You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

ISTOCK.COM/Darren415

People from neighborhoods that are majority Black or Hispanic are less likely to attend college, and when they do, they borrow more and default on student loans more, according to a report from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

These findings, among others, are part of the series "Introduction to Heterogeneity Series III: Credit Market Outcomes," which explores racial differences in outcomes for education, housing and health care.

"These are critical social issues that long predate COVID-19, but it’s clear that the implications of each have been made starker by the coronavirus," said Andrew Haughwout, senior vice president at the New York Fed, during a presentation on the reports.

The researchers analyzed differences in college attendance rates, student debt and defaults by racially segregated neighborhoods, and how tuition subsidies affect other debt and consumption habits.

For the former issue, researchers used data from the New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel and the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, as well as U.S. Census Bureau data to classify ZIP Codes as majority white, Black or Hispanic.

"We can see that there are considerable differences … when we’re looking at the racial composition of neighborhoods," said Rajashri Chakrabarti, a senior economist at the New York Fed.

The analysis found that people from majority white ZIP Codes attend college at the highest rates, followed by those from majority Black ones. Those from majority white ZIP Codes attended four-year colleges at higher rates compared to the other groups. People in the majority Hispanic ZIP Codes had the highest attendance rates for two-year colleges.

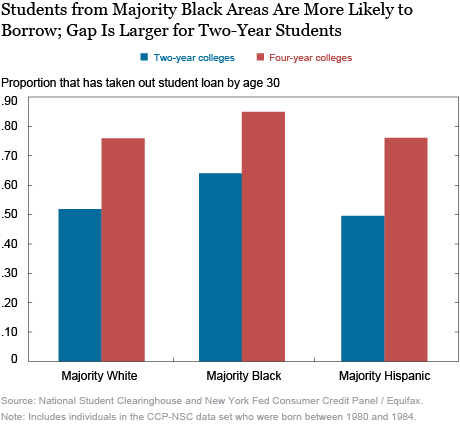

Similarly, for student loans, people from majority Black neighborhoods who attended college are more likely to take on student loans than those from majority white or Hispanic areas. Those from majority Black areas were 9 percent more likely to have a student loan by age 30 than the other groups.

Similarly, for student loans, people from majority Black neighborhoods who attended college are more likely to take on student loans than those from majority white or Hispanic areas. Those from majority Black areas were 9 percent more likely to have a student loan by age 30 than the other groups.

Those from the majority white or Hispanic areas had the same propensity to have student debt, and those who attended four-year colleges carried similar debt balances by age 30, according to the report. Those in majority Hispanic neighborhoods who attended two-year colleges borrowed at slightly lower rates than their white counterparts and had lower balances by age 30.

Borrowers in majority Black areas carried higher debt balances than the other groups. Notably, those who attended two-year colleges had 45 percent higher balances at age 30 than their Hispanic counterparts, compared to 23 percent greater balances for attendees of four-year colleges.

When looking at student loan default rates, researchers found that borrowers who attended two-year colleges default on their loans almost 50 percent more than those who attended four-year colleges, across all racial neighborhoods, by age 30. Even though those who attend two-year colleges are less likely to borrow, the "debt they take on is riskier," the report said. This is probably due to differences in labor outcomes between four-year and two-year colleges, Chakrabarti said.

Over all, borrowers in majority Black or Hispanic ZIP Codes are more likely to default on this debt by age 30. Borrowers from majority Black areas who attended two-year colleges defaulted at 1.9 times the rate of those in majority white areas. Those in majority Hispanic areas defaulted 1.7 times as often as their white counterparts.

"These disparities in debt and default patterns are stark and it is important to better understand the underlying reasons for these differences -- a challenge we will take on in future work," the report said.

The second analysis related to education compared debt and consumption outcomes of students who were eligible for tuition subsidies because of their age and home state with those weren't eligible for aid because their home state did not implement such a program when they attended college.

For students who were eligible for the aid, researchers found an increase in short-term spending captured by credit card debt, though this effect disappears after students age past their early 20s. This implies that students substituted one form of debt (student loans) for another (credit cards), Chakrabarti said. This pattern is more pronounced for students from majority Black or Hispanic ZIP Codes.

There also was an effect on credit card delinquency. A student from the aid-eligible cohort was 1.8 percentage points more likely by age 25 to have been at least 90 days delinquent on their credit cards than a student who was not eligible for the aid.

Students eligible for aid were also one percentage point more likely to have bought a car with an auto loan, researchers found. This is especially prominent for students from majority Black or low-income areas.

Over all, researchers found that aid eligibility increases debt levels for students in their early 20s but reduces it later in life. The total debt burdens for those eligible for aid, including student, mortgage, credit card and other debts, decreased in their late 20s.