You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

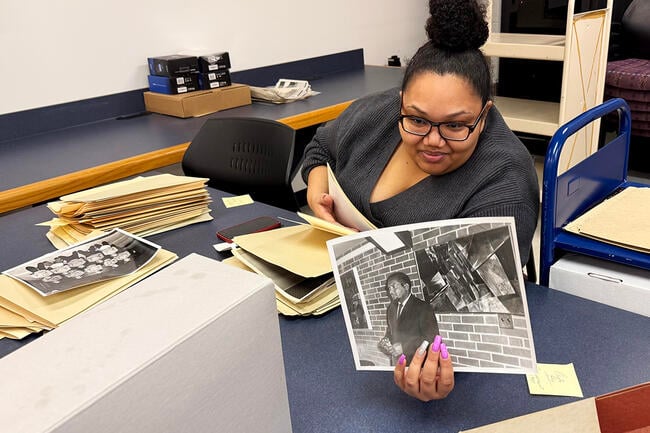

Lincoln University in Pennsylvania is digitizing its photos and documents with the help of Getty Images and Ancestry.

Cassandra Illidge

A group of Claflin University students were perusing old campus photos when one image caught a student’s eye—it was a picture of his grandmother from her college days. He knew they attended the same historically Black university in South Carolina, but he had never seen a picture of her in her younger years.

For Cassandra Illidge, vice president of global partnerships and executive director of the HBCU Grants Program at Getty Images, such moments both drive and affirm the company’s expanding work with HBCUs to preserve photos, documents and records in partnership with the genealogy website Ancestry.

Identifying his grandmother gave that student “a deeper connection with that institution, with the history and that legacy,” Illidge said, “and that’s what we’re hoping everyone will enjoy with this relationship and this partnership.”

Funded by Getty Images’ HBCU Grants Program, which started in 2021 with four institutions, the new partnership aims to digitize HBCU archival materials ranging from photos to student newspapers to course catalogs. Getty and Ancestry are working with 10 HBCUs—and counting—to create searchable digital archives for each institution, accessible to students and staff on Ancestry’s website. HBCUs maintain full copyright ownership of all their materials, and any money made from licensing the photos goes back into the digitization project. Meanwhile, students on each campus, who can receive stipends provided by the restaurant chain Denny’s, help to identify documents and photos to preserve and digitize them using scanners donated by Epson.

The companies are also preserving current documents and records for students and alumni of the future.

“You’ll see campus queens from the1950s and campus queens from 2025,” Illidge said, referencing a time-honored HBCU tradition of crowning royal courts.

The project is an expansion of Getty Images’ ongoing work to preserve HBCU photography through its HBCU Grants Program. Illidge had long wanted to put HBCUs’ archival materials on Getty but found the institutions didn’t necessarily have the resources or technology to digitize their rich photography collections. The grant supported that work, but she soon realized that HBCUs needed resources to immortalize pieces of their histories beyond imagery, and Ancestry seemed like the right partner.

“There were so many stories that needed to be told,” she said. “There’s so much material that still needs to be uncovered for research purposes, for licensing, for storytelling.”

‘History Coming to Life’

Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, the first degree-granting HBCU in the country, was also the first to participate in the joint project. So far, about 700 of its archival photos have been digitized, with plans to add documents and records, dating back to its charter in 1854.

Harry Stinson III, interim vice president of institutional advancement at Lincoln and the executive director of the university’s foundation, said prior to 1910, U.S. Census records for African Americans weren’t well-kept, but Lincoln has “impeccable records” of its students dating back to 11 years before Emancipation. So, the university is now digging up documents and information about people’s ancestors they’d be hard-pressed to find elsewhere, and making those materials available to students, employees and Ancestry users outside of campus.

Lincoln University students and staff edit an edition of the campus newspaper, The Lincolnian, in 1954.

Lincoln University/Getty Images

Stinson hopes people use Lincoln’s digital archive to “find their own story of themselves. That’s what college is for,” he said. The archive can “help you connect the dots of your family and your history, your heritage. We want people to learn more about themselves.”

Meanwhile, students working on the project get to try their hand at archival work, photography restoration and other skills and learn about potential career paths.

Already, people are uncovering their families’ stories. When Maryland governor Wes Moore came to campus recently to speak at commencement, for example, he was able to see his grandfather’s writing in Lincoln’s student newspaper, as well as his grades and photos.

Stinson has also been excited to uncover photos of well-known Lincoln alumni and visitors to campus, including U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall studying and actor Paul Robeson, whose father and grandfather attended Lincoln, coaching football.

“It’s just seeing history coming to life,” he said.

The Political Moment

The project comes at a time when preserving and sharing Black history, and American history more broadly, has become a contentious political issue.

President Donald Trump signed an executive order in March, titled “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” which took issue with portrayals of the country as “inherently racist, sexist, oppressive, or otherwise irredeemably flawed.” The order accuses the Smithsonian museums of adopting a “divisive, race-centered ideology” and calls to “remove improper ideology” from these institutions—including the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

A January executive order aimed at K-12 schools also demanded children be provided a “patriotic education” and included guidelines for the teaching of history. Further, the administration recently fired the librarian of Congress, in part for doing “concerning things” in “pursuit of DEI,” according to White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt.

Meanwhile, many companies and academic institutions have backed off initiatives or projects focused on Black communities and perspectives amid a broader federal backlash to any initiatives officials perceive as DEI-related.

Lincoln University professor Willie Williams teaches students, 1970.

Lincoln University/Getty Images

Some civil rights groups have adopted a fighting stance against federal attempts to dictate how history is remembered and taught. For example, a coalition of groups, including the African American Policy Forum, the National Urban League and the National Action Network, signed an “affirmation in defense of Black history, texts and art” and held a demonstration earlier this month in support of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“We must protect our history not just in books, schools, libraries, and universities, but also in museums, memorials, and remembrances that are sites of our national memory,” the affirmation reads. “Racial inequality remains real; if we are not able to understand it, tell its history, and honor those who have risked everything to solve it, then we lose our capacity to carry the legacy, brilliance and resilience of these freedom fighters in our lives and to future generations.”

Stinson said it feels “fulfilling” to collect and digitize Lincoln’s history right now, and it’s “ideal timing.” He believes the documents and photos being preserved through Getty Images and Ancestry are of value to all Americans. He highlighted the fact that Thurgood Marshall and other Lincoln alumni are historical figures not just for Black Americans but for the country at large.

“We’re not just talking about Black history, we’re talking about American history,” he said. The images and records collected show “what African Americans have been able to achieve when given the space and the opportunity to learn and to thrive.”

Illidge emphasized that Getty Images is working to “preserve history … Black history, all history.”

“This amazing material that’s coming from HBCUs is just another line of history that we can share with the world,” she said. “Regardless of administration, or any other changes, we’re not changing our goals and mission.”

(This story has been updated to correct the sport Robeson coached.)