you’ll join us!

Cathy N. Davidson is the John Hope Franklin Humanities Institute Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies and Ruth F. DeVarney Professor of English at Duke University. She is also Co-Director, PhD Lab in Digital Knowledge at Duke and Co-Founder, HASTAC (hastac.org).