You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

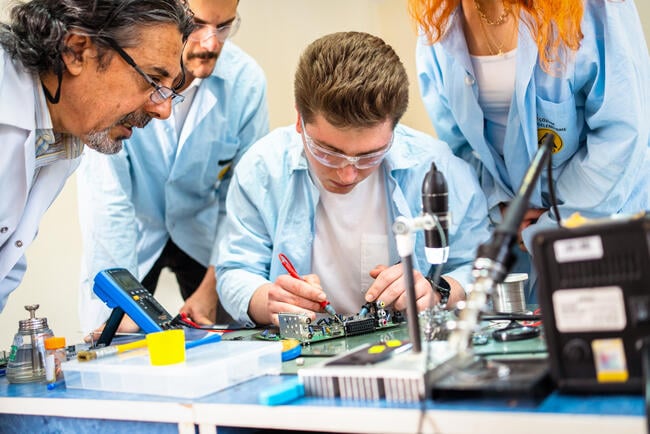

Funding for career and technical education programs could come under the auspices of the Department of Labor.

Phynart Studio/E+/Getty Images

Proponents of career and technical education programs and Democratic lawmakers are wringing their hands over the Department of Education’s plans to offload the funding and administration of CTE programs to the Department of Labor.

They worry the plan, if enacted, would be a nail in the coffin of the Education Department, sow confusion and diminish the quality of these secondary and postsecondary career-prep programs.

News of an interagency agreement emerged earlier this month when the government filed a status report in court to show its compliance with an injunction preventing the administration from dismantling the Education Department. The agreement, blocked by that order, would move the administration of CTE program funding, under the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act and the Adult Education and Family Literacy Act, to the Department of Labor. Department officials quietly signed the agreement May 21.

Madi Biedermann, deputy assistant secretary for communication at ED, said in a statement to Inside Higher Ed that the goal is to help the two agencies “better coordinate and deliver on workforce development programs and strengthen federal support for our nation’s workforce, a top priority of the Trump Administration.”

“This is one of many existing agreements ED has with other agencies to collaborate on services for the American people,” she said. “As acknowledged in the status report, ED has paused implementing this [interagency agreement] while we seek relief from the district judge’s preliminary injunction.” (The government has appealed to the Supreme Court.)

The agreement claims the move would lead to “process improvements,” streamline data collection on program outcomes and better align CTE programs with the Department of Labor’s short-term job training programs, funded under the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act. The agreement also cites President Donald Trump’s March executive order that called for returning “authority over education to the States and local communities.” The same order called for the Education Department’s closure.

Critics strongly oppose the plan.

Democrats in Congress insist, first and foremost, that the Education Department doesn’t have the authority to make such a change.

A group of lawmakers emphasized in a recent letter to Education Secretary Linda McMahon, that Congress authorized the Education Department to administer CTE program funds—not the Department of Labor.

“Respectfully, federal agencies are not interchangeable entities that simply hand out money to states and localities,” they wrote. “Congress recognizes the expertise that specific agencies provide and very deliberately decides which agency to vest authority with when passing laws.”

CTE proponents nonetheless expect the department to press ahead with the plan in the long run and worry about how a new department could change the programs.

Fears for the Future

Some CTE advocates worry the agreement would complicate these programs and create bureaucratic mazes for grant recipients to navigate. Over all, about $1.4 billion annually is at stake for K–12 schools, colleges and states, which supports roughly 11 million students across the country.

The agreement, as written, maintains the Education Department’s control over some aspects of CTE programs, such as audit resolution processes, but it puts other responsibilities and the administration of funds under the auspices of the Department of Labor.

Alisha Hyslop, policy, research and content director at the Association for Career and Technical Education, said that approach is a recipe for confusion.

“Even reading through the details that are included, we have a lot of questions,” Hyslop said. “We don’t really understand how it would work and how the two agencies would work together … Instead of creating efficiencies, which I know is the administration’s goal, this seems to make it even more complicated for states and locals that are implementing Perkins.”

Some CTE proponents also fear moving Perkins funding to the Labor Department could undermine the programs’ academic rigor.

The programs are intended to arm students, as young as middle school through college, with academic and technical, career-focused skills and generally involve a sequence of courses, whereas the Department of Labor’s short-term job training programs narrowly focus on workforce development for adults in specific fields, Hyslop said.

“It’s a different program model,” she said. “CTE really starts with career exploration and then builds and bridges students for lifelong learning and careers.” She doesn’t want their focus to shift to “short-term workforce outcomes at the expense of long-term educational development.” She worries the agreement would “disconnect CTE programs from the broader education system.”

The Bigger Picture

Braden Goetz, senior policy adviser in the Center on Education and Labor at New America, a left-leaning think tank, fears the agreement could result in a return to old-school secondary vocational programming that put some students on tracks to specific careers and others on track for college. The Department of Labor’s job-training programs “have an important purpose helping people that are out of work find a job quickly,” but he doesn’t want to see CTE programs become just another version of them.

“For young people, it might narrow their horizons,” he said. “I think that’s where the program would be headed if it was at the Department of Labor.”

For him, the agreement also has greater meaning—it’s an initial step in the Education Department’s plans to offload its responsibilities and ultimately diminish itself.

He expects to see the department come out with other plans to jettison programs, such as moving the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act to the Department of Health and Human Services.

“It’s just the beginning of dismantling the department,” he said.

Mark Schneider, a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank, believes concerns about CTE programs losing their character under the Department of Labor are overblown, given CTE programs have both an education and workforce development function.

“What do we want from our education system?” Schneider said. “We want people who are good citizens and people who are good workers, that are able to get into the labor market, that are able to do good work, that are able to have family-sustaining wages … CTE is one of the major ways that we have, hopefully—to the extent to which we get it right—to produce the workers that we need, that the nation needs.”

For him, the bigger question is not who administers the funding but “what’s the goal of our education and our workforce training? And let’s figure out what’s the best way to do it.”

He isn’t a fan of the administration’s “piecemeal” approach of “we’ll take this and move it here and move it there,” but he said he sees the upheaval as an opportunity for the federal government to break with old norms for how education programs are run and studied.

For example, his sights are set on reforms to the National Center for Education Statistics, which he believes needs modernizing and might benefit from consolidating with the Bureau of Labor Statistics and other federal statistical agencies. He hopes the preliminary injunctions give the administration a moment to “pause” and that it “takes the time to figure out what we really need.”

“Given all the disruption, everything should be up for grabs,” he said. “But what do we want? What do we really want going forward?”