You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

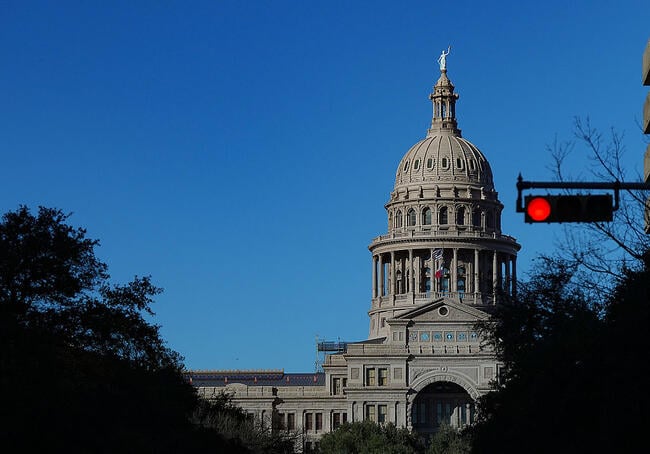

The Texas State Legislature passed Senate Bill 37 on May 31. It awaits the governor’s signature.

Houston Chronicle/Hearst Newspapers/Contributor/Getty Images

Texas public college and university presidents will be able to take control of their faculty governing bodies if Gov. Greg Abbott signs a bill now before him.

“Shared governance structures may not be used to obstruct, delay, or undermine necessary institutional reforms or serve as a mechanism for advancing ideological or political agendas,” says Senate Bill 37, which the Republican-dominated State Legislature passed May 31. Multiple states have considered GOP bills targeting shared governance, but SB 37 is a sweeping example.

It says that “only the governing board of an institution of higher education may establish a faculty council or senate.”

“The board of regents has to decide whether or not there will even be one, that’s problem No. 1,” said Brian Evans, president of the Texas American Association of University Professors–American Federation of Teachers Conference.

If a college or university board decides to keep a faculty governing body, the institution’s president gets to prescribe how it conducts meetings. The president also gets to pick the “presiding officer, associate presiding officer, and secretary.”

In addition, unless the college or university’s board decides otherwise, faculty senates and councils must shrink to no more than 60 members.

Those remaining 60 would have to include at least two representatives from each of the colleges and schools that comprise the institution—including what the bill describes vaguely as “one member appointed by the president or chief executive officer of the institution” and the rest elected by the faculty of the particular school or college. This could mean that half of a faculty senate or council would be chosen by the president if an institution’s board doesn’t grant exemptions from these requirements.

Andrew Klein, speaker of the Texas A&M University Faculty Senate, said the biggest concern among his 122 senators is the 60-senator limit, which will take effect unless the Texas A&M System Board of Regents grants an exemption. Klein questioned how a senate that small could represent 4,300 faculty across the university, and how a requirement for at least two representatives per college or school would provide fair representation when the College of Arts and Sciences has over 800 faculty, compared to a number in the low double-digits at the School of Engineering Medicine.

“With 60 people, that’s not enough different viewpoints that can be brought to bear on questions, given our complexity,” Klein said.

In another blow to faculty control of their own governance bodies, SB 37 establishes term limits for faculty senate and council members—and allows presidential appointees to serve longer than the elected members. The presidential appointees would get to serve six consecutive years before having to take two off, while the elected members could only serve two years before the mandatory two-year break.

A faculty senate or council member could also have their seat stripped at any time; the bill says the provost can recommend to the president that members be “immediately removed” for failing to attend meetings or conduct their “responsibilities within the council’s or senate’s parameters” or for “similar misconduct.”

“It’s no longer an elected faculty voice,” Evans said. “It’s controlled by the administration.”

The bill still says that faculty senates or councils can hold votes of no confidence in administrators. But its language elsewhere stresses that faculty governance has no final say over anything.

“A faculty council or senate is advisory only and may not be delegated the final decision-making authority on any matter,” the bill says. (The faculty senate leaders at Texas A&M University at College Station and the University of Houston said their bodies are already advisory.)

Ultimately, the bill defines shared governance in a way that stresses the supremacy of college and university boards, which are composed of gubernatorial appointees who are confirmed by the state Senate.

“The governing board of the institution exercises ultimate authority and responsibility for institutional oversight, financial stewardship, and policy implementation, while allowing for appropriate consultation with faculty, administrators, and other stakeholders on matters related to academic policy and institutional operations,” the bill says. “The principle of shared governance may not be construed to diminish the authority of the governing board to make final decisions in the best interest of the institution, students, and taxpayers.”

In addition to overhauling faculty senates, SB 37 would require the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board to establish an advisory committee that would review general education requirements statewide and be responsible for considering methods for “condensing the number of general education curriculum courses required.” Furthermore, colleges and universities would be required to review minors and certificate programs every five years “to identify programs with low enrollment that may require consolidation or elimination,” according to the bill.

Dan Price, president-elect of the University of Houston Faculty Senate, said this goes “hand in hand” with the Legislature’s efforts to diminish faculty senate power.

“The ways in which the humanities could be really transformed, I think that’s not well considered,” he said.

‘Woke College Professors’

Abbott has indicated he wants faculty power reduced.

Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

Will Abbott, a Republican, sign this into law? His press secretary, Andrew Mahaleris, didn’t directly answer in an email to Inside Higher Ed.

“More than 1,000 pieces of legislation have been sent to Governor Abbott’s desk and he is closely reviewing them all,” he wrote.

But Mahaleris’s email indicated that the governor is strongly in favor of reducing faculty power.

“Governor Abbott was clear in his State of the State address: Woke college professors have too much influence over who is hired to educate our kids,” Mahaleris wrote. “Texas needs legislation that prohibits professors from having any say over employment decisions.”

Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, who leads the Texas Senate, also touted the bill. Upon the Legislature’s adjournment, he issued a statement calling it the “Senate’s most conservative and successful legislative session.” He attributed that in part to SB 37, which he said was about “reforming liberal faculty control over universities.”

The author of the introduced version of the bill, Republican senator Brandon Creighton, didn’t respond to Inside Higher Ed’s requests for an interview or to written questions last week.

For faculty, Abbott’s decision on the bill is merely the first step. If he signs it, they’ll still be looking to their institutions’ boards to decide whether, and how, their faculty senates and councils can continue to operate.

“I really don’t have a good idea of what we’re going to look like next year,” said Klein, the speaker of the Texas A&M University Faculty Senate.

Price, the University of Houston Faculty Senate president-elect, said he thinks the bill is partly “based on a misunderstanding of what faculty senates had been doing. It assumed that faculty senates were run much more like unions.” He said there was “a lot of animosity toward faculty senates.”

“We’ve got work to do to make sure that the public sees the value of faculty,” Price said, along with the values of open inquiry and “faculty having real and influential voices and choice of curriculum.”